Black Panther’s Wakanda has historical roots in nuclear-age Congo

Marvel’s Black Panther sold more tickets to its opening weekend than any movie in history, and the New York Times has called it “a defining moment for Black America.” The Black Panther himself is T’challa, the king of Wakanda, a mythical African nation that also happens to be the world’s most advanced civilization.

Marvel’s Black Panther sold more tickets to its opening weekend than any movie in history, and the New York Times has called it “a defining moment for Black America.” The Black Panther himself is T’challa, the king of Wakanda, a mythical African nation that also happens to be the world’s most advanced civilization.

The buzz around the movie’s release has been filled with questions and discussion about the titular hero’s homeland. But, often lost in all the excitement is the fact that the fictional story of Wakanda has real historical roots in nuclear-age Congo.

The secret to Wakanda’s superiority is vibranium, an indestructible alien element that is found only in Wakanda but is in great demand by both scientists and evil-doers. The source of vibranium is a meteor that landed in the country long ago, and T’challa’s father kept it secret from the world as he developed his nation.

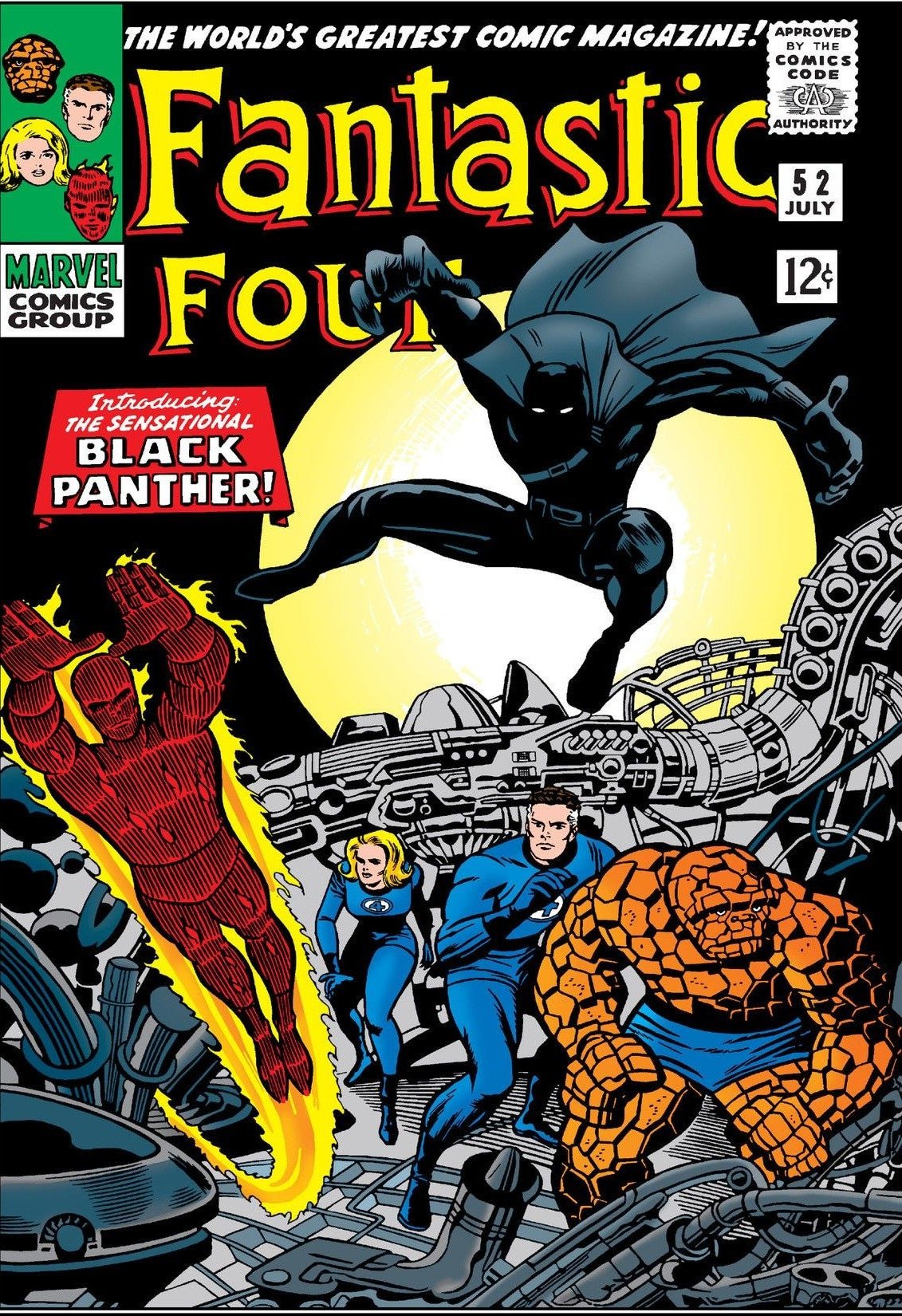

The Black Panther and Wakanda first appeared in Fantastic Four #52 (July 1, 1966) and his story was elaborated in the next issue (#53, August 1966). Marvel Comics’ dynamic duo Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created the character. His debut was more than three months before Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California in October of that year.

Wakanda’s location has shifted over time and writers have attributed various African inspirations for the story. But the Black Panther’s back story makes clear that the Congo was Lee and Kirby’s imaginative jumping off point for Wakanda.

When Marvel published its Marvel Atlas #2 in 1988, Wakanda was near Lake Turkana (northwestern Kenya, near the Ethiopian border), and was near the fictional nations of Canaan, Niganda, Rudyara, Ujanka, Ghudaza, Mohanda, Zwartheid, and Azania.

