It’s time to digitize the shared savings method African grandmothers have used for years

South Africans are bad at saving, or at least it seems that way from the formal financial sector. Yet, a centuries-old model of collective savings reveals a financial savvy that has long been ignored by the banking sector.

South Africans are bad at saving, or at least it seems that way from the formal financial sector. Yet, a centuries-old model of collective savings reveals a financial savvy that has long been ignored by the banking sector.

Stokvels have been around since the 19th century when English settlers held rotating cattle auctions known as stock fairs. Locals, mainly black South Africans, would pool their resources to acquire cattle and adjust to this imposed colonial financial system. It’s a system that remains today, and is now used to pay for everything from Christmas lunch to funerals. Now, the digitization of stokvels aims to empower a powerful but ignored sector of South African consumers.

Growing up in Soweto, Tshepo Moloi had firsthand experience of the advantage of this collective savings tradition when his own family stokvel contributed to his university tuition. As an adult when he tried to start his own stokvel, he encountered the kind of headaches that made stokvels feel like they were still stuck in the previous century.

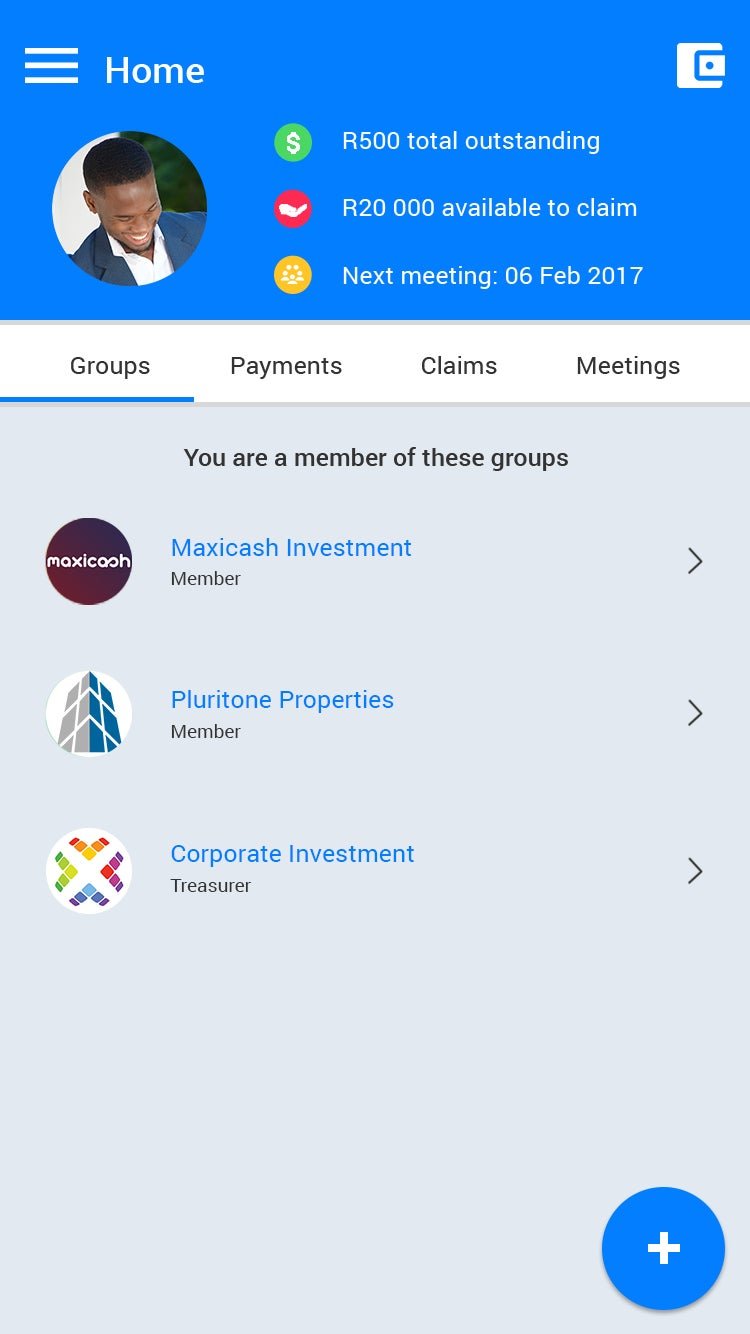

Just checking the balance of his stokvel, monitoring money coming in and out and keeping track of meetings became the kind of administrative nightmare that hindered growth. He also found that these were some of the common reasons people abandoned stokvels before they reached their potential. So in 2016, Moloi and his business partner Ruddy Mukwamu created the app Stockfella.

Along with an emphasis on accessible tech, the philosophical aim of Stockfella was to help stokvels understand their inherent value. By watching the money grow and accumulate interest, stokvel members had a clear understanding of the value of a lump sum savings.

The visual aspect of the app also aids in basic financial literacy for members who have a very basic understanding of banking and debits and credit, says Moloi. Further, Stockfella offers financial literacy workshops to users, in which they would meet with the group to teach them how to maximize their savings.

This aspect was particularly important to Moloi who watched stokvels never really achieve the potential they could. Stokvel members clearly know how to save and understand investment in a pedestrian manner, but they’ve been largely excluded from South Africa’s banking sector.

Stokvels are still regarded as an alternative form of saving, and yet they are how the majority of South Africans save. South Africa has over 800,000 known stokvels, representing an estimated 11.5 million people, according to the National Stokvel Association of South Africa.

Black households collectively in South Africa contribute more than 500,000 rand per month (over $40,000) to their respective stokvels, according to research (pdf) by Old Mutual bank. About 42% of urban South Africans who earned above $3,200 (above 40,000 rand) a month and 44% of those who earned $1,600 (more than 20,000 rand) belong to a stokvel, according to Old Mutual.

Considering 40% of South Africans struggled to make their credit repayments there seems to be a dissonance between the 50 billion rand ($4 billion) in stokvel contributions South Africans saved in 2017 and the level of indebtedness in the country. Most of the country’s major banks now offer stokvel savings accounts, but they limit what a stokvel can do (like invest on the stock market) and confine these savings to low-interest accounts.

Moloi says definitions of saving methods should be reconsidered to really understand and explain how the majority of South Africans save.

Initially, the primary aim of Stockfella was just to manage stokvels. The first 400 groups to join taught Moloi and his team a tough lesson in supply and demand, creating an app that gave people what they really needed, not what he thought they needed.

“We have a homogenous solution but the truth is every stokvel is unique so we have to try and cater to that,” Moloi told Quartz. Since stokvels save with such a diverse set of goals, they quickly learned that the app had to do more than track money. Stockfella has since evolved beyond an app into an independent financial entity that offers its members accounts and enables them to buy shares and unit trusts to turn their collective savings into a competitive investment.