Cheese, salad, and bland potatoes: The underwhelming culinary experiences of a Nigerian palate abroad

My Chilean friend Carolina Melendez and I once traded airplane food stories. Hers was egusi soup on the last leg of her trip from Kuala Lumpur to Lagos. She used the word ‘pungent’ in describing her first impression of the soup and I tried to do a quick estimation of the number of times I have heard the words ‘egusi’ and ‘pungent’ in the same mouthful of air. She said egusi soup looked and smelled like some kind of egg dish gone bad, and it was and it was a very bad smell.

My Chilean friend Carolina Melendez and I once traded airplane food stories. Hers was egusi soup on the last leg of her trip from Kuala Lumpur to Lagos. She used the word ‘pungent’ in describing her first impression of the soup and I tried to do a quick estimation of the number of times I have heard the words ‘egusi’ and ‘pungent’ in the same mouthful of air. She said egusi soup looked and smelled like some kind of egg dish gone bad, and it was and it was a very bad smell.

My story was of heading to London for the first time at 16. My airplane meal was supposedly three courses: a salad that, to my Nigerian sensibilities, was really only incidental to the main meal, which was familiar but insufficient to feed a toddler. There was a dessert course of cheese with three diminutive crackers; nothing like what I expected a sweet course to be. It should, at the very least, have been sweet. I ate the main course wishing it was larger, nibbled on the biscuits and the rubbery triangles of cheddar, riffled through the salad for anything resembling meat, and wondered—still ravenous—why, over the Atlantic, the British had to live up to their reputation of being as tight as Japanese handbrakes. Why not persevere till we landed in Heathrow?

No sooner were my bags unpacked at my aunt’s house than I had to get the issue of the meal on the plane off my chest. She laughed and explained that the British don’t eat like us. Nigerians would be happy to eat one course at the most sophisticated of dinners, and that course would only need to be served in generous portions or include a variety of dishes. The quality, variety, and size of the meat portions would most accurately indicate the importance of the occasion, not the number of courses. If one served five courses of salad without meat or fish to the average Nigerian at a dinner party, he would not be impressed by the variety of vegetables. He would be urgently looking about for the meat and the rice, the fried rice, the jollof rice.

In order to be satisfied with my airplane meal, my aunt said sympathetically, I was required to eat all of the bitter cos in the salad, all of the main meal and all of the cheese and biscuits, as well as the five or so perspiring grapes.

It was an important precursor to the many disappointments with food I encountered in cosmopolitan London, Wolverhampton and Cardiff.

The lasagne was too cheesy and milky, making me exceedingly gassy. There was a strong suspicion that I was lactose intolerant. My father had warned me that many southern Nigerians are.

The delicious-looking potato bake smelled divine—the aroma of the tomatoes spread on the potatoes prickled in the nostrils, and set off some undignified watering of the mouth—but the whole thing tasted overwhelmingly of tart, barely cooked tomatoes that, in Nigerian lingo, ‘slapped you’. It was completely pepperless to boot, and the potatoes had not browned in the whole enterprise. They were just-cooked potatoes, with no edge, no crunch, no golden colouring, confounding my Nigerian palate.

The pesto was murky and alien, with a brawny taste of fresh grass. The greenness of the smell was familiar, like a milder form of the smell of bitter leaf, or afang leaf maybe. It looked like cooked afang but there was no comforting palm-oil liquor on its face. It had pine nuts, which I had never heard of, and cheese. Cheese! Anything that uncomfortable-looking surely had to be eaten either with discretion, for medicinal reasons or be a laboriously acquired taste.

The doner kebab was nothing like suya, and if you wrung it you got a bucket full of grease. It didn’t come with the smell and decoration of newsprint, or the groundnut, pepper, and ginger to sprinkle on top. There were no crunchy red onion slices, no juicy fresh tomato chunks. The roasted chicken flesh came off still-bloody bones like toilet paper. The chicken was as bland as toilet paper too. The steak and kidney pie was as phlegmatic as a NIPOST clerk. It could never in a million years hold a match to the ubiquitous shortcrust pastry meat pie that you bought from Munchies in Lagos.

