Cartoons for African children are frozen by a lack of funding and imagination

For a century, animated films have shaped the childhood memories of children all over the world. Children in Europe and North America, though, have had the privilege of recognizing themselves in these characters. This is why Disney princesses Jasmine, Mulan and Tiana were almost revolutionary for being Middle-Eastern, Chinese and African-American, respectively. Those characters just don’t exist for African children.

For a century, animated films have shaped the childhood memories of children all over the world. Children in Europe and North America, though, have had the privilege of recognizing themselves in these characters. This is why Disney princesses Jasmine, Mulan and Tiana were almost revolutionary for being Middle-Eastern, Chinese and African-American, respectively. Those characters just don’t exist for African children.

African animators often find themselves trapped between a paucity of international imagination and a lack of funding. Disney’s 1994 The Lion King remains the archetype of what an animated Africa—a mix of Swahili phrases, superficial spirituality and a sprawling savannah. In the more than two decades since the film’s release, few alternate narratives have been created for African children.

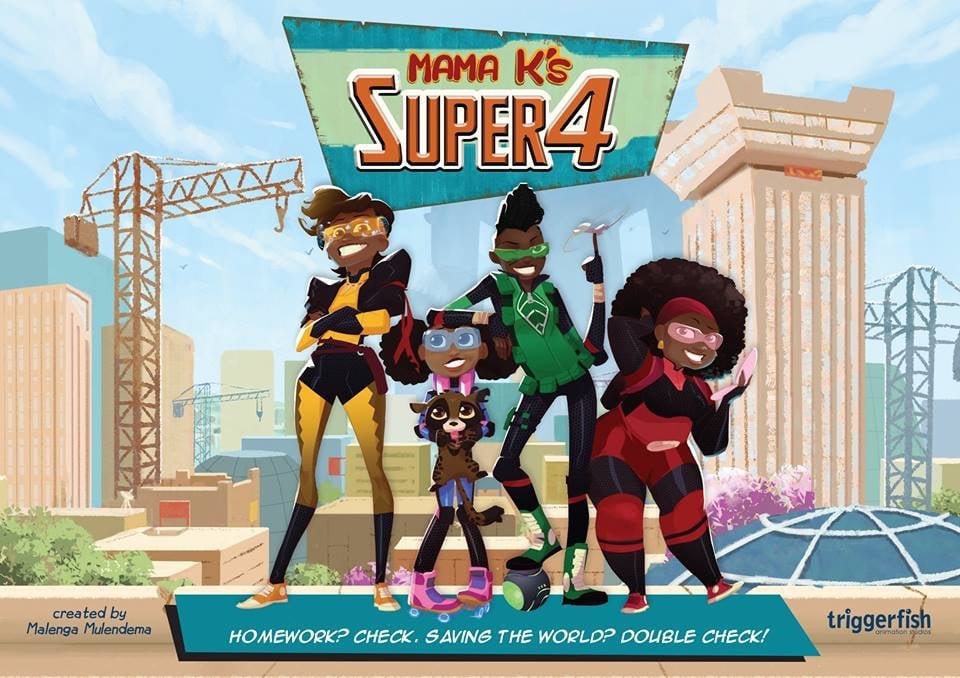

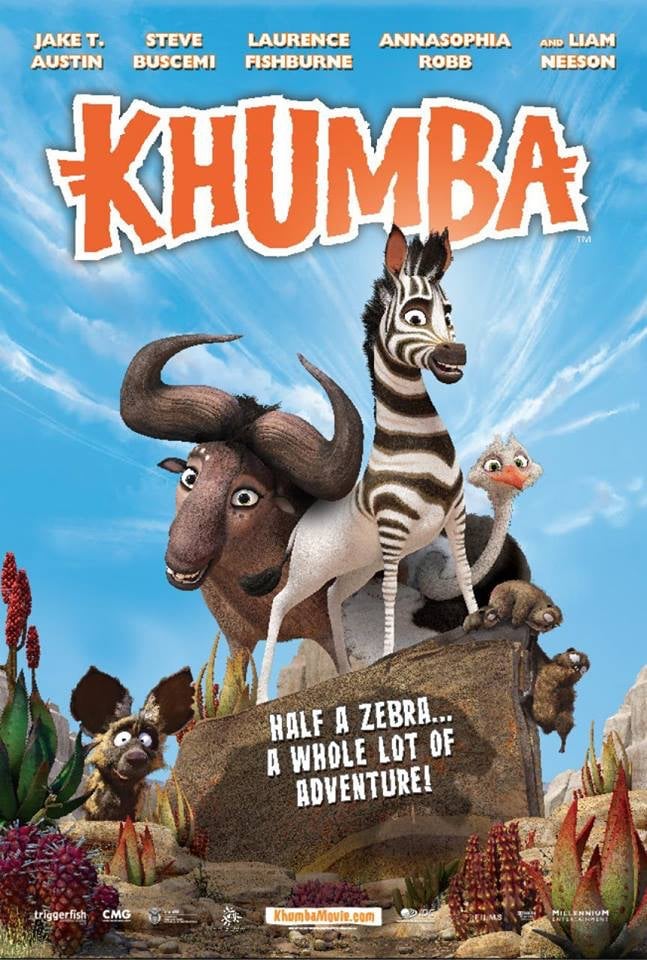

With Khumba, a half-white zebra, South African animator Stuart Forrest and his team leaned into the familiarity of animal fables, but tried to add more complexity to his characters, while creating a very specific landscape of South Africa’s semi-arid Karoo landscape. The 2013 film featured the voices of Steve Buscemi, Liam Neeson and Laurence Fishburne and directed by Anthony Silverston, was lauded by critics and broke records for a South Africa film, particularly over one million ticket sales in China.

