Heroin may be Mozambique’s second largest export—and it’s being disrupted by WhatsApp

Mozambique only has one reliable road running from the north to the south of the country, and yet that road has become the backbone of the lucrative heroin trade.

Mozambique only has one reliable road running from the north to the south of the country, and yet that road has become the backbone of the lucrative heroin trade.

Heroin is likely Mozambique’s largest export since the end of the war, according to a new report that details this underground industry. Officially, its two largest exports in 2016 were raw aluminum and coal, worth $378 million and $678 million respectively. Electricity exports also made $378 million in 2016. Exporting heroin brings in about $20 million per ton, with estimates ranging from 10 to 40 tons of the drug moving through Mozambique each year, according to a new report.

In the more than two decades since the end of Mozambique’s civil war the heroin trade has developed into a tightly regulated network operated by connected families and allegedly sanctioned by the political elite, according to “The Heroin Coast: A political economy along the eastern African seaboard,” a report published this week by the EU-funded Enact project, focusing on transnational crime.

Now, that illicit elitist grip is being loosened by improved cellphone signal in tandem with WhatsApp and other messaging apps. In a separate, more detailed outtake of the east Africa report, London School of Economics research fellow and former journalist, Joseph Hanlon has observed the “uberization of Mozambique’s heroin trade.”

Since the end of the civil war in 1992, Mozambique has become an important transit point in the global drug trade. Unlike Tanzania and Kenya, Mozambique’s trade has been able to function in a highly regularized fashion because the families at the top were allegedly able to build strong connections within the ruling party.

Like old-school kingpins, drug profits were laundered through largely empty beachfront hotels and a glitzy shopping mall in downtown Maputo. At its height, the kingpin families were even able to launder their money through government bonds, Hanlon alleges. The families came under scrutiny, however, when Mohamed Bachir Suleman was outed by a drug kingpin in a WikiLeaks cable, which was confirmed by former president Barack Obama in 2010.

Now, freelancers are disrupting that trade, thanks to WhatsApp and other messeaging services. Drugs are trafficked by drivers and fisherman who follow anonymous instructions from Dubai and United Arab Emirates, bypassing the traditional networks. Through encrypted apps like Telegram, Viber and Signal, dealers can send photos of the product and the contact person, making it easier to trust these-so-called freelancers. These could be fisherman bringing the heroin shipment ashore, or truck drivers looking to make extra money participating in the criminal gig economy.

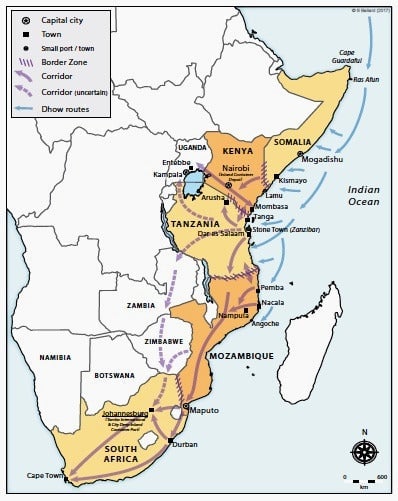

The heroin still travels to Mozambique in a rather old-fashioned way. Motorized dhows leave the Makran coast off Pakistan and Iran with heroin produced in Afghanistan. Usually no longer than 15 to 23 meters (49 to 75 feet), they are small enough to sail along on the Indian Ocean undetected by satellite or patrol vessels. If they are stopped, they pretend to be fishing vessels, with the drugs hidden in concealed compartments, according to the reports.

Pemba and the Quirimbas archipelago, usually associated with Mozambique’s idyllic tourist spots, are identified as landing areas for the drugs with calm waters and sand dunes that are good for hiding smugglers. Larger quantities of heroin arrive via container, packed with motorcycles and appliances from the Middle East or rice from Pakistan. A bribe is believed to be enough to avoid searching.

This new decentralized model, with its improved communication channels, allows traffickers to follow the “Latin American” model—choosing isolated routes. Improved mobile signals means kingpins can pass along the telephone number of a bribed official. So-called freelance drivers are given cash to bribe officials along the way and are paid through the bribing money that is left over, since little heroin actually stays in Mozambique.

Most of it is destined for Johannesburg, where it makes its way to the European market. Mozambique hardly has reports of successful raids, but evidence of the trade is uncovered by neighbors. In January, a Mozambican driver was arrested in neighboring Swaziland after being caught with 200 kilograms of heroin, while in June 2017 in another driver was arrested while trying to cross into South Africa with a similar amount.

It’s unclear, however, whether this disruption will be enough to dismantle Mozambique’s criminal network. While the criminal gig economy has created a parallel trade, it relies on the traditional corruption within the policing and the judicial system.