African governments’ quest for cheap electricity has kept millions of us in the dark

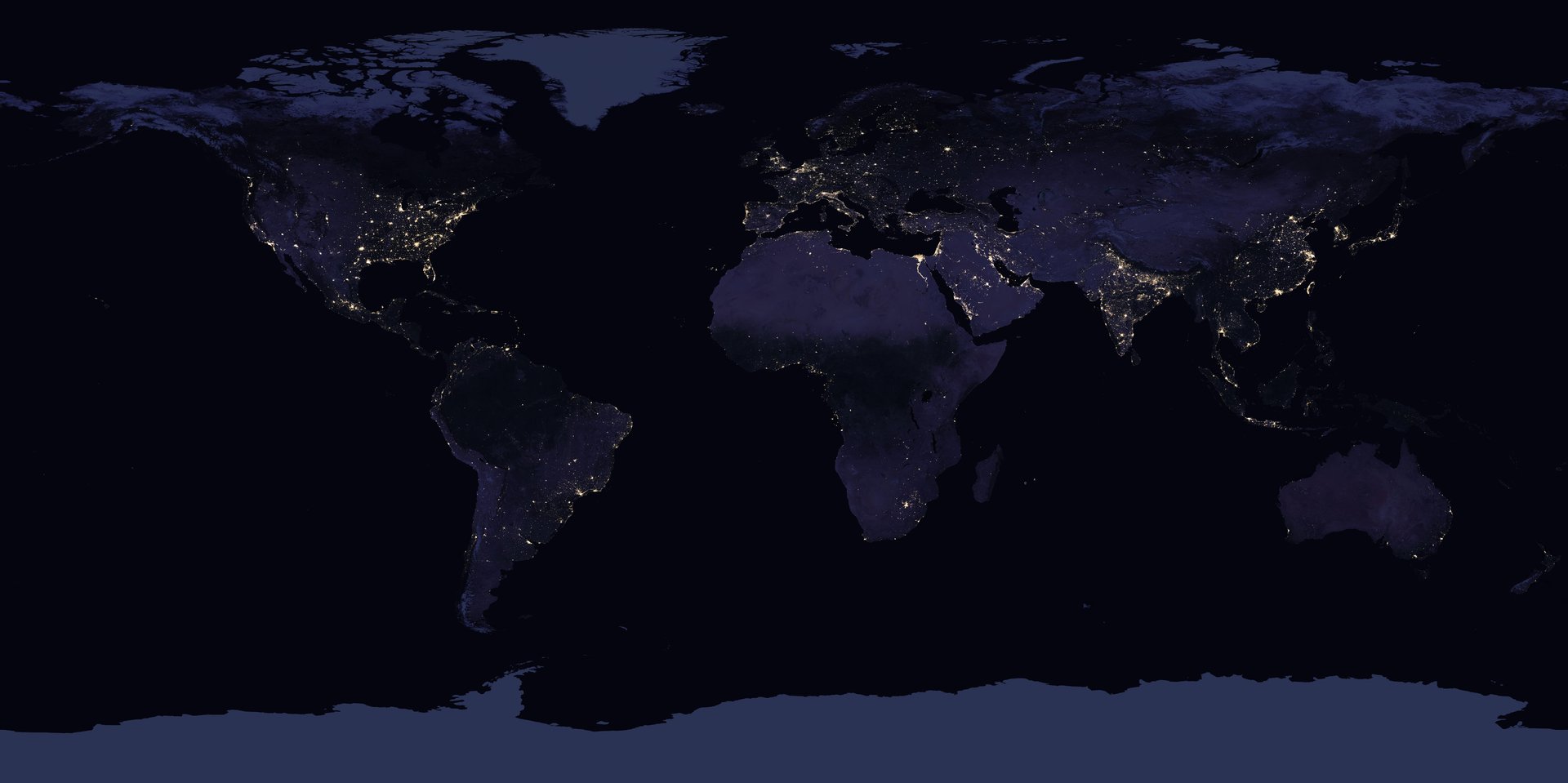

Most of us have seen the famous NASA composite photograph showing the world at night, which starkly highlights Africa as a truly “dark continent”. With an electrification rate of 42% in 2016, Africa lags all other regions in the world, with the lowest rates in rural areas, according to the World Bank (pdf, pg 49).

Most of us have seen the famous NASA composite photograph showing the world at night, which starkly highlights Africa as a truly “dark continent”. With an electrification rate of 42% in 2016, Africa lags all other regions in the world, with the lowest rates in rural areas, according to the World Bank (pdf, pg 49).

There are many reasons for this but I’d like to focus on African power utilities. Power utilities are a very important part of the chain for delivering electrical power to end users. One of their key roles is to purchase power that has been generated by others, sell it on to end-users and to collect revenues. They are vital for extending grid-based power to consumers and to ensure regular and efficient power supply. As they collect money from end-users and pay it on to other players in the system, they are also vital in ensuring money flows through the entire power sector.

