How a pan-African network of cyber activists has been strengthening democracy online

Dakar, Senegal

Dakar, Senegal

During a recent visit to The Gambia’s capital Banjul, digital activist Cheikh Fall spoke about the power of the internet to improve governance in Africa.

Fall, 35, is a co-founder of the pan-African network of online activists and bloggers for democracy (AFRICTIVISTS), a community of 200 cyber-activists from 35 different countries on the continent. The Africtivists were on tour to train 500 journalists in cyber-security, traveling from Guinea, Mauritania, Senegal, to Niger, and Burkina Faso.

In countries where occasions to gather in public spaces and criticize governments are slim or dangerous, the internet has become an arena for political battle. Governments, increasingly aware of this, have cut off the internet and blocked social media outlets, depriving activists of the tools to connect, collaborate and inspire action. The Africtivists created a network that would help organize across the internet, disperse messages, and amp pressure on governments to strengthen democratic rights and improve transparency.

“Africa will be left behind in the digital revolution unless it takes advantage to transform lives,” Fall said.

Inspired by digital activists of the Arab spring, the Africtivists’ online battle started a few years ago. Fall opened the way with his platform Sunu2012 (“Our 2012” in Wolof language) inviting citizens to monitor the Senegalese presidential campaign and notify him in case of irregularities in the electoral process. The same year, similar initiatives blossomed in Benin (#Vote229 in reference to the country code), Burkina Faso (#Lwili for Lwili Peende, a traditional Burkinabé cloth featuring a bird, much like Twitter’s icon) and Ghana (#GhanaVote), where activists were passing on any information regarding attempts at breaking the rule of law, the justice system, democracy, public liberties or good governance.

After years of online exchanges, the teams finally met up in Dakar in November 2015 and launched Africtivists. At that summit, they defined what would be their line of action: monitor closely that the rights of the citizens were being respected and when they weren’t, call out governments or help depose the African leaders who publicly flout the law.

“Our main focus is information. We want to equip citizens with tools to tackle dictatorships and censorship,” explains Fall, who does not define himself as a journalist but prefers the labels “concerned citizen” or “influencer.”

In just a few years, the Africtivists have learned to react quickly, in a structured manner. “When there’s a problem in Chad, DRC, Cameroon, everyone is up on deck,” says Chantal Naré, a feminist blogger from Burkina Faso. “We start passing down the info on our networks and immediately release a statement,” adding, “African dictators are afraid to see us all together sharing the same vision for a new Africa.”

The Africtivists’ most impressive feat remains when former dictator Yahya Jammeh relinquished power in January 2017 after 22 years as president of Gambia. The cyber-activists claim partial authorship of this unexpected outcome. “We had been working on this case for two years,” remembers Fall. “It had taken a lot of our time and energy. We were constantly fact-checking him. A lot of Gambian journalists were working in exile from Dakar.”

Among them is Aisha Dabo, who initially came for a one-month training at the Senegalese capital and ended up staying after she learned the newspaper she was working for in The Gambia had been shut down without notice.

Dabo threw herself into the campaign launched to raise awareness of Jammeh’s dealings using the hashtag #jammehfact. When Jammeh refused to leave his seat to his newly elected successor Adama Barrow, the Africtivists hired a European firm to send mass messages to military officers likely to support a coup: “Choose Gambia, choose the people!” the messages read. They also sent letters to wives of army officers, urging them to talk to their husbands.

Among other tools, the Africtivists set up a pirate radio station which works only in moments of crisis. “It had been in our plans for a while now, but the events in The Gambia accelerated its birth,” Fall notes. Launched in The Gambia in 2016, the radio’s content is produced by staff members of temporarily shut down radio stations. It broadcasts on the web and on the darknet.

