No, China is not taking over Zambia’s national electricity supplier. Not yet, anyway.

On the wall leading into the Sikale Wood Manufacturers in Lusaka’s industrial outskirts, there is a freshly painted sign that reads: “We shall make Good Furniture, at a profit if we can, at a loss if we must, but always Good Furniture.” It was painted only a day earlier, in anticipation of a visit by Chinese and Zambian businessmen looking for new deals between their two countries.

On the wall leading into the Sikale Wood Manufacturers in Lusaka’s industrial outskirts, there is a freshly painted sign that reads: “We shall make Good Furniture, at a profit if we can, at a loss if we must, but always Good Furniture.” It was painted only a day earlier, in anticipation of a visit by Chinese and Zambian businessmen looking for new deals between their two countries.

The slogan is an idealistic take on the increasingly tenuous relationship between the Asian giant and the landlocked African country, which has now become test for China in Africa after it seemed that Zambia’s rising debt would lead to Chinese control of the national power supplier.

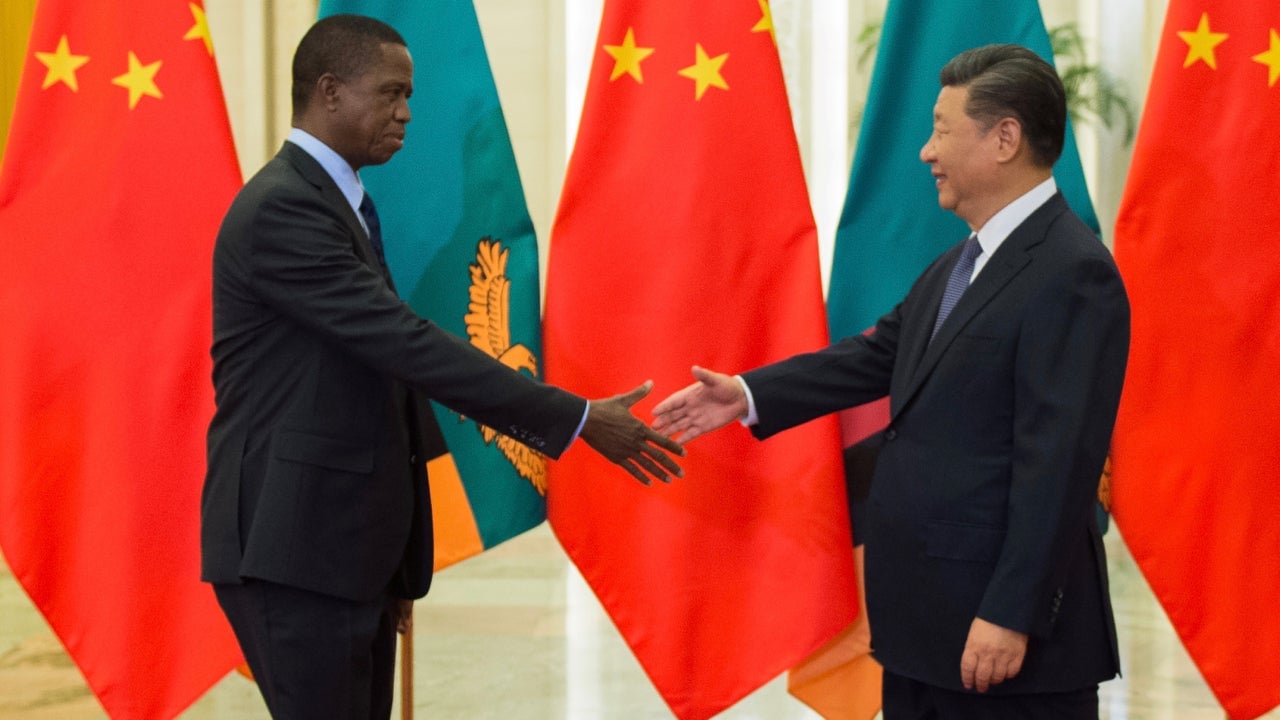

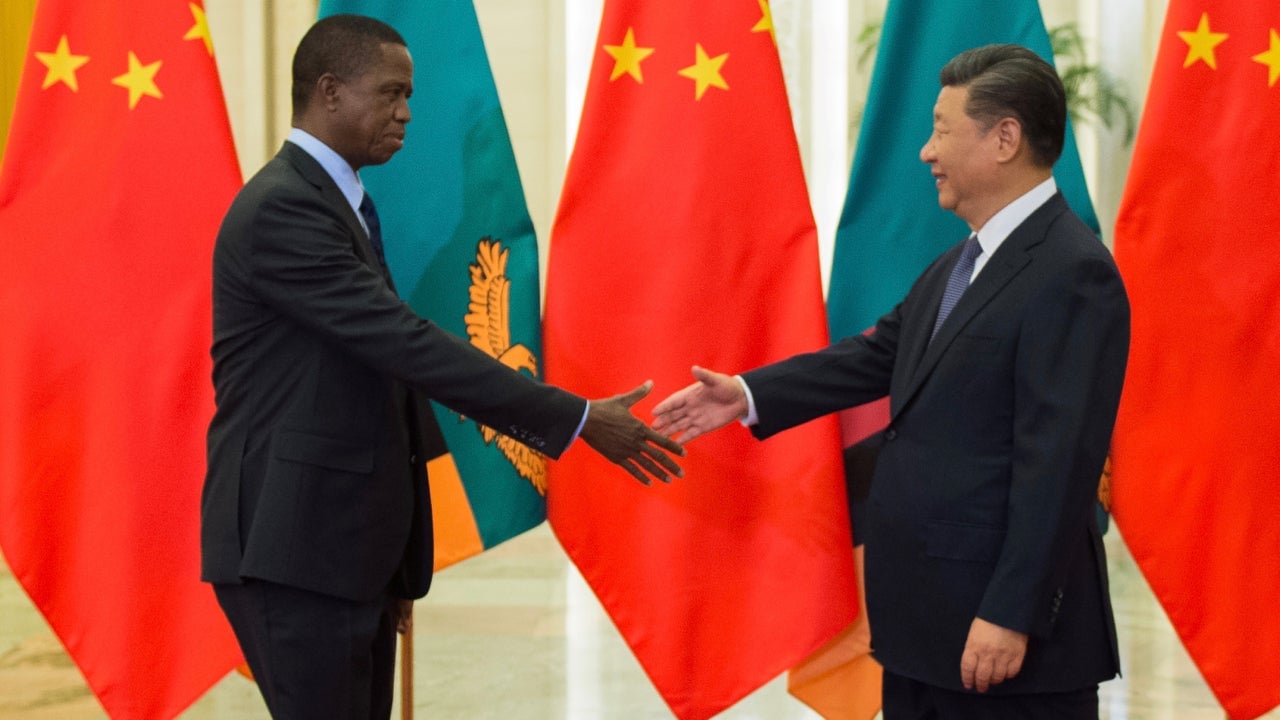

As commodities slumped, the copper producer looked elsewhere to stimulate its economy, borrowing from the east and the west. In July, bailout talks with the IMF reportedly stalled even as its finances worsened. After Zambian president Edgar Lungu returned from the Forum on China Africa-Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing, rumors started circulating that Zambia was now negotiating a new loan, with the national electricity supplier, Zesco, as a guarantee.

