From slavery to colonialism and school rules, navigating the history of myths about black hair

“Your hair feels like pubic hair.” That was one of the first insults that someone hurled at my hair. She was a junior at my school. She would touch my hair and repeat this sentence to all present. I had to threaten her with violence to get her to stop touching my hair and comparing it to her pubes.

“Your hair feels like pubic hair.” That was one of the first insults that someone hurled at my hair. She was a junior at my school. She would touch my hair and repeat this sentence to all present. I had to threaten her with violence to get her to stop touching my hair and comparing it to her pubes.

This is one of the first dilemmas that black people face: do I let people touch my hair and under what circumstances? The question, “can I touch it?” becomes one of the most awkward social moments and can break relationships before they even start.

This fascination with the texture of black hair (please don’t call it “ethnic”), is not new. In slave societies, white women would often hack off the hair of their enslaved female servants because it supposedly “confused white men” .

Today, black women with nappy hair—that is, natural and chemical-free—are desirable despite the popular discourse to the contrary. Think for example of how Lupita Nyong’o has become a household name even though she is nappy and has dark skin.

It’s not just fashion or trends: throughout history, black women’s hair has fascinated artists and photographers and has been closely linked to radical political movements such as the Black Panthers and South Africa’s own Black Consciousness Movement. It then seemed like a paradox for the young women at South Africa’s Pretoria Girls High School when they were told they should “discipline” their hair by relaxing it.

Desire and fear

But it’s actually not a contradiction, since desire and fear often feed on each other. In the documentary produced and narrated by Chris Rock called “Good Hair”, the comedian Paul Mooney states it plainly: “If your hair is relaxed, white people are relaxed. If your hair is nappy, they are not happy.”

A trailer for comedian Chris Rock’s documentary “Good Hair”

This is not just clever rhyming. Mooney is pointing to the fact that nappy hair is inevitably associated with something that is out of reach for “white people”—happiness. When you sport your natural hair, you are free; your hair is wild; you have a new “hairstyle” everyday; you are radiant; you are regal. These are out of reach for most people and it makes them unhappy.

It is also about conformity. By choosing not to tease and tame your hair, you are also choosing to let your hair express its personality rather than look like everyone else’s hair. That’s why it makes people unhappy.

Notice that I have generalized the issue to people in general rather than writing about white people, because misconceptions about what black hair is are also propagated by black people. In fact, I would argue that most white people don’t know anything about black hair, and get most of their misconceptions about what it is from black people.

A history of black hair myths

There are two main misconceptions that are urgent for understanding what the governing body and headmistress of Pretoria Girls High may have been thinking—or not thinking.

The first misconception is that natural hair is “dirty”. The second is that natural hair does/doesn’t grow (hence the obsession with hair length, hair extensions and dreadlocks).

