How Cape Town delayed its water-shortage disaster—at least until 2019

Cape Town was on the brink of disaster, and then it wasn’t.

Cape Town was on the brink of disaster, and then it wasn’t.

For months, the clock on Cape Town’s water dashboard counted down ominously to Day Zero—the day the drought-stricken city would eventually run out of water. And then in February, it was pushed all the way to July. The latest count doesn’t even have a date, only that Day Zero may still happen in 2019.

Calculating Day Zero took into account maximum evaporation (based on temperature and wind) and existing patterns in agricultural and urban use—an equation that considered both natural and man-made conditions. Avoiding Day Zero has been a combination of both human effort and good rain. It’s also why Day Zero remains an ever-present threat, albeit one further out on the horizon.

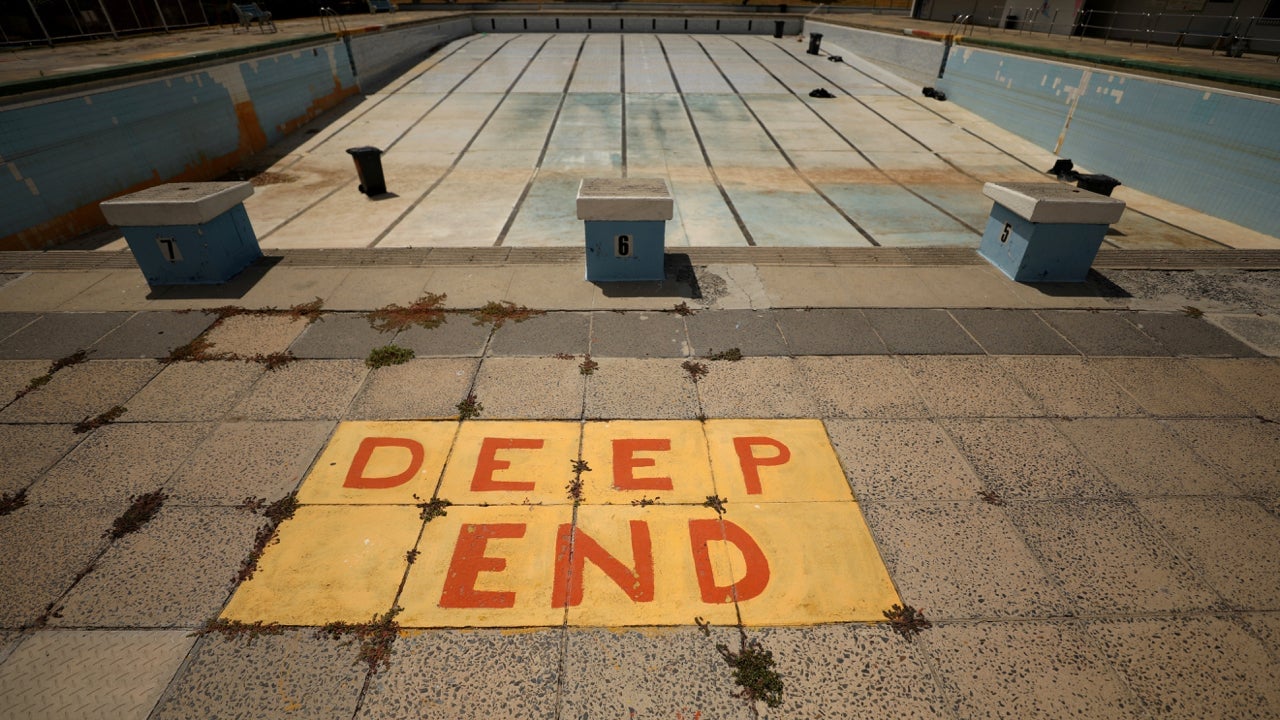

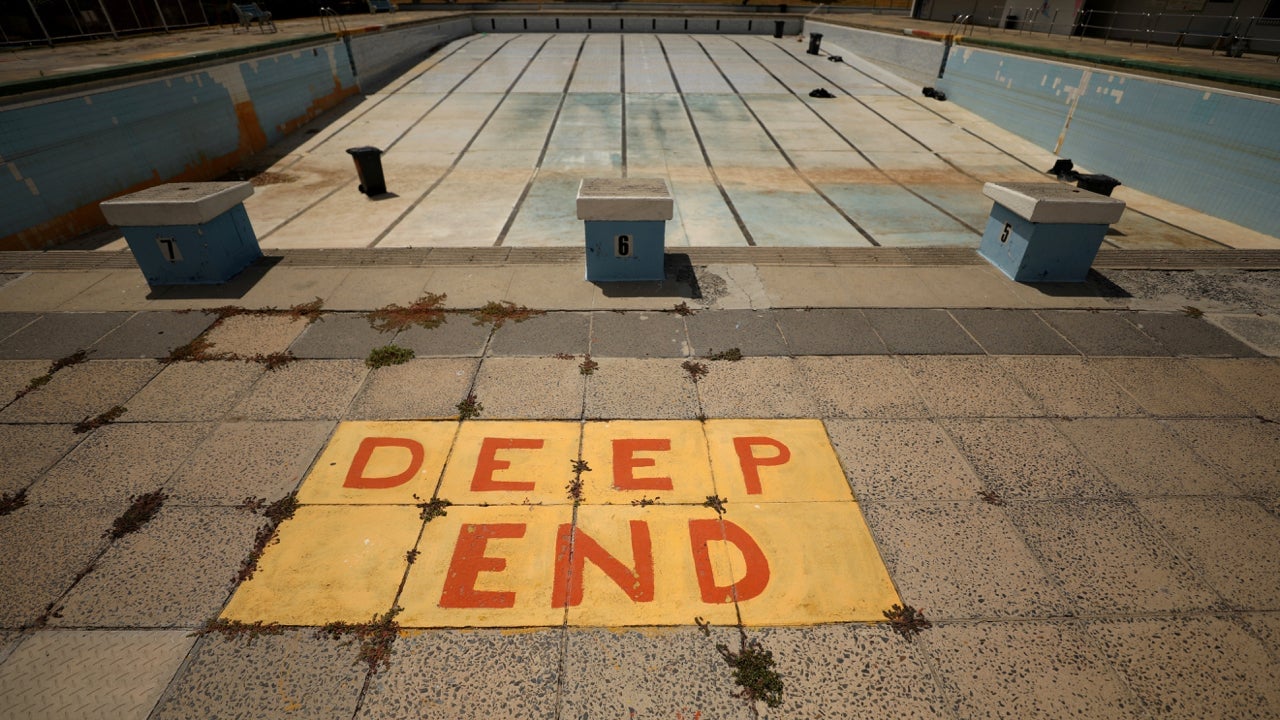

At the height of the crisis, Cape authorities leaned heavily on household users. Under certain restrictions, Capetonians were not allowed to use more than 50 liters of water per day. Practically, it meant that gardens went dry, showers were restricted to two minutes and swimming pools were almost a disgrace among neighbors.

Even at easier restrictions of 87 liters per day, the city publicly shamed water offenders, with the now former mayor visiting the homes of water wasters and her office publishing a list of the top 100 offenders. For the most part, residents played their part and cut water usage by more than half.