Some have looked to the Monomutapa civilization of Great Zimbabwe as the inspiration for the Black Panther story. The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, who has penned the storylines for the Black Panther comic since 2016, has also pointed to Ethiopia, a country that defeated Italian forces in 1896 and remained independent during the colonization of Africa, as the inspiration. The movie’s director Ryan Coogler has said that he was influenced in part by his trip to Lesotho. The small kingdom, surrounded on all sides by South Africa, avoided the worst of colonialism.

But to locate Lee and Kirby’s original idea in 1966, the comics provide better clues.

T’challa explains his own history and that of his country in Fantastic Four (#53). Mr. Fantastic, Reed Richards, notes that “Though the Wakanda Tribe lives in the tradition of their forefathers, they possess modern super-scientific wonders we can only marvel at!” T’challa then tells Richards and his friends that western greed and a quest for African resources had disturbed peaceful Wakanda.

It was not just a “greedy ivory hunter,” but someone much more dangerous. The evil Ulysses Klaw sought out vibranium as “the one element I need—the one element which will power” his all-destructive weapon, a sound transformer that could convert the energy of sound into living forms. When T’challa’s father, T’chaka tried to prevent Klaw from controlling the vibranium supply, Klaw had him killed. T’challa witnessed this as a boy and vowed to avenge his father’s death.

Lee and Kirby had both served in World War II. Working in 1966 they were steeped in the science and technology of their day: the nuclear era and the space age.

In 1961, they had created the Fantastic Four, a foursome of American astronauts whose exposure to cosmic rays gave them super powers. The next year they rolled out the Incredible Hulk, the green monster alter ego of scientist Bruce Banner who emerged after Banner was exposed to gamma rays during the detonation of a bomb. In 1962, Lee introduced the Spider-man, an unlikely hero created after wallflower teenager Peter Parker was bitten by a radioactive spider. The following year, Kirby and Lee teamed up launch the X-Men, a group of human mutants who were born with super powers.

