How to cope with the social pressures of a “Yoruba” party in Lagos

You don’t want to arrive too early. By chance you actually have an invitation card (and not the ordainment of word of mouth), if it says 2 pm., arriving at 4 pm. is trying too hard. As we say in Lagos, don’t fall your own hand or, better yet, don’t stain your own white.

You don’t want to arrive too early. By chance you actually have an invitation card (and not the ordainment of word of mouth), if it says 2 pm., arriving at 4 pm. is trying too hard. As we say in Lagos, don’t fall your own hand or, better yet, don’t stain your own white.

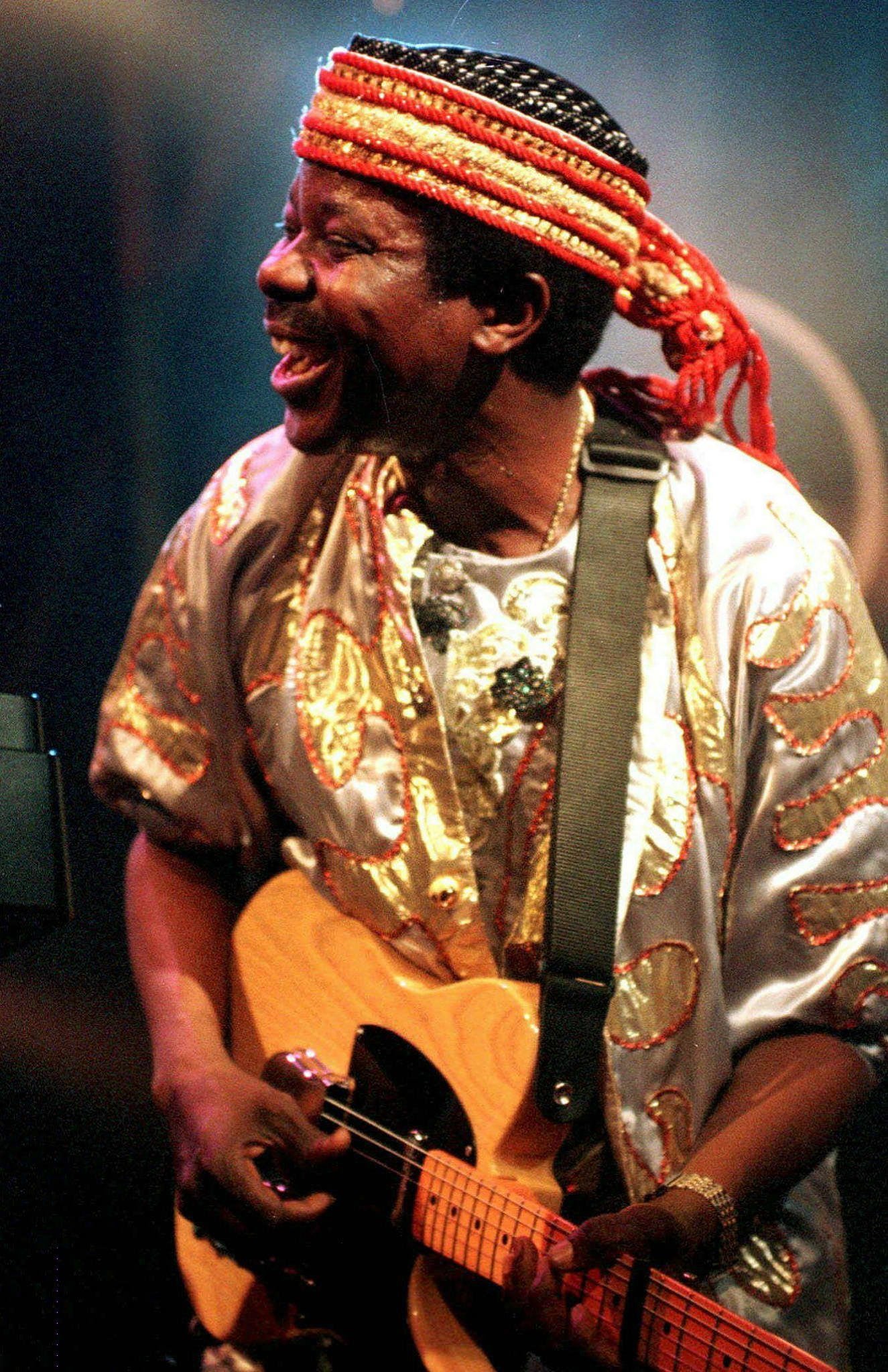

Indeed, Nigerian nights are dark and full of potential mishaps but getting to a party on time shouldn’t be one of them. So, be cool: stroll in at 6. At this time, the party should be nearing full swing: King Sunny Ade, Yinka Ayefele or Queen Ayo Balogun should already be on stage rocking as waiters zip through tables with trays of Jollof rice and the lesser foods, or baskets of drinks, dodging the bedazzled fingernails of eager Big Mummies.