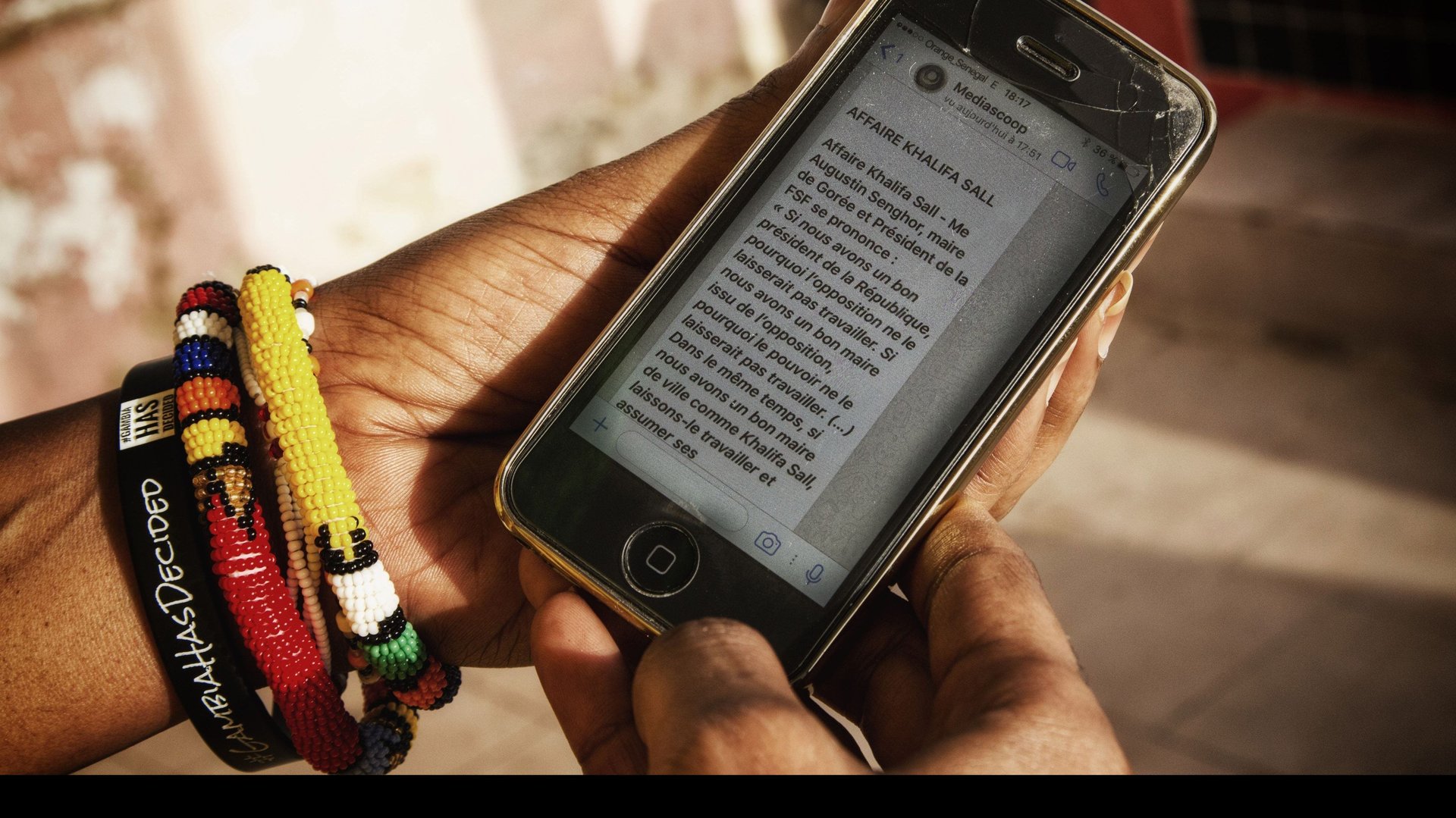

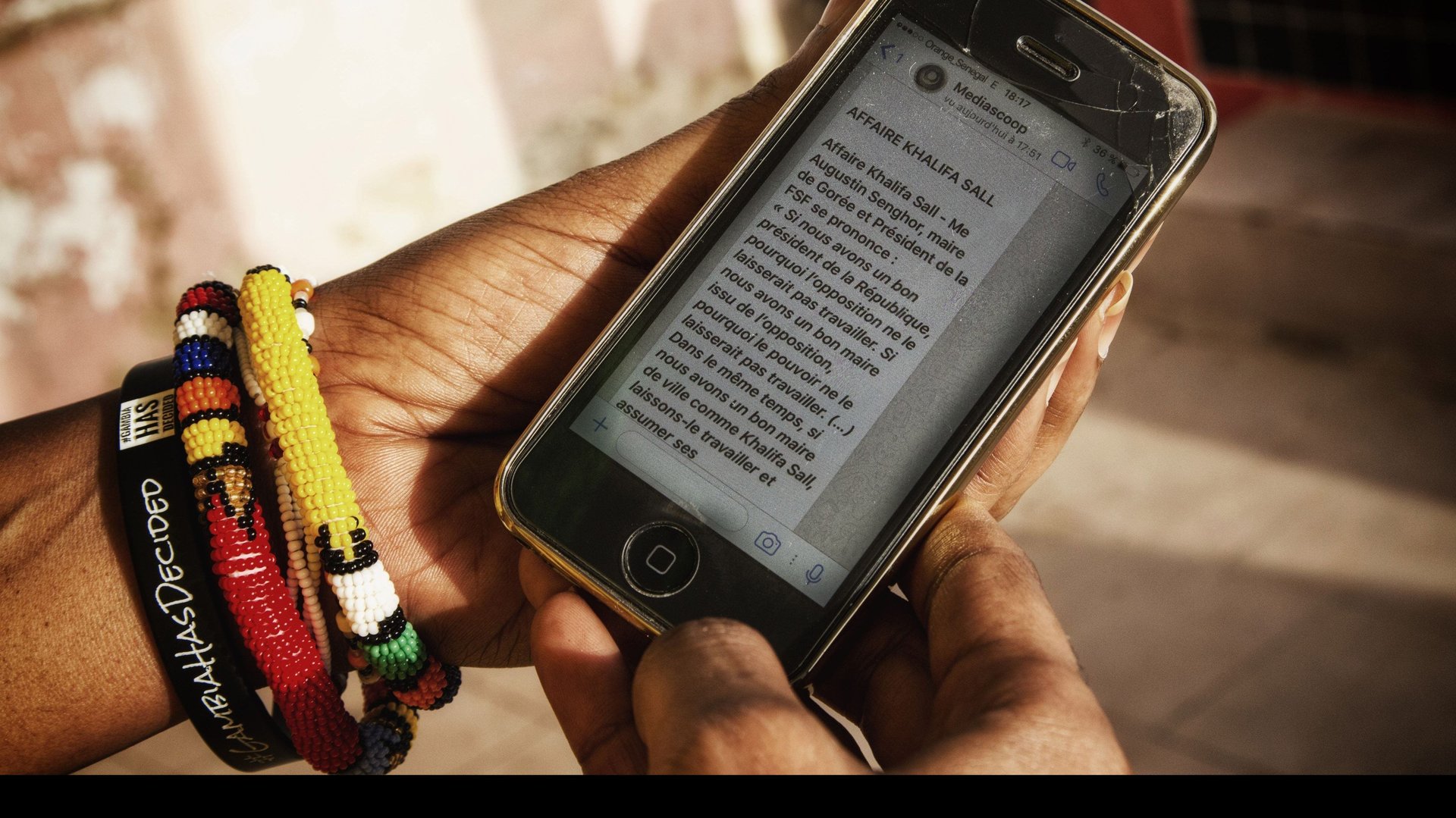

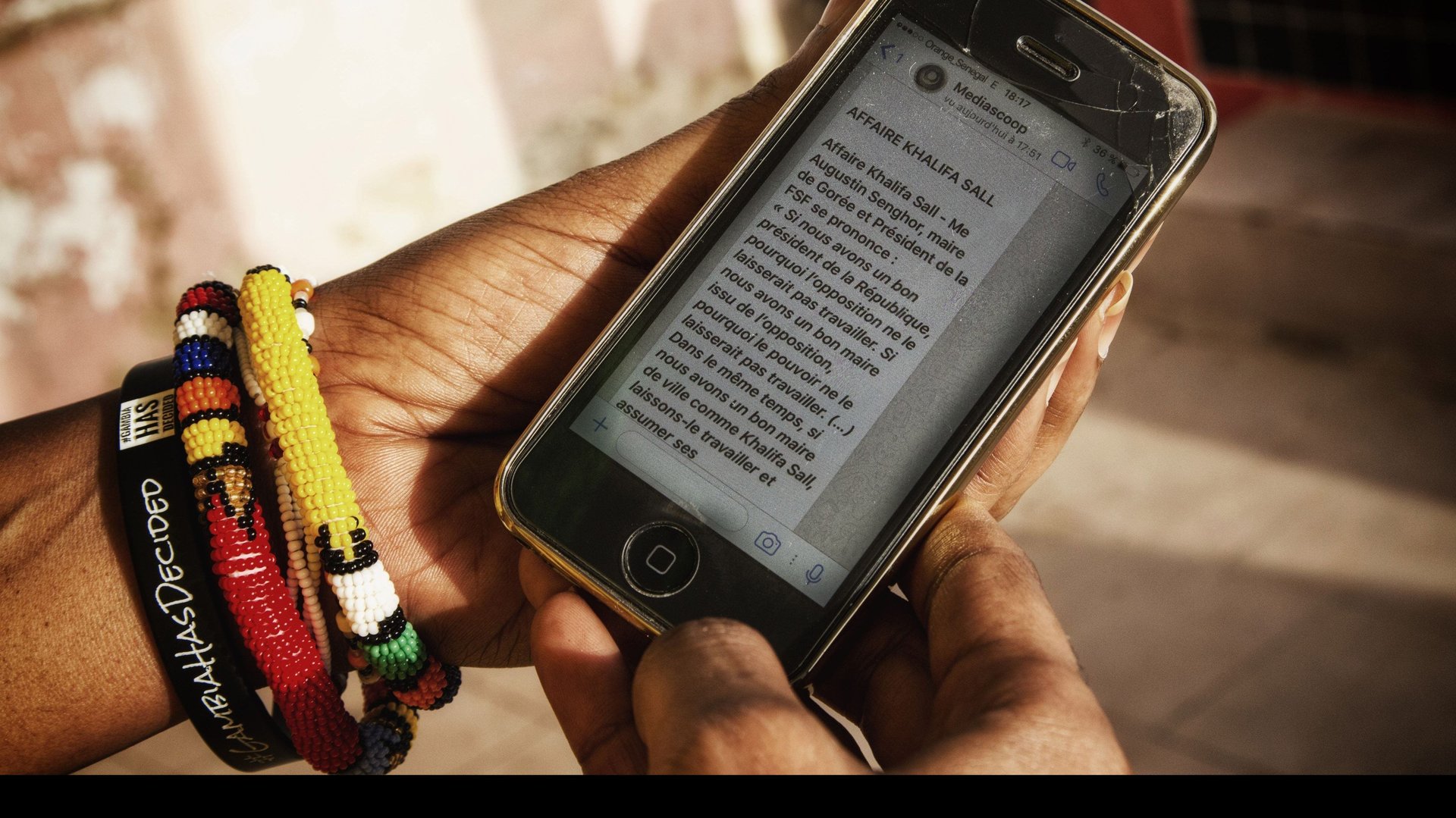

The Africtivists also launched MediaScoop, a service which irregularly sends flash news through Whatsapp. The team hopes to reach 1 million users in Senegal in 2019 when the country holds its presidential election. “If this format works, we’ll test it in other countries as well,” says Fall.

What the Africtivists refer to as a “cause” takes a lot of their free time. Many of them have day jobs: Fall defines himself as a consultant for international organizations, while Naré is employed by a non-governmental organization that she declines to name.

And even though Fall argues that “we are not a secret society,” the team is also discreet on its sources of funding. Partly self-financed, the project is also funded by the Open Society Initiative for West Africa, the George Soros foundation, and European embassies. They also receive technical support from Clemson University in South Carolina when it comes to matters of cybersecurity. The group has also worked with internet advocacy groups Article 19 and Internet Without Borders.

Malick Fall, the Senegal program associate at OSIWA said their support to the group “was meant to help them organize, share experiences, build their capacity and advocate for a democratic consolidation of Africa.” Besides Senegal, Fall says the activists have carried out online campaigns in Burkina Faso (#Iwili), Guinea (#GuineeVote), Niger (Just1pourcent), and The Gambia (#FreeSanna), and Cameroon (#BringBackOurInternet).

Henri Thulliez, from the Belgian foundation Equal Opportunities in Africa, says the team’s “dematerialized activism” is essential in creating a more powerful network. “This is a new kind of Pan-Africanism,” he said.