China is generous in promising billions to Africa but is tough in redeeming pledges

The third summit of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) opens today (Sept. 3) in Beijing. Over 40 African heads of states and governments—save for eSwatini which still holds out in recognizing Taiwan over Mainland China—are already in the city with a coterie of advisors and brokers eager to lobby for a share of the Chinese largesse in prospect.

The third summit of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) opens today (Sept. 3) in Beijing. Over 40 African heads of states and governments—save for eSwatini which still holds out in recognizing Taiwan over Mainland China—are already in the city with a coterie of advisors and brokers eager to lobby for a share of the Chinese largesse in prospect.

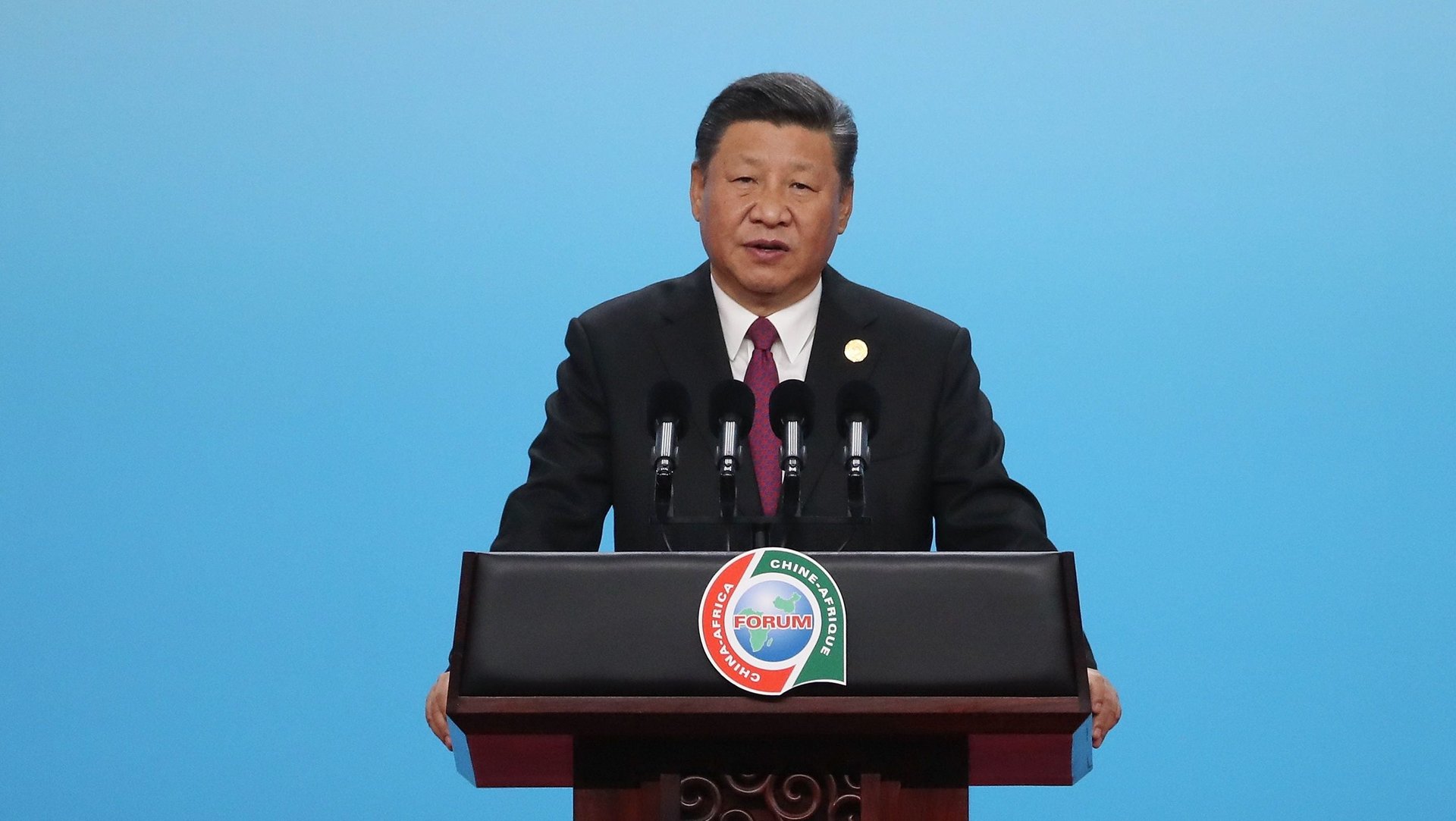

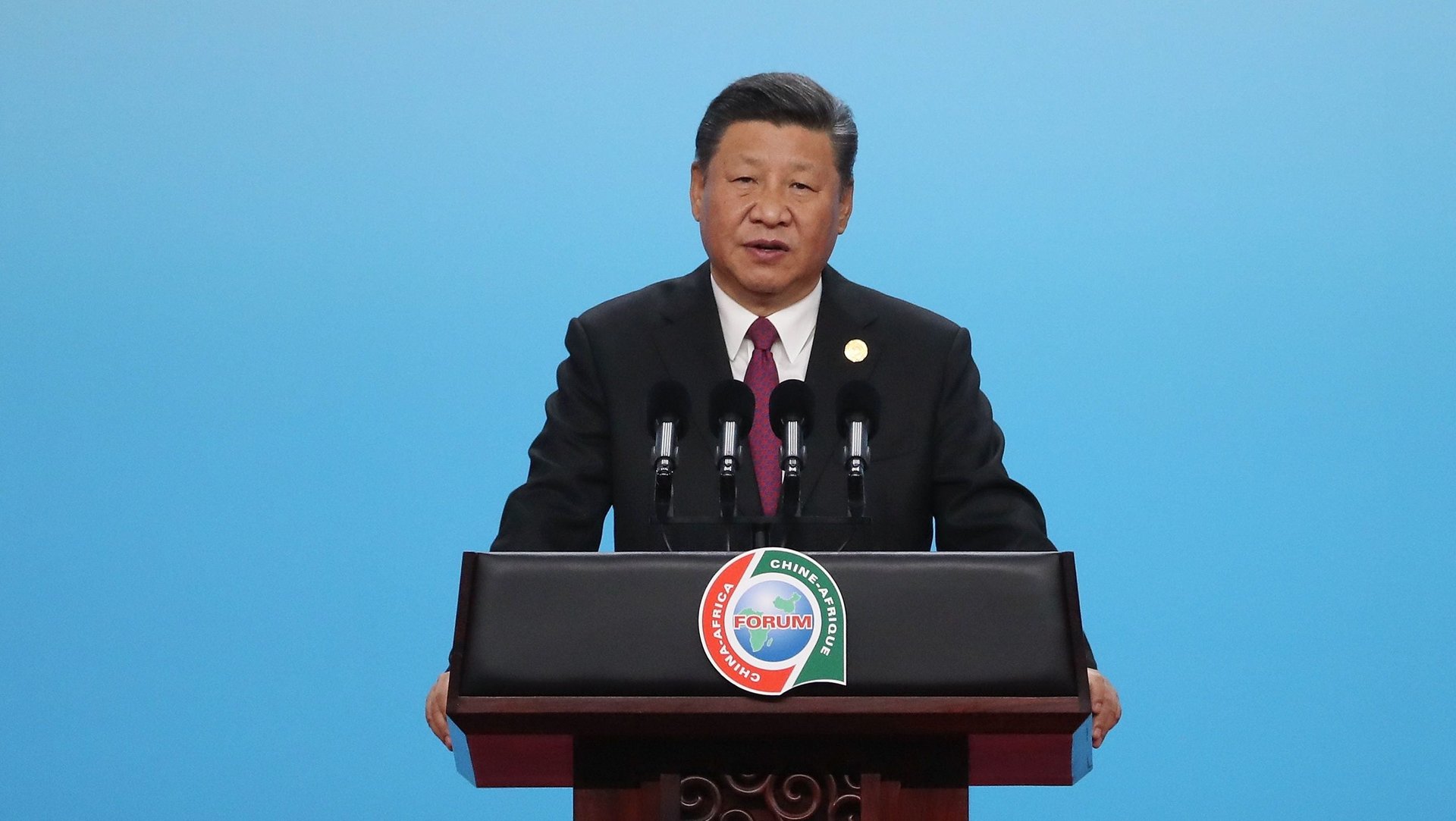

When the summit was first announced earlier this year, the intention was for it to be co-chaired by presidents Xi Jinping of China and Jacob Zuma of South Africa. But with the latter resigning from office in February, the former will open the conference alone and reaffirm the commitments made in 2015 in Johannesburg.