Even the Jamaican patties stood outside my visual comfort zone with their bright turmeric colour. Everything except Yorkshire pudding was overrated, inappropriately bland and in need of a dash of Tabasco sauce, which I carried about in my bag. I discreetly laced a few chocolate mousses with Tabasco sauce out of desperation for crawling, walking, burning heat on my tongue. My disappointment was deepened by the fact that I had spent so many years staring at Jeni Wright’s All Colour Cookery Book. Lasagne and steak and kidney pie had looked unarguably delicious on the pages of that book.

After spending three years studying an undergraduate degree in Wolverhampton and eighteen months on a master’s degree in Wales, I did learn to love Gruyère cheese quiches. I could even keep down some blue Stilton if there was something to counteract the saltiness, like an apple. I bought mutton neck and small, brittle-boned chickens from local halal meat shops. I discovered the health food fringes embellished with creative treats: delicious, seeded handmade bread, goat’s milk butter and home-made jams. I made stew from sweet red peppers, canned tomatoes, onions and Scotch bonnets. I never made friends with baked beans, never joyfully ate a teaspoon of the stuff. I binged on freshly baked Yorkshire pudding. I resolved that if I had been fed Yorkshire puddings and water on my flight out to the United Kingdom, I would have been blissfully happy, and thought better of the British.

No one ever said to me, ‘Right Yemisi, tell me all about Nigerian food.’ Angelos, boyfriend to a Greek postgraduate housemate in Wales, came up to me one day while I was cooking and asked if I was cooking tiger or lion. He didn’t wait for an answer. He grinned and told a long anecdote about an old housemate who cooked Nigerian food all the time and how the food and the house ‘smelled like shit’. I spent a week with a family in Poole who cracked endless jokes about ‘African chickens’ being like vulture meat, and ‘swallow’ and ‘draw soup’ being like starch and glue. This family had lived as missionaries in Uganda and believed that they were experts on all things ‘African’.

There was the inscrutable conclusion that the food I ate at home in Nigeria was “African.” It was “jungle fare.” It was something you ran out to the bush for. It was cantankerous and makeshift. It jumped off the plate and fought you for the spoon. The anecdotes for the week I spent with the family in Poole were nightly affairs, told with sniggers over dinners that felt rationed and miserly. If one could have Yorkshire puddings and roast, why on earth would one want Nigerian food? So you didn’t need to ask Yemisi about Nigerian cuisine. She was living the life in Britain eating British food.

The egusi soup on the plane could indeed have done with a makeover. It didn’t need to overwhelm the cabin with the smell of dawadawa. It might have needed a bit of PR to tailor it to the context. But to be fair, when people talk about food being smelly, sometimes all they mean is that it is unfamiliar. After all, this same Carolina Melendez who said egusi soup was smelly was once caught trying to smuggle a durian fruit on a taxi in Malaysia. The taxi driver’s nose caught a whiff of what has been described as ‘a smell from hell’. She and her fiancé were asked to disembark the taxi with their precious durian. They could have fared worse; it is illegal to carry a durian fruit in a taxi in Malaysia. Perhaps the egusi needed a manual saying it was made from melon seeds, not eggs and that it had fermented locust beans in it. Perhaps the airline that went through all the propaganda effort of turning dull crackers, cheap cheese and four or five grapes into dessert should have called an expert to interpret egusi soup for high altitudes.

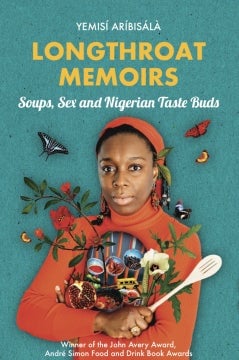

Excerpted from Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex And Nigerian Taste Buds (Cassava Republic). Copyright 2016.