With Day Zero now pushed out, water usage has increased and city authorities are warning that if more severe restrictions aren’t adhered to, Day Zero could soon become a definite date again. One way to keep usage in check is a proposed tariff increase of 27% for water usage, with pricing also tiered according to average water usage. For drinking water, the price could double, from 26 rand per kiloliter to 40 rand (from just under $2.10 to $3.20). There is already pushback against the increase, with business and residents association planning to oppose the hike.

The single cause of Cape Town’s water crisis is still up for debate. Analysts argue that it was a combination of factors that included climate change, poor infrastructure planning and, politicking in a contested region.

One of the fundamental problems was that the city’s water storage had not kept up with population growth. Since the end of apartheid, Cape Town’s population grew from 2.4 million in 1995 to 4.3 million people in 2018. At the same time, the city only built one major dam, the Berg River Dam opened in 2009, increasing storage by 15%, according to local grassroots agency GroundUp. The lack of focus on infrastructure has been blamed on politicking and personality politics.

The city denies that storage is a problem. “The problem is not the storage; it’s that the water falling from the sky is not enough,” the water department’s Rashid Khan told radio station Cape Talk. “We have six dams. It’s enough. It’s about how to manage the water in the dams.”

At the height of the drought, surrounding farmers helped Cape Town’s city stave off Day Zero by dramatically reducing their own usage so that they could even donate water. The farmers had learned something city-dwellers hadn’t yet: how to live on the frontlines of climate change. For now, Cape Town’s winter rainy season has been heaven-sent, but scientists warn that this drier climate could be the new normal, a problem more difficult to solve than the water-use habits of the city’s inhabitants.