Over the years, commentators have focused on only one key message amidst the effusions of goodwill: the financial pledges by China to Africa. Three years ago, the headline number was $60 billion, to be released over three years, via a plethora of vehicles and initiatives. About $45 billion of those funds have come through, most of them to a very small group of nations. Curiously, less than $10 billion of this amount is classified as “foreign direct investment,” with the overwhelming proportion being in the form of sovereign-backed, natural resource, securitized loans.

No doubt, many billions of dollars of pledges shall be made before the close of this week. Ghana has already announced ratification of the first tranche of $2 billion, out of a promised $19 billion, in the weekend before the summit. All this, even as the country, like the great majority of African nations, continues to pursue deals announced more than a decade ago—a situation likely to leave many analysts new to the context baffled.

Tough dealmaking

The Zimbabwean and Ghanaian situations are quite instructive.

Pledges from China’s intricate web of state and quasi-state economic diplomacy actors to Zimbabwe have totaled over $33 billion in the last two decades, including a massive $6 billion package concluded in Dec. 2015.

Over the last five years, in particular, a long list of projects have been identified as “bankable” by the Zimbabweans and included in various technical and cooperation agreements signed with the Chinese, adding up to the pile of unredeemed pledges. They range from the $153 million upgrade of the Robert Mugabe International Airport and the $1.4 billion Hwange coal-fired power plant to the University of Zimbabwe’s supercomputing cluster. Yet, from all these amounts, less than $2.5 billion has actually been released to Zimbabwe to date.

Ghana has been even more successful in securing fat Chinese pledges. Over the last two decades, the country has secured commitments to the tune of over $60 billion. Former president John Atta-Mills, for instance, during a state visit to China in September 2010, signed agreements worth more than $15 billion. To date, Ghana has received about $3.5 billion from China.

Part of the problem, as the John Hopkins scholar Deborah Brautigam has long emphasized, is the frequent conflation of a wide range of agreement and memoranda forms, where China-Africa state-driven dealmaking is concerned, across a wide spectrum of definitiveness. Export credits and guarantees, co-venture activities and project advances besides securitized facilities all end up in the same soup as grants and “policy loans.” Chinese dealmakers have developed a truly elaborate and sophisticated matrix of engagement archetypes that capture everything from mere “letters of intent” to ironclad project loan agreements.

Furthermore, China’s model of economic diplomacy requires that even pure private initiatives involving non-state actors in China typically gets bundled up with government-to-government undertakings, receive official sanction during state visit banquets, and require as counter-parties on the African side only government agencies, ministries or state-owned enterprises. Many an African private operator has been shocked to discover that their counterparts in the Chinese private sector won’t move a muscle, after the flashy signing ceremony in Beijing, unless the former can bring their governments to the table.

Of greater consequence than all the above though is the Chinese focus on projects that can self-collateralize based on tangible outputs with strong Chinese market demand. That is why Angola has to date redeemed more than $45 billion of the roughly $60 billion of loan commitments made over the last two decades by China. Petroleum-related lending alone exceeds $22 billion. In 2015, Angola’s state oil company Sonangol, became almost entirely dependent on China’s Development Bank (CDB) to finance its overdrafts. It realigned shipment schedules to keep the tap flowing. When fiscal pressures made facility servicing increasingly difficult, China dispatched crack analysts to Luanda to help Sonangol restructure its credit accounts and reopen credit lines.

Contrast this with the sorry case of Harare’s municipal authorities, who have been asked to repay more than $70 million lent by the Chinese for clean water distribution projects ahead of term expiration. This came after China revoked a $143 million facility due to poor project management. Ghana’s 2012 $3 billion CDB facility was likewise partially frozen after the country bungled post-execution drawdown, leading to only one project, a gas processing plant, being financed.

In sum, China is generous in its promises but tough in its dispensing. Most African bureaucrats and technocrats refuse to spend time and effort understanding the myriads of factors influencing the unlocking of pledged funds from China. Instead, they simply concoct new schemes when old ones fail to fly. By so doing, they have specialized in the inflation of hopes than in the closing of deals.