A major real time vaccination test is underway in the race to beat Ebola

In the next few days, the world will find out whether it’s possible to stop an outbreak as relentless as Ebola.

In the next few days, the world will find out whether it’s possible to stop an outbreak as relentless as Ebola.

On Monday (May 21), a vaccine for the deadly virus was tested in its first real-world outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In what is the ninth Ebola outbreak since 1976, the DRC has learned how to effectively manage outbreaks and reduce fatalities. This time could be different as the disease has spread to a large city.

Since the first diagnosis in April, 26 people have died out of 46 infections, according to the World Health Organization. Most of the cases occurred in the rural town of Bikoro, but the outbreak became more ominous when it spread to Mbandaka, a city of about 1.5 million.

A port city, Mbandaka lies on the Congo river, with regular downstream trips to the capital Kinshasa—a densely populated city of 10 million. Nine neighboring countries, including Cong-Brazzaville and the Central African Republic, have also been put on alert. It’s not a global health emergency yet, says WHO, but without a “vigorous response…the situation is likely to deteriorate significantly.”

More than 7,500 doses of the vaccine have been sent to the DRC, the vaccine alliance Gavi said in a statement. Vaccination will be carried out in the same way doctors eradicate smallpox, with the ring method. Researchers are racing to identify the contacts of those infected, and the contacts of those contacts to “form a buffer of immune individuals to prevent the spread of the disease.”

Health workers and other frontline responders will be among the first to be vaccinated, following the death of a nurse over the weekend. The vaccine is still in the investigational phase and has not been licensed. Still, in a major trial involving 5,387 people in Guinea toward the end of the West Africa outbreak, researchers found the vaccine to be “highly protective against the deadly virus,” according to results published in December. Immunized health workers from the Guinea trial will also be flown in to lend their expertise.

