African governments, not religion, are pushing their young people into extremism

Africans who didn’t sing the national anthem as a child are more likely to be recruited into violent extremist groups. Those living in the periphery of their country with less access to education and health services are more vulnerable, as are those with less involved parents. Exposure to state violence, not religious ideology, is a better predictor of radicalization.

Africans who didn’t sing the national anthem as a child are more likely to be recruited into violent extremist groups. Those living in the periphery of their country with less access to education and health services are more vulnerable, as are those with less involved parents. Exposure to state violence, not religious ideology, is a better predictor of radicalization.

These are some of the findings of one of the most comprehensive studies, released this week, into why young Africans across the continent join militant groups like Boko Haram, al Shabaab, or al Qaida. The two- year study by the UNDP, Journey to Extremism, is based on interviews of more than 500 voluntary and forced recruits of extremist groups in Kenya, Somalia, Nigeria, Sudan, and to a lesser extent, Cameroon and Niger. The interviews were done mostly in detention centers.

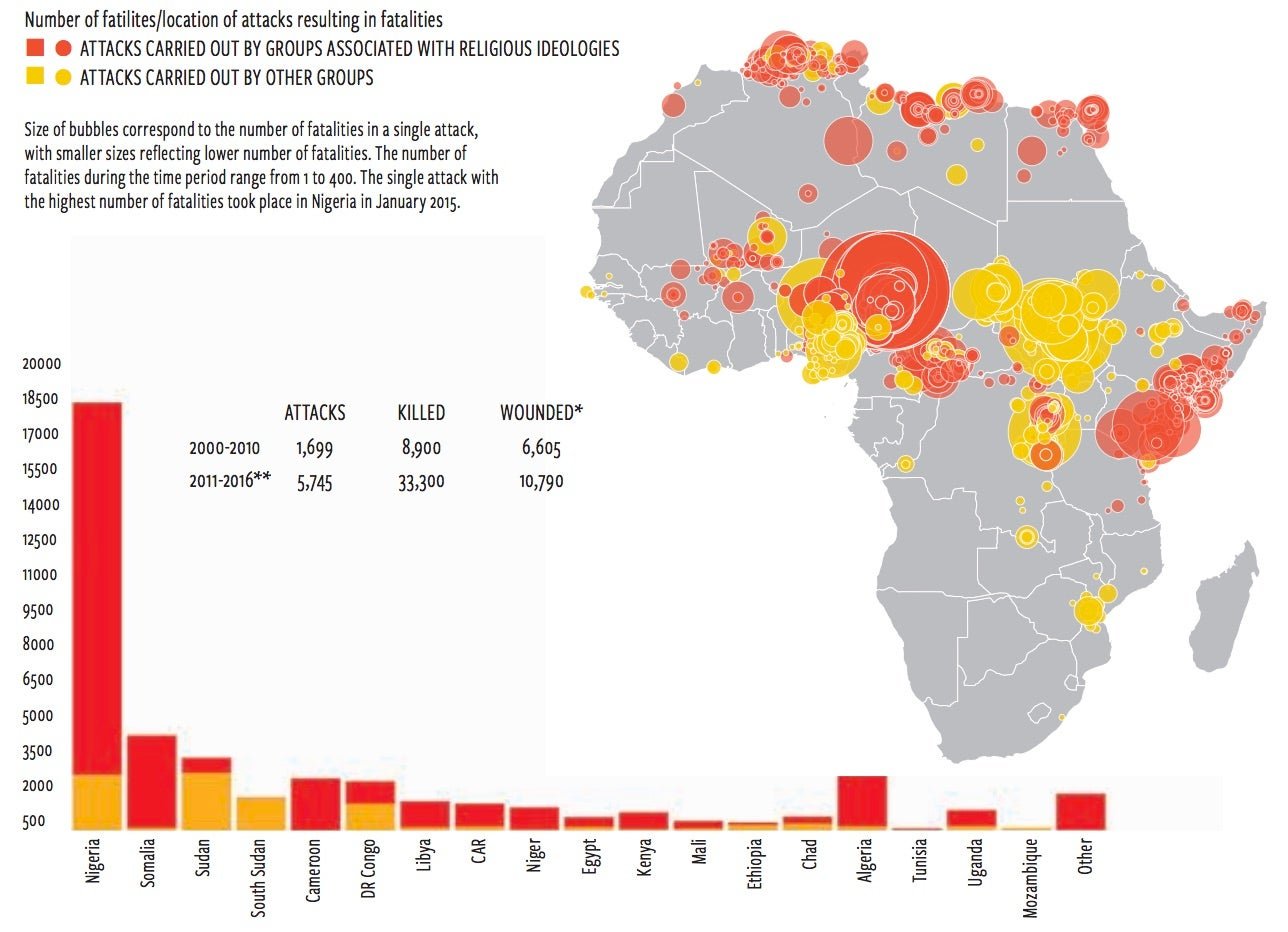

Sub-saharan Africa has the second highest number of deaths caused by violent extremism after the Middle East and North Africa, according to 2015 data from the Global Terrorism Index. Yet terrorism in Africa is among the least studied. A recent analysis of 3,000 peer-reviewed articles on violent extremism found that Africa and Southeast Asia were vastly underrepresented, based on a ratio of academic mentions to number of deaths caused by extremists. Of the 10 most under-referenced countries four were (pdf) in sub-Saharan Africa.

The most conclusive finding from the UNDP study might not be the most surprising one: state abuse and marginalization, not religion, are the most important factors in the radicalization process. The study found that in fact six years of religious schooling lowered the likelihood of an individual joining an extremist group by a third.

But it does show the extent to which governments are creating or worsening their own security situations. In addition to looking at unemployment, education, family circumstances, and religion, researchers asked former militants what motivated them to take the step to join an extremist organization. In 71% of cases, the respondents said that government force—either the killing or arrest of a family member or friend—was a tipping point for them.

“Paradoxically, state action appears to be the primary factor finally pushing individuals into violent extremism in Africa,” the researchers concluded.

It’s not just state violence pushing young Africans to radicalism; most respondents were between the ages of 17 and 26. Lack of civic engagement and identification with one’s country were other common traits among voluntary recruits. All other things constant, a respondent who sang the national anthem as a child was between 4% and 36% less likely to join a militant organization, according to the study.

The most surprising finding of the study is that despite this widespread government disaffection, the most common emotion recruits reported when joining extremist organizations was not anger or vengeance. (Those came in at third and fourth place.) ”Hope or excitement is recorded as the most common emotion when joining, perhaps reflecting the urge to transform otherwise impoverished and frustrating circumstances.”