An activist set fire to a CFA note and reignited a debate on France’s hold on Francophone Africa

A divisive decision by an activist to set a CFA note on fire in Senegal has reignited a debate on the common currency and the influence France still holds over francophone Africa.

A divisive decision by an activist to set a CFA note on fire in Senegal has reignited a debate on the common currency and the influence France still holds over francophone Africa.

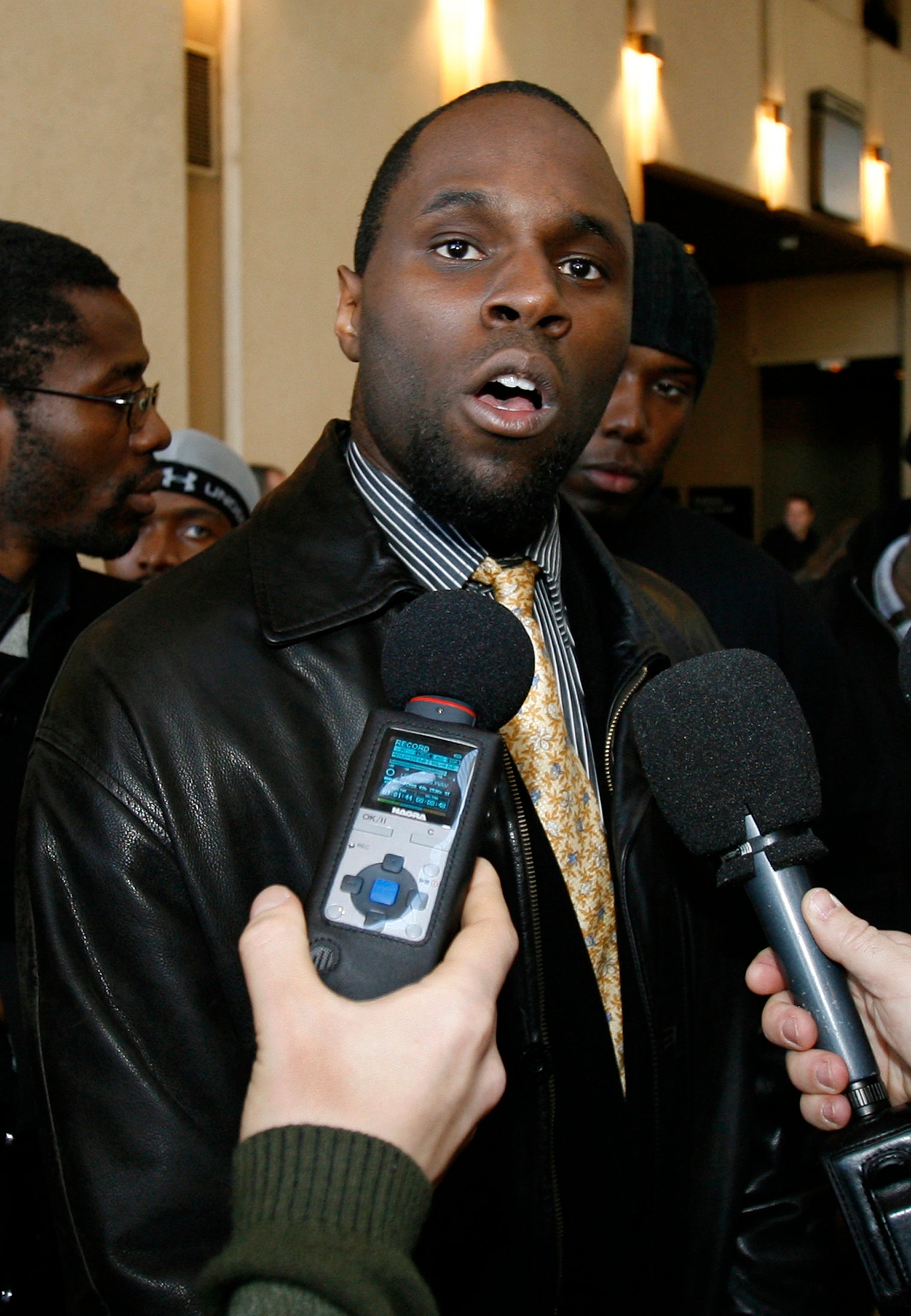

Kemy Seba set fire to a 5,000 CFA note (equivalent to $9.20) on Aug. 19, in protest over “Francafrique”—France’s continued political and economic influence over its former African colonies. Seba was arrested after a complaint by the Central Bank of West African States, which prints the notes. The West African CFA is the currency of Senegal and seven of other nations.

The currency remains pegged to the euro and governed by treaties with France. The currency is managed by two regional bodies (pdf), the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). The Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), manages the Central African CFA for currencies of oil producers like Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon and three other central African nations. In the Comoros, the CFA is known as the Comorian Franc.

Burning the CFA is a criminal offence, and Seba stood trial along with the man who handed him the lighter. But the court acquitted acquitted him on Aug. 31, reportedly on technicality—Senegal’s law punishes the destruction of multiple CFA notes, but not one.

Still, Senegal’s interior ministry deemed Seba’s presence in the country “a serious threat to public order” and expelled him on Sept. 7. Back in Paris and undeterred, Seba is planning (link in French) an anti-CFA rally in Paris on September 16. Senegal’s response has raised questions about freedom of expression in the country, nearly as many as Seba’s own political motivation.

Born in France to Beninese parents, 35-year-old Stellio Gilles Robert Capo Chichi has made a life of opposing France’s neocolonial ambitions. Dubbed the French Farrakhan (link in French), Seba founded the Kemite party, based on Black Nationalism and ideas of ancient Egypt but overshadowed by anti-Semitism, which eventually led to the “tribe’s” banning. Seba has since reinvented himself as a Pan-African activist and anti-colonialist.

Irrespective of his political background, setting fire to a single note worth about 7 euros, or $9, has forced many to question the colonial roots of the shared currency. One protestor compared seeing the note go up in flames to the moment when Nelson Mandela set is apartheid-era passbook on fire in 1960. On social media, some have hailed Seba while others have questioned his political motivations.

“While remaining doubtful about the relevance of the decision to expel this brother, I would like to say that I am equally shocked to see that our currency remains of colonial inspiration,” wrote one Facebook-user based in Douala. For others, the protest requires a different strategy, turning to technology instead flames.

“For decades, Africans have been fighting to change the governance of the francophone zone. Some have died,” wrote academic Alain Nkoyock. “Since the crypto-currencies (Bitcoin, Monero, Cash, or Dash) and the related technologies around them are about to upset the financial sector, why not invest all our last efforts to bypass the CFA?”

West Africa seems unwilling to let go of the shared currency, even launching a digital version, the eCFA. The CFA has its roots in the colonial era when France chose to print a single currency (pdf) for its colonies rather than transport cash. With independence, the printing authority became the central banks of West and Central Africa, guided by policies from Paris.

France devalued the currency in 1994, bowing to pressure from the rest of Europe that its support was akin to a subsidy. Since then, little reform has taken place. The two economic regions are not quite integrated, yet their value to the euro is exactly the same. Interest rates are set by the European Central Bank and France dominates trade with CFA countries. On the plus side, inflation remains low and Guinea, the only francophone country that doesn’t use the shared currency, has struggled.

France’s influence over the economies of 14 African nations also has political repercussions, which many young francophone Africans have blamed their presidents for. Seba’s act of protest tapped into a debate that has already been simmering.