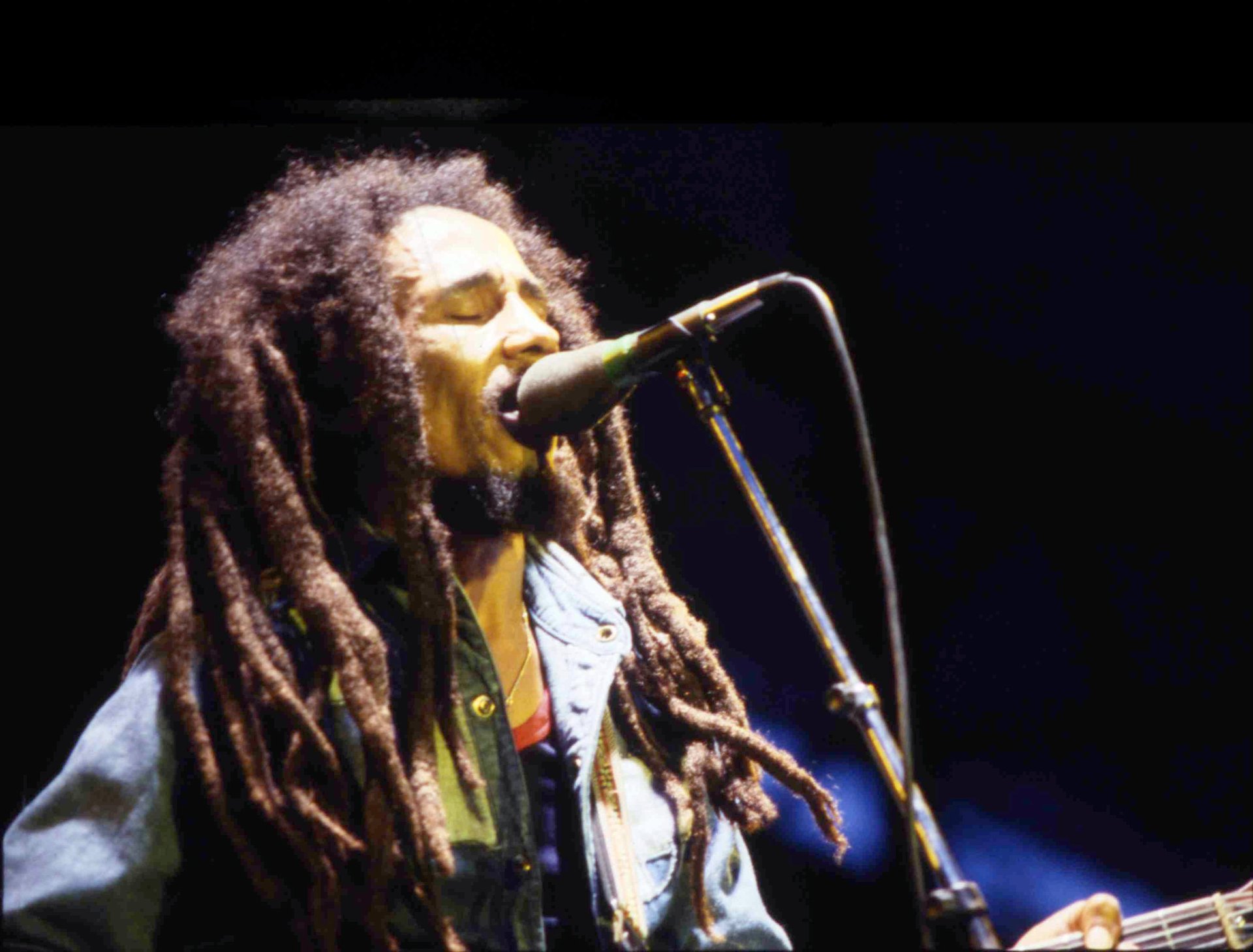

Many black women and men who wear weaves and relax their hair will explain their choice by either saying that their natural hair is “unmanageable” or that natural hair is “dirty”. This is one of the most enduring stereotypes about black hair. People will even cite the “anecdotal” evidence that Bob Marley’s dreads had 47 different types of lice when he died. These are urban legends of the worst kind because they perpetuate the stereotype that only black hair attracts lice, and other vermin, which is simply scientifically untrue.

These images are misleading for the simple reason that they suggest these Sudanese soldiers did not “dress” their hair or wash it, since in the images it often looks unkempt. Nothing could be further from the truth. Across the African continent, techniques for dressing hair were as varied as the hairstyles that they produced.Historically, the myth comes from images of the pejoratively named “fuzzy-wuzzy” that British soldiers who were fighting Sudanese insurgents in the Mahdist War sent home. This war, from 1881-1899, popularized the image of the wild Afros that people now imagine when they think of black hair.

The “Afro” therefore is not some kind of standard African hairstyle. It is just one of several hundred ways of growing and maintaining curly hair. So, when a black person decides to “dread” or lock their hair, they neither need nor keep “dirt” in it to make it lock. Our hair (as does all hair) locks naturally when it is left uncombed or unbrushed.

The association of locks with dirt partly comes from the Caribbean where Rastafarianism emerged as a subculture. However, even in this instance, the misconception is that dreadlocks equal Rastafarianism. The Rastas got their locks from Africa. To be exact, matted African hair was transported to the Caribbean by images of Ethiopian soldiers who were fighting the Italian invasion which began in 1935. They vowed – using the example of Samson in the bible – that they would not cut their hair until their country and emperor Ras Tafari Makonnnen (also called Haile Selassie) were liberated and the emperor returned from exile.

Before the war the Ethiopian elite sported very neat Afros. The only conclusion we can reach is that it is only under conditions of war and colonialism that black people present their hair as “unkept”. When at peace, the hairdressers and barbers did their jobs and kept black hair looking fabulous.

Policing black hair

The myths about how long black hair can or should be are as legion as the myths that natural hair is “dirty”. The misconception partly comes out of the concept of measurement. Natural African hair is curly and so to measure it, one would have to stretch out the coils. This is why limiting the growth of the hair by the width of cornrows or length of strands doesn’t make sense at all.

How would you know – without uncoiling it – how long a black person’s hair is? One black person’s coiffure will look very short because of “shrinkage” and another black person’s locks will look very long because of a loose coil.

The notion that long black hair is or should be cut or trimmed to an “acceptable” length is just ignorance masquerading as “neatness”. No two black people’s hair “grows out” the same.

Pretoria Girls High is not the first institution to try and police black people’s hair. In an article titled “When Black Hair Is Against the Rules”, the New York Times responded to hair regulations that had been published by the US Army on March 31 2014. These prohibited twists, “matted” hair and multiple braids – all of which were read as references to natural African hair and hairstyles.

Whose “common sense”?

Conservative institutions – schools, militaries, corporations and so on – have the right to prescribe a dress code. However, these should not be based on partial knowledge where these institutions simply don’t do any research into what some of their prohibitions actually mean and instead rely on “common sense”.

Unfortunately, when it comes to black hair, “common sense” is the least reliable tool for decision-making, since even black people are constantly changing their minds about what they want to do with their hair. As an expression of our culture, black hair is as malleable and plastic as our ideas about it.

To attempt to fix such expressions in rules and regulations is to deny black people what the Senegalese historian Cheikh Anta Diop called our “Promethean consciousness”. As black people, our hair is an expression of the infinite possibilities that emanate from this creative and daring consciousness.

Hlonipha Mokoena, associate professor at the Wits Institute for Social & Economic Research, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.