Very likely an argument even erupts between a waiter and a Big Mummy: “Have I not been calling you?” “I’m sorry I didn’t see you Ma.” (Big Mistake.) “Do you even know who I am?” Basically, it’s not a Nigerian party if, at some point, someone doesn’t lose track of their identity.

In the southwest of Nigeria, where Lagos is located, Yoruba people are the majority ethnic group, population-wise. In Lagos, everything begins at a party and the interactions of history, geography and commerce, ensure that the megacity is the capital of not only Yoruba but also, increasingly, all Nigerian enjoyment. Yoruba or not, everyone is welcome—so long as you know the rules: respect the elders, dress up but don’t upstage the host unless you are or aspire to be mortal enemies.

Over the years, I’ve learnt the trick is to call a waiter aside the moment you enter the party. Hand him or her a crisp note—500 naira ($1.50) should do, 1,000 naira ($3) if someone is watching (as people, Nigerians may lose the race against appearances but not for want of trying)—point the waiter to your table and watch that table never run dry. You want to “buga”, which is another way of saying you want to inflate your presence until it becomes a self-emanating orb.

Here’s the thing, no Yoruba party, especially in Lagos, is ever about the hosts. Every party—from small, highly geared, rent-a-canopy neighborhood celebrations that spill onto streets and eventually drown them in debt, to million-naira fiestas housed in Chinese-developed hotel ballrooms where terms like recession are forbidden—is about the other guests. This is why, at their default, Yoruba parties are social status battlegrounds; each table a satin-draped station armed with side-eyes, damask, organza and brocade, handheld fans, fingers twirling car keys, and their phone No.2’s peeping from crocodile-skinned clutch bags and the grooves of their agbadas. Each table seems to be in a contest to see whose “house” will be the first to capitulate, cross over, “bend the knee”, and say hello, in our perpetual Game of Thrones.

These days, it is not uncommon to see a Big Daddy, his “buga” an iPad the size of a flat-screen TV. Nobody talks business at these parties. At most, people attend to display not how they made it but what they’ve made, “What the Lord has done,” and, in turn, see the new rankings in society’s unseen index. Instead, Yoruba parties are, instead, engineered for politics and not the kind you’d expect—certainly not the stuff on TV.

The Big Mummies, Nigeria’s real career politicians, are subtler and more strategic than their male, stomach-infrastructure-pioneering counterparts. The Mummies fight their battles in the finer details: in the artificial scarcity of invitation cards; in sequined subtexts or pearled platitudes; in the stratification of and, thus, discrimination by aṣọ-ẹbi; in seating arrangements (by the loudspeakers being the dungeon); in what denominations of naira they spray who—anything below a two hundred-naira bill being a red flag.

In Nigeria, prosperity is divine and poverty is a sin. Wealth, a symbol of prosperity, remains not the accumulation of material things but the amassing of respect, goodwill, recognition—the intangibles—even if unwarranted. To be wealthy, then, is to be preoccupied with the immaterial. Think of Mill’s “higher pleasures”: The art of spraying dollars (which is to do so like you despise the international monetary system, but gracefully); the philosophy behind the solipsism of having your name chanted by King Sunny Ade; the music of champagne bottles popping; the poetry of sycophants making small talk.

At Yoruba parties, your net-worth is ultimately your net-receipt of party gift souvenirs: soaps; china; coolers; stationery; phones; fabric; each one branded with the name of the celebrant (and, below, a customary “Courtesy of…”). Everyone contributes something; these parties being one of the earliest manifestations of the sharing economy.

Lowest of keys, souvenirs announce the winding down of the event. They emerge slowly in the clutches of—of course—Big Mummies, who wade through seas of wishing eyes, now having exchanged Yao Ming heels for flats or slippers. The music will have segued from live band to DJ, with songs less Juju and more Afrobeats-y as a way to zhuzh up the dance floor’s youth participation levels, and instagrammify the rocks with #AsoebiBellas, #YorubaDemons and #PepperDem gangs.

The distribution of party souvenirs and gifts for guests follows the rules of Nigerian economics: limited resources, unlimited disregard for actual economics. It occurs within a proximity to chaos that fuels excitement. Shadow economies fester in corner discussions and hot whisper sessions with Big Mummies premised on please Ma, sorry Ma and excuse me Ma. But you want to act like a packet of toothpicks is nothing until the person beside you receives one and you don’t.

For all our drama and party-politicking, Yoruba people are terrible pretenders. “Shine your eyes,” “Don’t sleep on top bicycle”, are not just other ways of saying stay woke, or random musings confined to the side of intercity buses, but the Nigerian philosophy on life. At a Yoruba party, recall that you are Ash in a forest of Pokémon—the plastic bowls, umbrellas, napkins are, indeed, yours to claim.

Necessity, Thomas Malthus wrote, is the mother of invention. So you want to approach that Big Mummy who just skipped you. And if she proves difficult, if she tells you there’s simply not enough to go around, you want to invent a new self. “Excuse me, but do you know who I am?” Scarcity has a way of bringing out the best and the worst in people. At a Yoruba party, both the best and the worst may very well be the same.