A Kenyan painter’s art questions China’s deepening reach in Africa

The officials in suits arrived uninvited at Michael Soi’s studio located in the fringes of the industrial area of Nairobi. They were four men and two women, Chinese, and instantly started rifling through the stacks of artwork in the space and tossing paint cans around.

The officials in suits arrived uninvited at Michael Soi’s studio located in the fringes of the industrial area of Nairobi. They were four men and two women, Chinese, and instantly started rifling through the stacks of artwork in the space and tossing paint cans around.

This was in 2015, a year during which China and Kenya were strengthening their bilateral relations with promises of working together in sectors as diverse as agriculture, infrastructural development, tourism, besides peace and security. Soi, a veteran artist known for his politically and culturally charged pieces, said the group started “lecturing” him, chiding him for being “ungrateful” for China’s contributions to Kenya. Soi immediately asked them to leave his space.

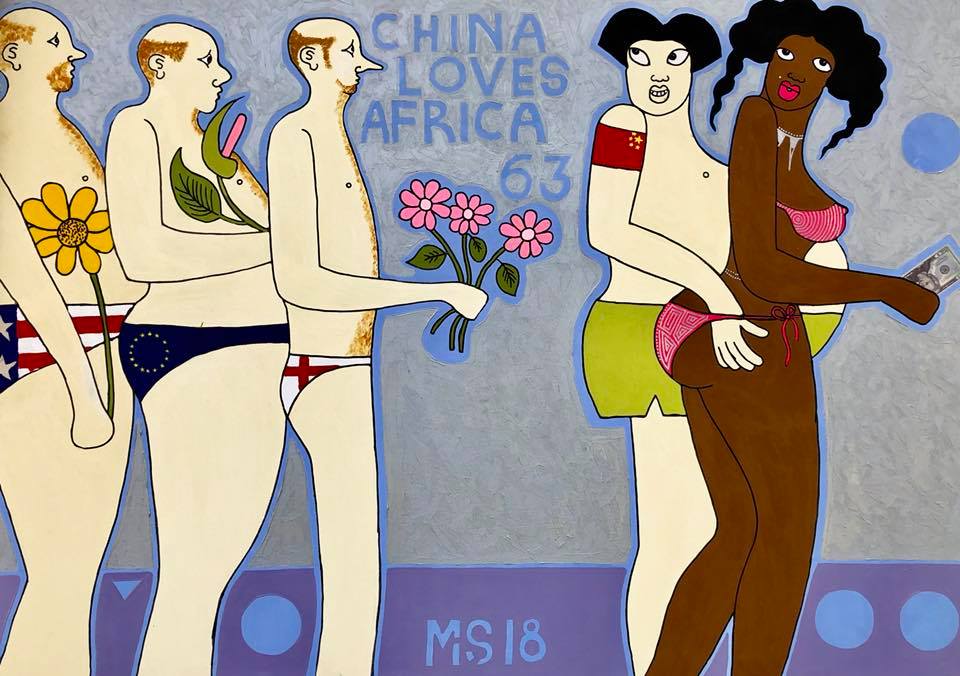

The work at the center of this peculiar visit was Soi’s “China Loves Africa” collection: an eclectic assortment of 74 bold visual pieces that continue to interrogate China’s place in Africa. As Sino-African relations have grown over the last decade, China’s diplomatic, trade, military, and soft power efforts have increasingly come into sharp focus. Previously furtive about its investments and moves, Chinese officials are also increasingly countering the narrative that its approach to Africa, as some critics say, is purely based on “chopsticks mercantilism.”

This has allowed artists like Soi, Kenyan political cartoonist Gado, and Ghanaian cartoonist Bright Tetteh Ackwerh the chance to use self-deprecating humor and ingenuity to question and prod the relationship between the two sides. “It’s a topic that leaves me with very many questions. And unfortunately, it’s not just happening in Kenya alone,” Soi says. “It’s basically African leaders mortgaging Africa to the Chinese.”

Soi’s acrylics on canvas paintings are sharply political and expressive, questioning Beijing’s push to making the most of Africa’s cheap labor, natural resources, and the continent’s increasing need for advanced technology and infrastructure. Put together, the pieces stand as both social commentary and a visual diary of how China is shaping the future of Kenya—and Africa—for generations to come.