To replicate Khumba’s success would require redesigning the landscape of the industry, not just on screen, says Forrest. The producer is painfully aware of the lack of diversity in the South African animation industry, dominated by white males from a similar cultural background. Since South Africa is the continent’s animation leader, even stories set and produced in Africa may not adequately represent African children, he explains.

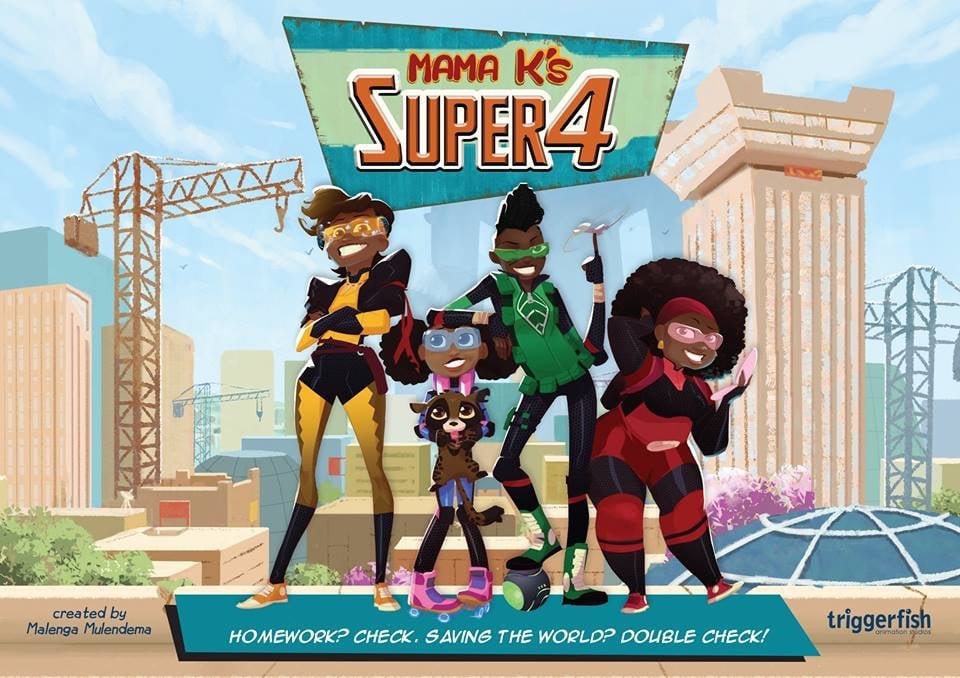

In collaboration with the South African government’s department of trade and industry and Disney Studios, Triggerfish is running Story Lab, which invites scriptwriters from around the continent and supports them in beginning to tell their stories. So far, they’ve uncovered gems like Mama K’s Super 4, a group of Zambian superheroes who do their homework and save the world—often by catching a taxi.

Making great television is cheaper than a feature film, and it will allow investors to realize that the continent has the eyeballs to sustain an industry here. And yet, as Forrest and other animators have found that the existing business model has been unable to imagine much profit from Africa.

“Filmmakers do not look at Africa as a market and aren’t particularly interested in the fact that there are 400 million children in Africa,” said Forrest, whose company makes 1% of their profits from the continent they draw from. “It’s the future and I don’t think anyone is making content for those children.”

“The business of animation is very challenging,” said Tim Argall, founder of Johannesburg-based BugBox animation studios. Argall’s work is seen on well-known South African advertisements, but his ambitions lie with creating feature-length children’s films and syndicated series.

Musi and Cuckoo is the edutainment story of a jolly hippopotamus and a whacky chicken aimed at pre-schoolers, but the series has taught Argall some hard lessons about the animation industry. South Africa’s public broadcaster is in disarray and cannot support initiatives like this, as public television does in other countries. For paid television, it’s cheaper to buy an already completed, well-known brand.

Argall got support from an independent broadcaster, enough to encourage confidence in other investors and distributors but not enough to cover the high costs of creating an animated series. One broadcaster thought it was too African, another thought it wasn’t African enough and so the series is stuck, said Argall. He points to France, where the government realized the cultural significance of animation, investing early to create a profitable alternative to Disney and Pixar.

The creators of the SupaStrikas series found a successful model in the football world in which their series is based. SuperStrikas follows an ethnically diverse football team around a globally cosmopolitan Super League, as they learn lessons on teamwork and fair play. Like a real-world football team, the players have sponsorships, complete with logos on their jerseys.

“Like any great football team; ours got sponsors,” said producer Richard Morgan-Grenville. “We put the main advertiser on the jersey and supporting sponsors went all over the place.”

Seamless product placement around a talking hippo may be more difficult to achieve and so it’s up to animators to spark the imagination of investors and audiences, while also balancing the books.