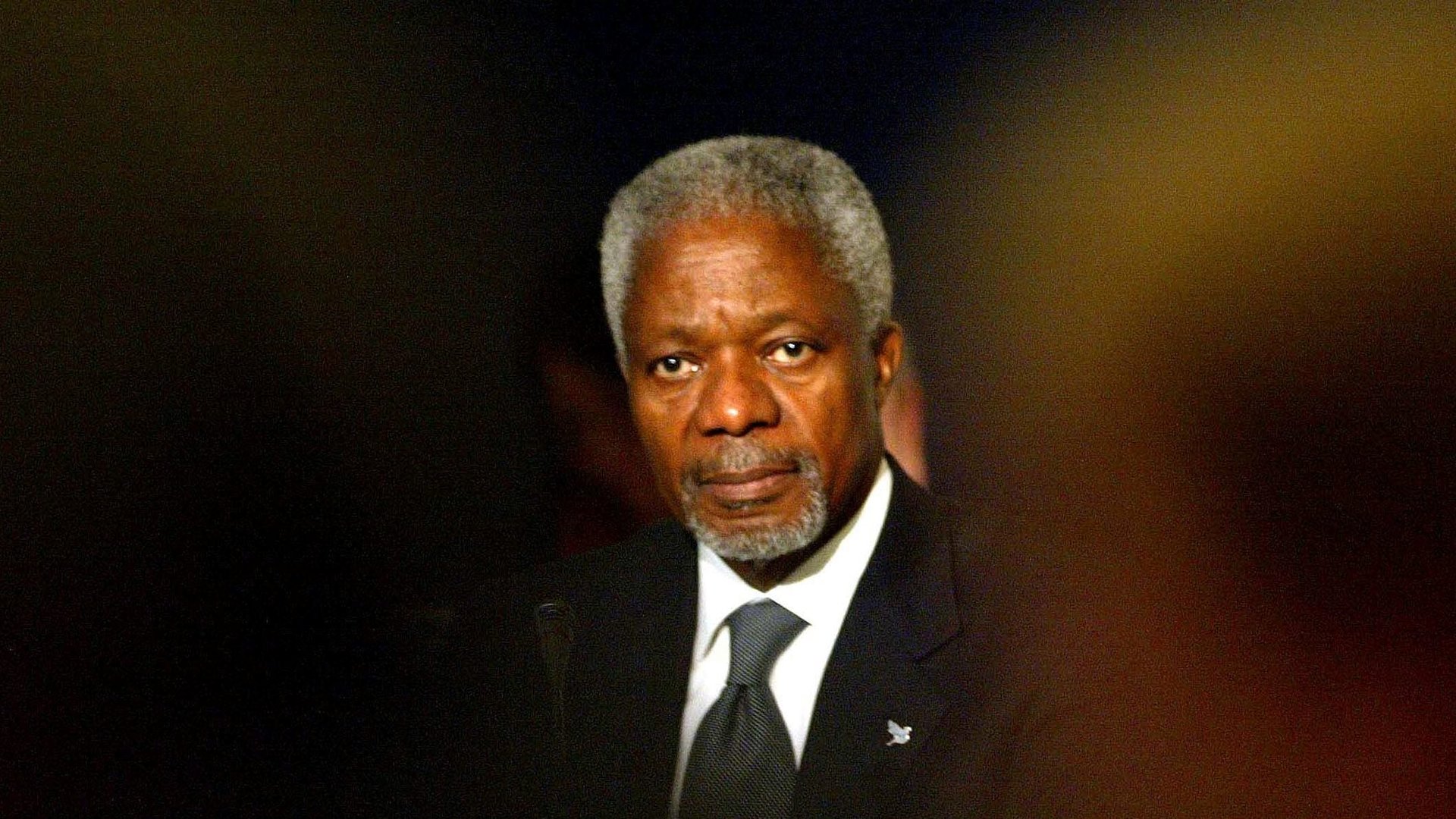

Kofi Annan, the African leader who reshaped the UN, has died

Kofi Annan, the former United Nations secretary-general and Nobel peace prize winner, died today (Aug. 18) at the age of 80. His family confirmed that he passed away at a hospital in Switzerland “after a short illness.”

Kofi Annan, the former United Nations secretary-general and Nobel peace prize winner, died today (Aug. 18) at the age of 80. His family confirmed that he passed away at a hospital in Switzerland “after a short illness.”

The Ghanaian diplomat led the UN from 1997 to 2006. He was its seventh secretary-general, the first black African in the position, and the first in this role to be selected from the ranks of the global agency’s staff. During his tenure, Annan worked to mediate conflicts all over the world. He established several key UN initiatives that pushed for human rights and sustainable development. He also reformed the UN’s peacekeeping, human rights protection, and counterterrorism efforts.

As news of his death spread, Annan was remembered by many as a champion for peace and global prosperity, including the current secretary-general António Guterres.

Annan was born in Kumasi, Ghana in 1938. He joined the UN in 1962, working in the fields of human resources management, health, budget and finance, and peacekeeping.

Under his leadership, the UN’s place in the modern world was reaffirmed. One of his landmark proposals led to the creation of the Millennium Development Goals, which aimed to eradicate extreme poverty, combat malaria and HIV/Aids, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, and more.

Annan considered the establishments of these goals one of his greatest achievements as secretary-general, because they compelled global leaders to actively fight poverty and reduce global inequality. One of his greatest regrets, he said, was not stopping the US-led war on Iraq in 2003, which he called illegal and a breach of the UN’s founding charter at the time.