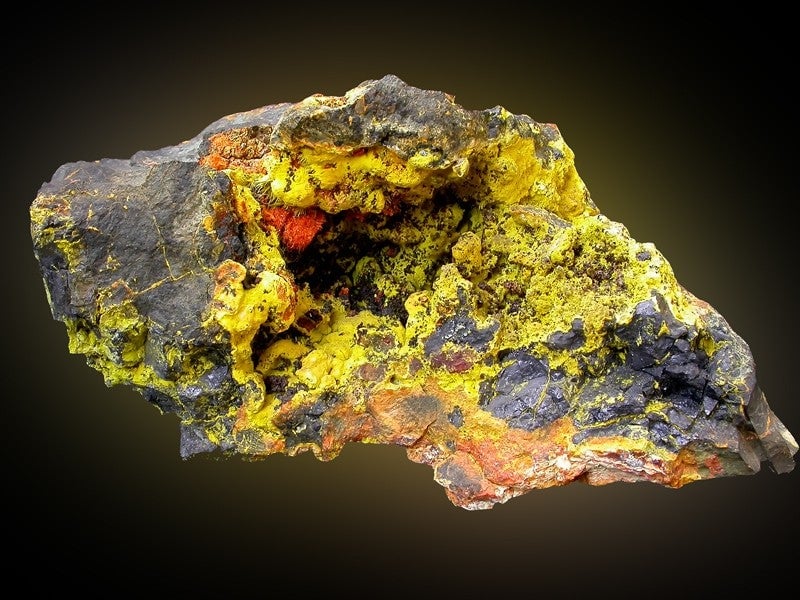

After exploring the possibilities of radiation and mutation, it is no wonder that they turned their attention to the source of such powers. Indeed, in the half-decade before the Black Panther appeared to protect vibranium, the world had watched a struggle for the control of the source of another element that could power fearsome weapons: uranium, and it was found in the Congo.

The Shinkolobwe mine contained the richest deposit of uranium anywhere on earth, and it just happened to be in Congo’s Katanga province. Albert Einstein had written to president Franklin D Roosevelt in 1939 about Enrico Fermi’s atomic work and the potential for a weapon. They would need high quality uranium, and Einstein noted, “The most important source of uranium is in the Belgian Congo.”

In 1945 uranium from Shinkolobwe was used in the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, and protecting the mine during and after the Second World War had involved deep espionage.

When the Belgian Congo became independent on June 30, 1960, what would happen to its uranium? Who would control it? Less than two weeks later, Katanga seceded from the Congo under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe, with the support of Belgian industrial and military interests. Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s Prime Minister, sought to regain control, and called on the United Nations for help. When the UN was reluctant to subdue the Katanganese rebels, Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union.

In the resulting Congo Crisis, Lumumba was overthrown and assassinated in 1961, and the UN Secretary General was killed in a mysterious plane crash later that year. As the crisis unfolded, American support helped defeat forces that remained loyal to Lumumba.

In the US, Malcolm X injected Lumumba and the Congo strongly into debates about African American rights. Malcolm X called Lumumba “the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent;” criticized the Johnson administration’s support for Tshombe; and called on black veterans to go fight in the Congo. If Congo was controlled by a “real dyed-in-the-wool African nationalist,” Malcolm X argued in New York in December 1964, it would bring an end to white rule in southern Africa (Angola, Southern Rhodesia, Southwest Africa, and South Africa).

He also linked the US civil rights movement to the Congo: “the same schemes are at work in the Congo that are at work in Mississippi.” African representatives at the UN picked up this comparison, and the New York Times covered it.

Malcolm X lectured on Lumumba and the Congo until he was assassinated in 1965. Later that year, the Congo Crisis came to an abrupt end. Army chief of staff Joseph Mobutu’s coup d’état put him in charge of a unified Congo. Mobutu, a ready ally of the United States, assured that the world’s most important deposits of uranium would not fall into Soviet hands.

So the origin story of Black Panther introduced in 1966 looks like what would have happened if Batman/Bruce Wayne’s parents had been Patrice Lumumba and Malcolm X. In the face of their murder, the loyal son dons a mask and uses the wealth at his disposal to avenge his parent’s death.

For Black Panther, this also meant keeping the world safe from the misappropriation of vibranium. And Black Panther took on white supremacy. As his story line developed, Black Panther fought apartheid in South Africa and the Klan in the southern United States.

We can now locate him in the pantheon of Marvel heroes and as the star of his own feature film. When we go looking for Wakanda, however, we can find it in a Cold War crisis and an African mine.

This story first appeared on Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective. Follow @OriginsOSU on Twitter.