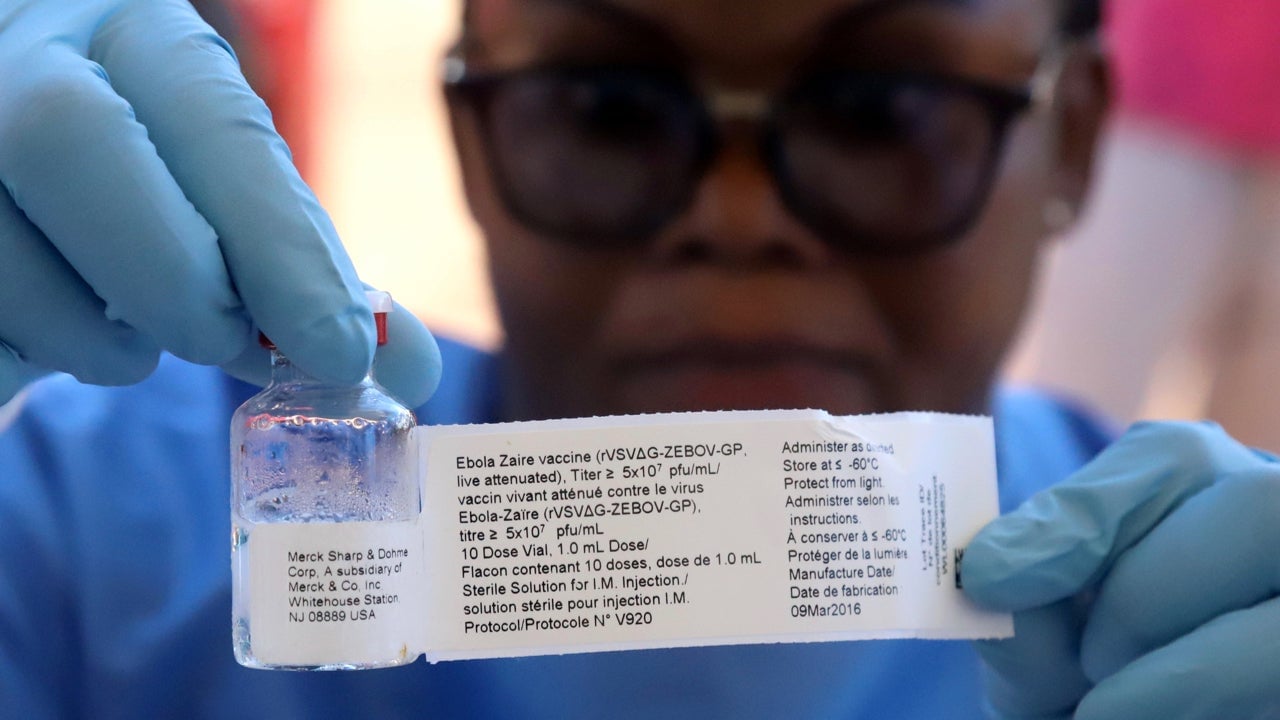

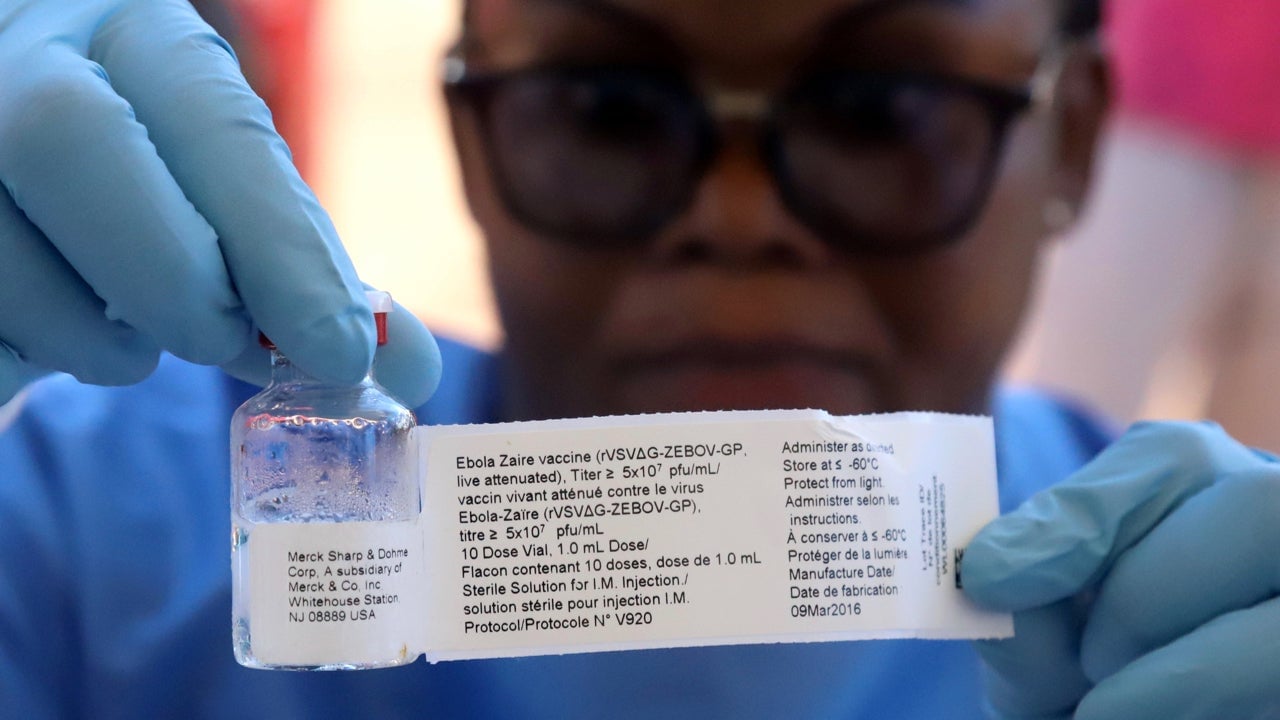

The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine was created by re-engineering the vesicular stomatitis virus, which mainly affects horses and cattle, to carry a particularly deadly strain of Ebola first identified in the then Zaire (now DRC), and is also the strain that caused the West Africa outbreak. Produced by pharmaceutical company Merck, the vaccine has been sent to the DRC “for compassionate use,” while it awaits final commercial approval.

The vaccination procedure is also a complex one: the vaccine must be kept at a temperature of between -60 and -80 degrees centigrade, which makes it difficult to transport. For now, WHO has deployed special refrigerated carriers as it tests best practices. The rapid response is not only a test for the future of combatting Ebola, it also signals the hard lessons the WHO learned during the West Africa outbreak.

A hemorrhagic fever, Ebola spreads quickly through contact with bodily fluids. In an urban setting, this infectiousness is a disaster. It’s part of what contributed to the rapid spread of the outbreak in West Africa, which killed more than 11,400 people between march 2014 and January 2016.