Annan’s also oversaw in 2005 the creation of two vital intergovernmental bodies: The Peacebuilding Commission and the Human Rights Council. In an increasingly interdependent yet volatile world, the two agencies were created to support peace while promoting and protecting human rights.

Annan’s tenure at the UN was not without reproach. As the under secretary-general for peacekeeping in the mid-90s he was criticized for the ineffectiveness of peacekeeping efforts during the Rwanda and Srebrenica genocides. Towards the end of his time as secretary-general, his son was reported to be part a scandal involving the UN’s oil-for-food program in Iraq. His son was also named in the Panama Papers, which revealed the secretive offshore accounts of the world’s rich.

Annan was succeeded by South Korea’s Ban Ki-moon. He went on to establish the Kofi Annan Foundation and serve as chair of The Elders, a group founded by Nelson Mandela. He promoted peace and dialogue across Africa, most critically during Kenya’s post-election violence in 2008.

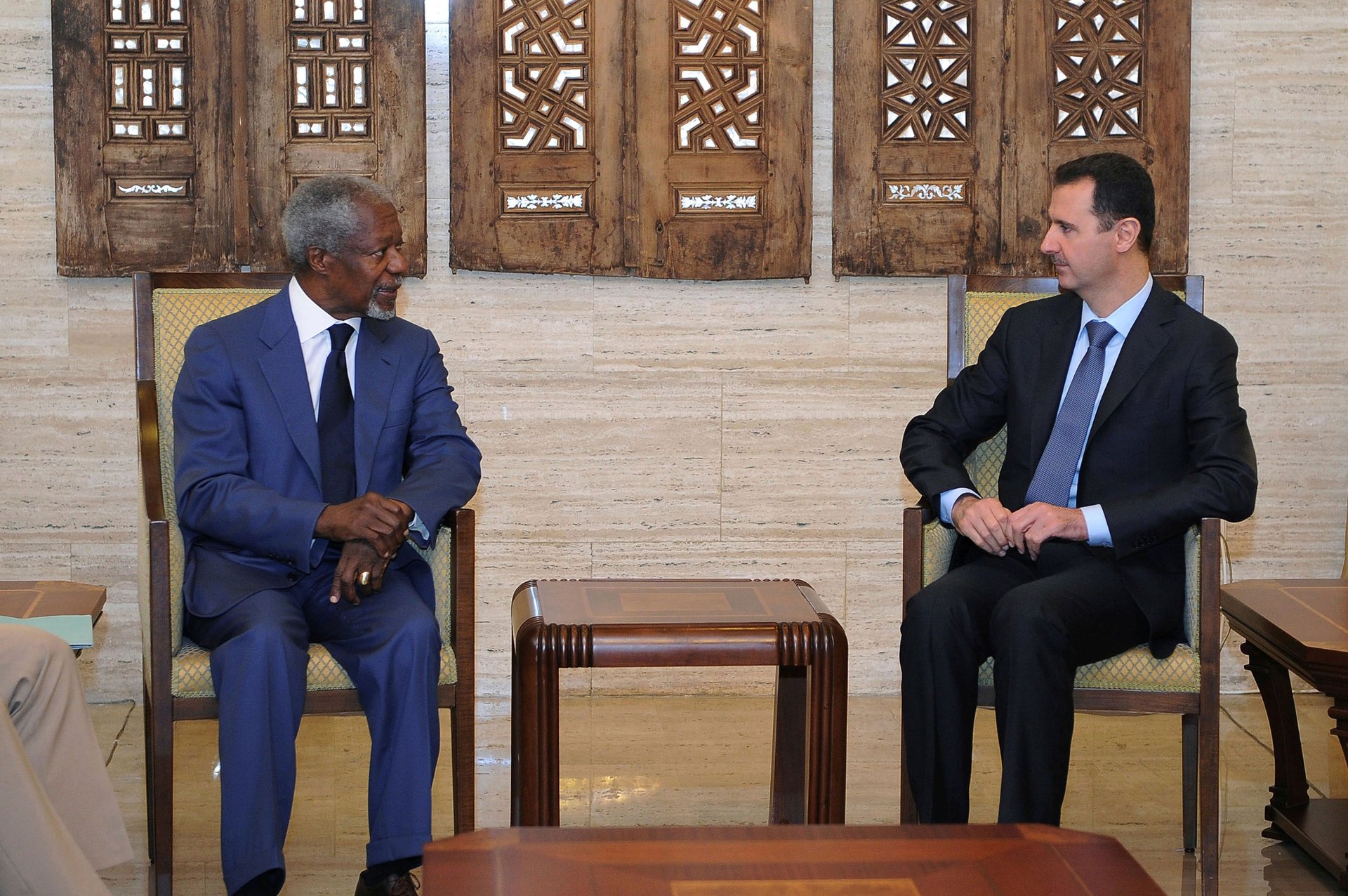

Annan also served as a special envoy for Syria early on in the war. He resigned from that post after five months in 2012 citing “finger-pointing and name-calling” among global leaders, a decision that forewarned of the political impasse that was to follow.

Over the last year, Annan had expressed concern over the state of global leadership. In April, he told the BBC “cool heads and sober judgment” are needed to tackle the world’s conflicts. “We cannot allow situations where leaders threaten war on television or on Twitter,” he said.

”Many people in economically precarious situations are seduced by the siren songs of cynical populists,” he wrote for Quartz in May.

In 2001, the Nobel Committee awarded Annan and the UN its coveted peace prize for helping make the world a safer and better place. Annan was recognized for his efforts to restructure the UN and focus it on human rights.

“He was an ardent believer in the capacity of the Ghanaian to chart his or her own course onto the path of progress and prosperity,” writes Ghanaian president Nana Akufo-Addo. “His was a life well lived.”