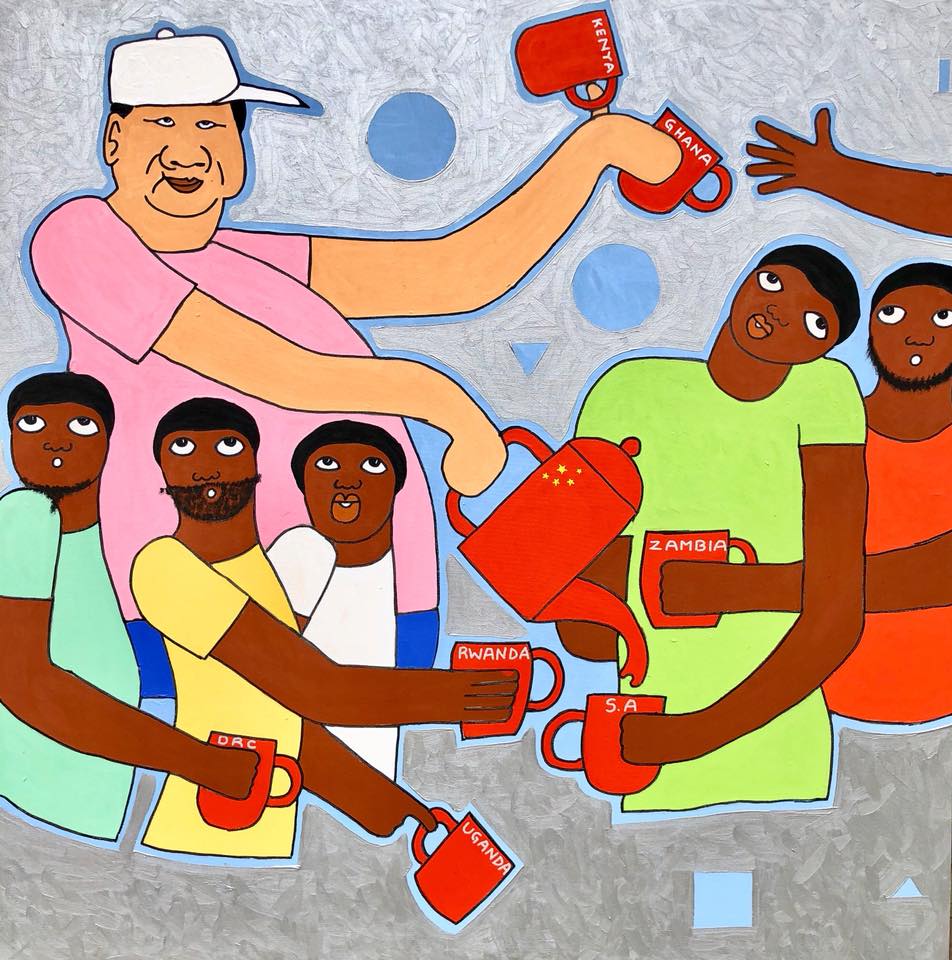

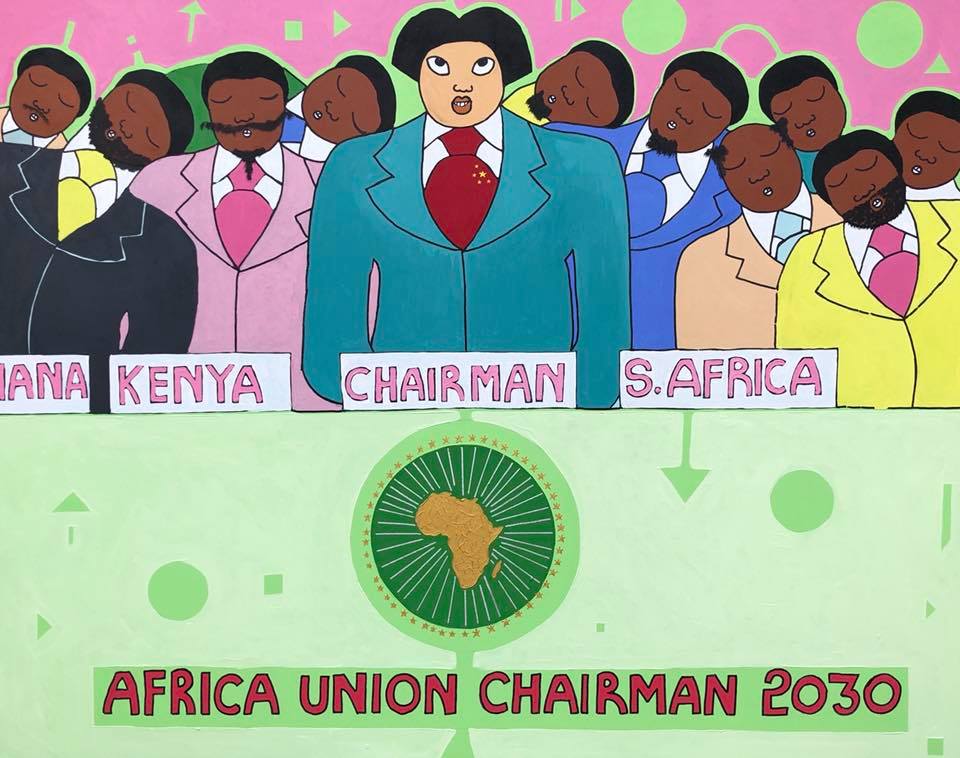

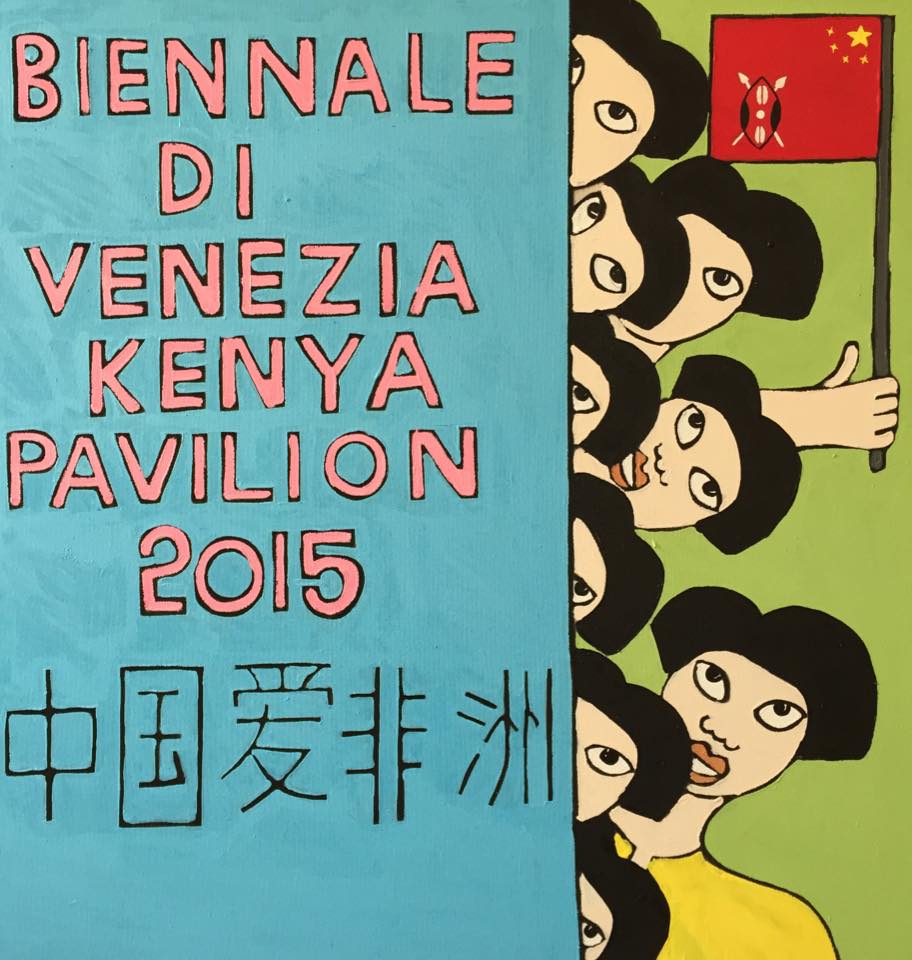

In one of the paintings, Soi, 46, expresses his frustration over Chinese artists representing Kenya at the Venice Biennale in 2015. In another, China is depicted as another global power that, like its European and Western predecessors, only takes from Africa, binds nations in debt, and doesn’t give back. Chinese president Xi Jinping, who just concluded a trip to Africa, appears in several illustrations too, dispensing largesse to countries including Rwanda and South Africa. Another piece zooms in on China’s relationship with the African Union—it built the body’s headquarters in Addis Ababa and was accused of spying on it—depicting a Chinese leader as its head by 2030.

