We need to talk frankly about our rapid population growth in Africa if we want to beat poverty

I think about the future of my continent in terms of three questions: Are Africans healthy? Do they have access to a good education? And do they have opportunities to apply their skills?

I think about the future of my continent in terms of three questions: Are Africans healthy? Do they have access to a good education? And do they have opportunities to apply their skills?

Millions more Africans have been able to answer yes to these questions in recent years. But there’s an elephant in the room. One of the keys to keeping this progress going is slowing down the rapid rates of population growth in parts of the continent. But population issues are so difficult to talk about that the development community has been ignoring them for years.

Population growth is a controversial topic because, in the not-too-distant past, some countries tried to control population growth with abusive, coercive policies, including forced sterilization. Now, human rights are again at the centre of the discussion about family planning, where they belong. But as part of repairing the wounds created by this history, population was removed from the development vocabulary altogether. For the sake of Africa’s future, we should bring it back. Based on current trends, Africa as a whole is projected to double in size by 2050. Between 2050 and 2100, according to the United Nations, it could almost double again. In that case, the continent would have to quadruple its efforts just to maintain the current level of investment in health and education, which is too low already.

But if the rate of population growth slows down there will be more resources to invest in each African’s health, education, and opportunity – in other words, in a good life.

To be very clear: the goal of family planning programs is not to hit population targets; on the contrary, it’s to empower women so that they can exercise their fundamental right to choose the number of children they will have, when, and with whom. Fortunately, empowering couples to make decisions about their lives also improves Africa’s future by changing the population growth scenario across the continent.

Scenarios

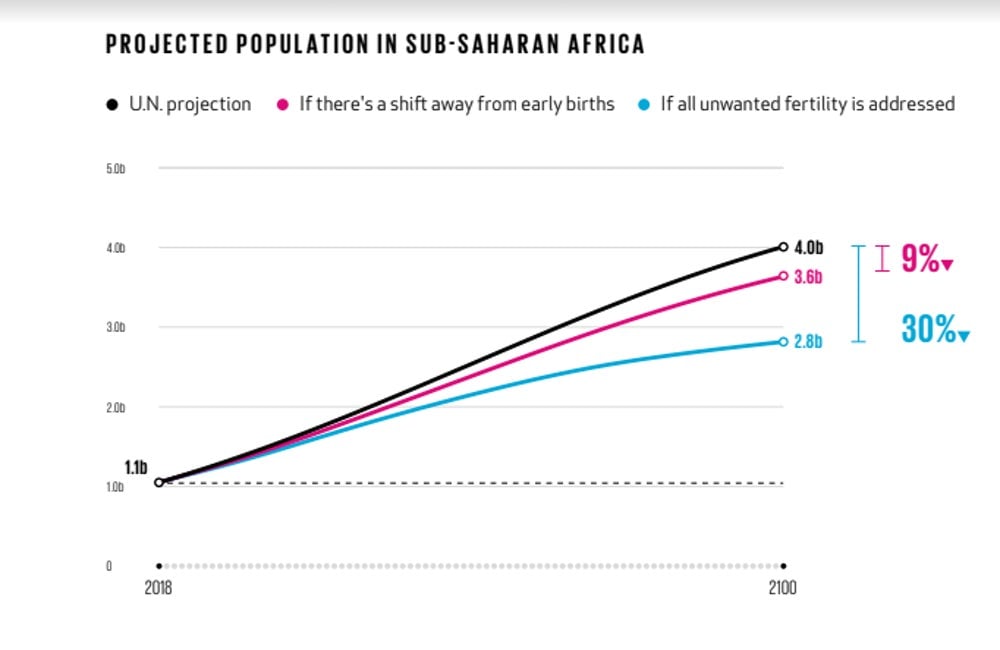

Some relatively simple future scenarios for sub-Saharan Africa have been modelled to consider how various family planning-related investments might affect population growth. These have been built using data from the Track20 Project. The project monitors global progress in extending access to modern contraceptives to additional 120 million women in the world’s 69 poorest countries by 2020.

Let’s examine the data.

Wanted fertility: the black line represents sub-Saharan Africa’s population to 2100 based on estimates by the United Nations Population Division. The blue line represents its population to 2100 if every woman had only the number of children she wanted. Currently, women in the region have an average of 0.7 more children than they want. If that number went down to zero over the next five years, the population in 2100 could change by 30%.

Education: another link between empowerment and population growth is the transformative impact of secondary education for girls. Educated girls tend to work more, earn more, expand their horizons, marry and start having children later, have fewer children, and invest more in each child. Their children, in turn, tend to follow similar patterns, so the effect of graduating one girl sustains itself for generations. Though the impact of education is sweeping, our model looks at just one narrow aspect of it: a shift in the age at which women give birth to their first child.

The pink line represents sub-Saharan Africa’s population if every woman’s first birth were delayed by an average of approximately two years. The average age at first birth for women in Africa is significantly lower than in any other region. Currently, it is 20 or younger in half of African countries. This scenario doesn’t have anything to do with women having fewer children. It just has to do with when they start having them.

Consider this thought experiment. If every woman started having children at age 15, then in 60 years you’d have four generations (60/15=4). But if every woman started having children at age 20, then in 60 years you’d have three generations (60/20=3). Even if those women had the same number of children in each generation, the total population would be one-quarter smaller in the latter scenario. To be conservative, we assumed a less substantial delay in our model. Still, it changes the projected population by nearly 10%.

All well-meaning Africans will support sending girls to school and giving them access to information about family planning and contraceptives when they ask for them.

And I hope we will stop shying away from also pointing out that empowered women make millions of individual decisions that add up to a better demographic situation for themselves, for their children, and for Africa.

A version of this article was first published in the Goalkeepers Report

Alex Ezeh, Dornsife Professor of Global Health, Drexel University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.