The problem is that across Africa, the vast majority of the power utilities are effectively bankrupt. Another World Bank study (pdf) on African Utilities shows that only two of the 39 African utilities surveyed, in the Seychelles and Uganda, were able to generate enough cash to cover both their operating costs and capital expenditures necessary to invest in the maintenance and expansion of the grid. In fact, only 19 of the 39 companies were able to generate enough cash to cover their day-to-day operating costs. It means the rest were not even able to pay everyday costs, like salaries, in full.

Reality check

Power generation projects, which have to sell their power to these bankrupt utilities, require creative financing structures to get around these problems. In a bid to reduce their risk when financing these projects, bankers employ financial tools like put call options agreement or World Bank partial risk guarantees. The problem is these tools add complexity and cost which end up being passed on to the end-user or worsen the financial state of the power utility.

A lot of these financial structures ultimately boil down to being a form of government guarantee, which means that they can’t be scaled up to “solve” countries’ power problems because the governments cannot carry all the liabilities. Countries try to introduce the private sector into power generation precisely to reduce such guarantees, which then end up returning through the back door in the form of government support.

Ironically, technology can make the utilities’ problem worse, not better—at least in the short term. In the past, grids were developed because it was cheaper to generate large quantities of power and distribute it over wide distances, rather then generate smaller quantities closer to the place of use. It is for this reason that electricity is seen as a business that benefits from “economies of scale”.

Technology that now allows smaller quantities of power to be generated closer to the end-users at prices not too much higher than grid-based power are undermining those economies of scale. More efficient turbines, for example, allow large power users like cement plants and petrochemical factories to come off the grid. Today the limiting factor for large companies to come off the grid often isn’t the efficiency of the power generation technology, but the lack of easy availability of fuel, such as gas or coal to power these turbines Even this problem is being solved by innovations like mini-liquefied natural gas projects.

On the smaller end of the spectrum, technologies such as solar power and improved batteries are allowing commercial businesses like bank branches and petrol stations to also come off the grid. This may sound like a good thing, and it really is, but these trends mean African power utilities are beginning to lose their best customers.

This matters because grids are still the best way to provide power to high density urban areas where a lot of the poorest people live. Solar systems cannot provide enough power in dense environments can still be up to twice as expensive, even before taking storage into account.

Grids not only allow power to be sold far away from the place it is generated, but they also allow for the cross-subsidization of the poorest users by the more affluent ones, improving affordability especially in dense urban areas. Given the rapid urbanization across Africa today, this will only become more of a problem in the future.

Effectively bankrupt

Why are so many African power utilities effectively bankrupt? For one thing, they are incredibly inefficient. Efficiency can be improved by proper metering, investing in the system to reduce losses, improving collections and being able to cut off non-payers. This last one being easier if there is up-to-date metering and certain big players like government departments and military installations are also forced to obey the rules. These operational improvements and efficiencies will improve the supply of power but will not go far enough.

Which brings us to the crucial point: power tariffs. An improvement in the power situation in Africa cannot happen without an increase in power tariffs. Most power utilities are government-owned and where they aren’t, governments heavily regulate them. Regulators are thus able to impose pricing caps to ensure affordability.

While there is a very strong argument for providing cheap, subsidized power for the poorest in society, this should be done in a way that limits subsidies to the really deserving and the system as a whole needs to be able to charge tariffs that on average cover all costs. If this doesn’t happen then all manner of bad things will follow. As you might guess prices have been set too low by African governments. These subsidies have also been made too widely available, benefitting the elite and middle classes more than the poor (who, not having good access to the grid in the first place, don’t have ready access to these subsidies).

The outcome is rather predictable. The companies aren’t able to maintain their service levels, meaning that losses increase, leading to poorer services, and even more losses.

Of course there will also be no funds to expand the network, to provide more people with power, or to spend on increasing generating capacity for customers, whose electricity consumption tends to increase with time. This leads to even further declines in service quality, and more people coming off the system.

Perhaps governments think that they can fund the deficits from their budgets? Even if this is possible when the subsidies are first introduced, increasing demand from growing populations will make this unsustainable very quickly. The end result is a bunch of zombie utilities and millions of Africans in the dark who shouldn’t be.

Put the lights on

What can be done about this?

The World Bank suggests focusing on increasing efficiency, which should lead to improved service quality. This should make the inevitable tariff increases more palatable to the paying public. Such tariff increases would best be implemented in small increments over time, rather than all at once, to make them more digestible.

Technology also provides a long-term answer, even if it contributes to the problem in the short-term, as described earlier. As renewable power and storage technologies become cheaper and more efficient they will gradually allow for the implementation of cheaper mini-grids and smart grids, increasingly within the reach of the really poor, even in urban areas. Perhaps, grids will one day become marketplaces allowing people to sell excess power from their solar installations to those who have a need for power at that time. Prices can be set dynamically to allow supply to match demand.

That however is for the future. Today governments need to bite the bullet, make some bold, hard and potentially unpopular choices if they want to increase the long-term welfare of their citizens..