Although denied by the government, the possibility of China owning a Zambian state company became a cautionary tale in the ongoing story between China and Africa. Analysts saw the handing over of state assets as a result of the unbridled lending and borrowing between China and African states that has characterized the One Belt One Road policy. In the same week that the disputed story broke, the furniture factory was used as the best example of Chinese interests in Africa.

China-in-Zambia

“I built it slowly, slowly,” said managing director and owner Liu Ruumin. Liu came to Zambia more than 20 years ago as an employee of a state construction company. After three years he quit to start his own business as a timber exporter to China, which has now evolved into a furniture manufacturer with 300 employees on the factory floor, four stores in Lusaka and two more in northeastern cities of Kitwe and Ndola.

“Lots of Chinese, when they come from China, their impression is there is opportunity to make money easy….China is much more competitive,” said Liu. “But because that’s the impression that they have, sometimes people make mistakes. They tried to make money through shortcuts. They forget that there’s no free lunch.”

Zambia, seemingly eager to invite the Chinese to lunch, hosted the Partnership for Investment and Growth in Africa on Sept. 13-14 after the two-day World Export Development Forum. While the forum held by the International Trade Centre invited delegates from around the continent and the world, the forum was specifically for the Chinese. A representative of the United Kingdom’s influential department for international development (DfID) was there too, but perhaps tellingly, local journalists wandered off during his presentation.