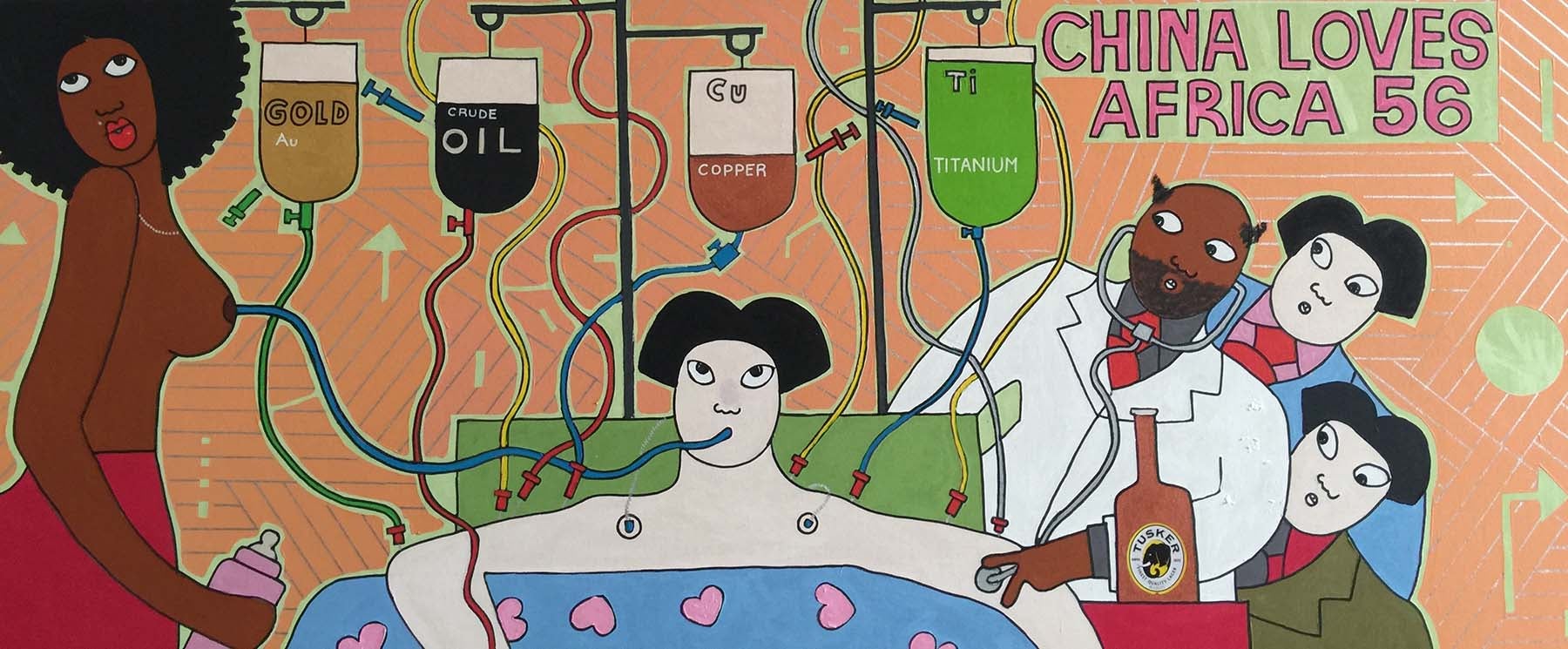

Soi also goes beyond the usual truisms in Sino-Africa relations to provoke and challenge onlookers. Using nude female portrayals, he shows Africa as a woman being lured by China away from other Western nations. In another piece, a black male doctor administers treatment intravenously to a bedridden Chinese man drawing energy from gold, oil, copper, and titanium drips hooked to a black woman.

One painting also mocks China’s contributions to Africa as meager by showing a group of men staring at a Chinese man’s manhood along with the words, “For Africa, small can still be beautiful.” Soi’s application of nudity across all his works has drawn criticism, with the National Museums of Kenya even banning them.

But he says creating conversations and dialogue around the flawed relationship with China constitutes the first step towards mending and balancing it. Otherwise, he warns, “It’s a story that will never end well for Africa.”