South Africa won’t become less violent until it’s more equal

The release of crime statistics in South Africa always triggers great angst among ordinary citizens, and obfuscation on the part of the South African authorities. This year was no exception.

The release of crime statistics in South Africa always triggers great angst among ordinary citizens, and obfuscation on the part of the South African authorities. This year was no exception.

In their latest release of crime statistics, the South African Police Service seem to have tried to downplay crime rate increases (and exaggerate crime rate decreases), by using the wrong population estimates. The police incorrectly used the June 2018 population estimates in their analysis of the 2017/18 crime rates. This is not the first time they have made this kind of bungle.

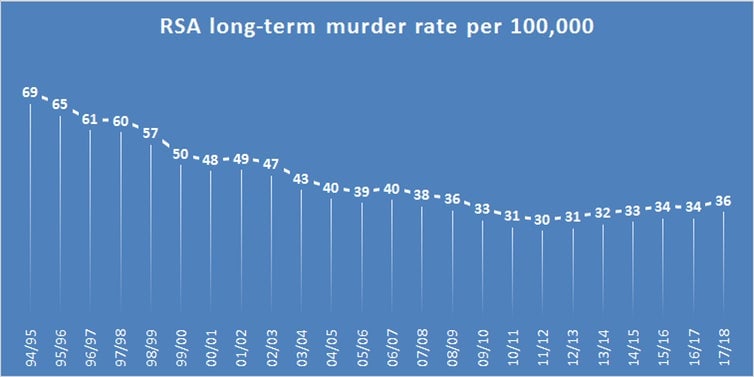

But their motivation is clear. Applying the correct population estimates suggests that the country saw the biggest per capita annual murder rate increase since 1994. Last year’s figures suggested that the murder rate had stabilized. But these were unfounded, as the murder rate has now risen to 36 per 100,000. The last time it was this high was in 2009. The increase is cause for serious concern.

Even the new minister of police Bheki Cele expressed shock at the numbers, describing South Africa as being close to a “war zone”. He admitted that the country’s police force “dropped the ball”.

A logical response might be that there is a need for more policing. According to Cele: “We have lost the UN norm of policing which says one policeman to 220 citizens. One police officer is now looking at almost double that.”

But this isn’t the answer. A sensible response to South Africa’s rising crime rates would be twofold: a problem-solving approach that would require a close analysis of what’s causing crime to rise in a given area. Then they’d need to devise a plan that takes into account all the contributory factors—and involves everyone affected in addressing it.

And, secondly, the country’s leaders must address inequality. South Africa is a highly unequal society. It has one of the highest gini-co-efficients (a measure of inequality) in the world. Research shows that inequality and crime go hand in hand.

The question of police numbers

Police leaders reported that their staff numbers have gone down by 10,000 since 2010. They argued that they had 62,000 fewer police than were needed.

Police agencies all over the world often claim that, to reduce crime, they need bigger budgets and more officers. But the evidence that these two things automatically lead to more effective crime prevention is far from clear.

Take the issue of police numbers. Short-term and extreme spikes in police numbers (such as in response to terrorist threats) do seem to reduce crime. But a review of a number of studies on the relationship between policing levels and crime rates suggested that the impact of more police is generally small. The paper also noted that part of the problem was that there have been few rigorous experiments on, for example, extra police resources being allocated randomly.

Bigger budgets also have mixed outcomes. This is because, very often, a significant proportion of spending on police is ineffectual. Police resources often aren’t targeted, even though there’s evidence that doing so produces good results.

This isn’t hard to do: crime is highly concentrated in hot spots that are often surprisingly small and quite stable over time. With the right focus, resources could be directed to these areas. But mostly they aren’t.

Targeted approach

What works best is a problem-solving approach. This involves focusing narrowly on understanding specific crime problems in specific places, and using not only police but drawing on the knowledge and resources of all parties, including other government departments and local communities.

For example, particular factors might be contributing to a spike in robberies in a particular area. These could include a large cohort of bored young people in the community, paths that are fertile ground for attacks because they are dark and overgrown, or unlit parks near a derelict building.

More police patrols wouldn’t necessarily be the best solution. The underlying problems would need to be addressed. This might include creating a partnership between property owners, the agencies in charge of parks and lighting administration, schools and parents, and the communities that use the spaces.

One concern with a targeted approach is that crime is simply pushed elsewhere. But evidence suggests that the displacement effect is usually limited and that, in fact, nearby areas often enjoy a diffusion of benefits.

Inequality

There’s a more fundamental problem that needs to be solved on a national scale before South Africa’s crime levels can be reduced: inequality.

Research shows that inequality is arguably the single best predictor of whether a country will experience high or low levels of crime and violence. Inequality

- makes property crime more attractive and profitable;

- drives frustration, hostility and hopelessness; and,

- undermines trust, community engagement and the functioning of social and institutional structures.

South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world.

Where to from here

Murder levels nationally have been at about this level or higher (above 30 per 100,000, which is considered very high by global standards) since at least the 1970s. High levels of violence are not a matter of police resources. They are a structural feature of this society.

This is not to say that the police are blameless. Among other things they should be doing more to solve cases. But addressing the key drivers of crime and violence requires that South Africa builds a much larger social partnership. It has no hope of becoming a fundamentally less violent country until it becomes a more equal one.

Anine Kriegler, Researcher and Doctoral Candidate in Criminology, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.