Chinese businessmen who had been successful in Zambia were invited to extol the virtues of the country’s agricultural and tourism resources, and the advantages of a young population. Then they visited successful companies around Lusaka, including Sikale and the Zambia-China Cooperation Zone, a business park of small factories specializing in goods like shoes and mushrooms. This economic zone is one of the five in Africa that China announced in 2006, which are meant to foster growth in the host country, while making it easier for Chinese companies to set up shop, by reducing operational costs, as they evolve from provincial players into multinationals. It has facilitated, for example, the building of the new curved glass wing of the ageing Kenneth Kaunda International Airport by the Jiangxi construction company.

These deals have allowed China access to the country’s national resources, like the timber used by Sikale factory. An estimated one third of Chinese loans are secured by commodities, even as the West and Japan abandon this model of lending, according to a recent report by the Centre for Trade Policy and Development.

The report on Zambia’s growing indebtedness to China tries to make sense of the unequal relationship between China and Zambia and how the country has come to represent a cautionary tale on China-in-Africa, and what led to the national confusion and international admonition of Chinese lending to Africa.

The problem is that the extent of Zambia’s debt is unclear, and without clear figures the public conversation in Lusaka and beyond veers from hysteria to unperturbed.

“There’s nothing like that,” minister of commerce, trade and industry Christopher Bwalya Yaluma told Quartz at the forum. “I’d be the first person to secure you an appointment with the minister of finance and if you can’t believe me I will secure you an appointment with the president.”

Yaluma was minister of mines, energy and water development when many of the loans were first negotiated. While he concedes that Zesco, as a state asset is used a guarantee, but says as Zambia has never defaulted on a loan, the government has no fear of defaulting and losing Zesco.

“Why would we go and trade in Zesco? Does it make business sense?” he said. “And if we default, we’d go in for some other arrangements, it’s not that they can take our own asset. That is a key asset.”

While it’s true that Zambia has never defaulted on a loan, economist Trevor Simumba is concerned by the lack of political will shown by the Zambian government to manage its debt. The government has called for austerity measures yet in July, the finance ministry asked for an additional 7.2 billion kwacha (over $666 million) supplementary budget, reallocating funds for debt and the completion of infrastructure projects.

One of these projects is the Kafue Gorge hydropower plant that would supply Zesco with an additional 750MW and built by Sinohydro, a Chinese company. When Zambia struggled to come up with the initial capital, the Chinese company had to raise the funds through private channels, says Simumbe. That means the money need not flow through the treasury, which in turn means the terms of the loan are unclear to the public. It is now believed the Zambian government is negotiating with the Export-Import Bank of China to complete the project, after IMF talks stalled. The lack of transparency in the negotiations is fueling fears, says Simumba.

Sold out to the Chinese?

“We’ve been sold by PF,” read the pro-opposition newspaper, News Diggers on Monday Sept. 10, after the reports first surfaced that the national power supplier could be taken over by the Chinese. The call was made by several civil society groups and the opposition party National Democratic Congress, criticizing the ruling Patriotic Front party for reckless borrowing from China and accusing party members of misusing funds. The government’s denials did little to quell their anxiety.

The Patriotic Front has in turn used its channels to push the message that debt is necessary for development, speaking at churches, the state broadcaster and pro-government newspapers.

“It is not a waste when we build roads to ease the lives of people and give them opportunities,” government spokeswoman and communications minister Dora Siliya told the Zambia Daily Mail in a report on Sept 13. “The people in villages were able to watch television because of the Chinese. Even this building [the government complex] we are in is a witness of the Chinese money.”

Yet, even as the Zambian government points to huge construction projects as evidence of development—and the need for debt—last year’s budget only had 23% left of domestic revenue after paying its debt and public servants’ salaries.

It’s easy to see why Zambia’s debt has been politicized. When the Patriotic Front took over in 2011, external debt stood at 15% of the GDP, but by June, it had risen to 34.2%, according to the report by the Centre for Trade Policy and Development. Zambia’s debt is expected to rise to 60% of its GDP by the end of the year, compared to 35.6% in 2014, with the debt burden at more than 28% of national expenditure.

With Eurobonds due in 2022 and 2027 (with the first payment of $750 million) and talks with the IMF over a possible bailout suspended, there are concerns that Zambia may face a similar crisis of ill-disciplined debt as Mozambique did in 2017. Zambia, however, is already its own cautionary tale, having nearly drowned in its debt in the early 1990s and 2000s.

Just over a decade ago, Zambia was one of several countries who had their debt written off by the World Bank and the IMF. Now that lesson seems forgotten. It would be hard for any developing country to resist a Chinese loan: they’re relatively cheap, easy to access and come with fewer strings attached. At least, that’s the way it has seemed, until now.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox