A Rwandan hero who exploited superstition to save lives during the genocide has died at 106

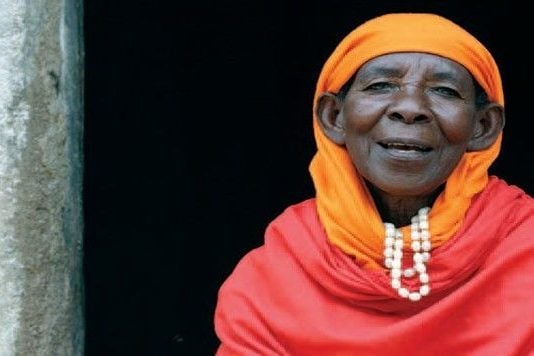

Sula (Zula) Karuhimbi, who died Dec. 17 at the impressive age of 106, lived her whole life in the village of Musamoin in central Rwanda, where she is celebrated as a hero.

Sula (Zula) Karuhimbi, who died Dec. 17 at the impressive age of 106, lived her whole life in the village of Musamoin in central Rwanda, where she is celebrated as a hero.

A Hutu widow born into a family of healers in the Gitarama district, she is remembered as one of the so-called indakemwa (righteous): Hutus who saved Tutsi lives during the 1994 genocide.

At the time, Karuhimbi, who declared she was born in 1912, which would have made her 82 (though older reports say she might have been 72, or even 69, and it’s nearly impossible to confirm for sure). According to reconstructions from the Université Catholique de Louvain (Belgium), the University of Texas, and the Kigali Genocide Memorial, she lived alone and would lodge workers to supplement her income as a healer and a sustenance farmer.

As the ethnic violence reached her district and the Interahamwe, the Hutu militia responsible of the genocide, began slaughtering Tutsi, Karuhimbi refused to join the massacre, and instead, according to her testimony, she hid dozens of people. “I put [the people] here in the compound and covered them with dry leaves of beans and baskets,” Karuhimbi said. “I hid so many people that I don’t know some of their names. I hid little babies I found on the backs of their dead mothers, and I brought them here.”

Karuhimbi remembered seeing ethnic violence dot her entire life, and said that just as her family and in-laws hid Tutsi during previous bouts of genocidal violence (presumably in the 1960s, when a first wave of violence against Tutsi erupted, forcing many to flee as refugees), she felt she was responsible to save as many people as she could.

She turned superstition in her favor. As a woman, a healer, and a widow, Karuhimbi was believed to be a witch possessed by the so-called Nyabingi, powerful evil spirits. She used the belief against the militia: When she was accused of hiding Tutsi in her hut or in her garden, she would suggest that the militia go take a look at the risk of being attacked by the evil spirit.

She recalls going to a bedroom and making noise with casserole dishes and stones, then shouting spell-like words at militia members, who became frightened enough to leave her alone. “I used to say ‘If I die, you will also die, but the [Nyabingi] will eat [you],” she remembered in a video.

Thanks to her manipulation of traditional beliefs—she even used poisonous herbs to cause irritation to the skin of militia members, making them believe it was sorcery—Karuhimbi saved as many as 100 Tutsis, many moderate Hutus and Twa (the third ethnic group of Rwanda), and even three white men in her home, feeding them from her plot of land and hiding them there.

She continued to live in the same hut she had before the genocide, even after Karuhimbi was recognized as a hero. She has been celebrated as an example of ubumuntu, a South African Zulu word used to express commitment against genocide: “I am because you are and you are because I am.”

Karuhimbi expresses the concept perfectly in her video statement. Far beyond the remembrance of her genocide, her words resonate poignantly in their succinctness. ”If you want to love,” she says, “you start with your neighbor.”