The “democracy of bread” is threatening to unravel Sudan’s three-decade dictatorship

The price of bread is, yet again, at the heart of protests in Sudan.

The price of bread is, yet again, at the heart of protests in Sudan.

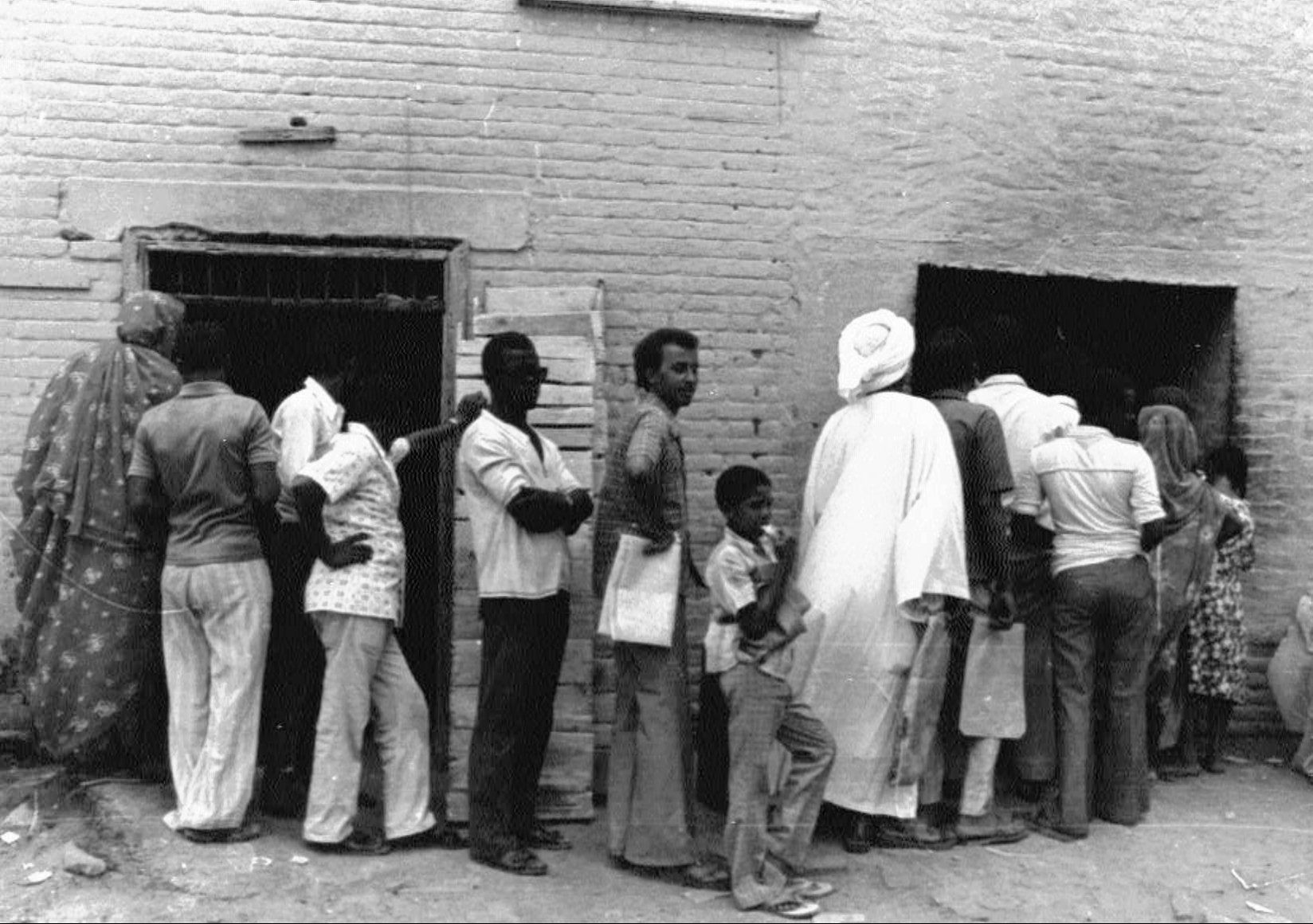

On Dec. 19, demonstrations began in the eastern city of Atbara after the government phased out wheat and fuel subsidies at the suggestion of international lenders. Before long, protests had turned deadly and spread to several towns and major cities including Omdurman and the capital Khartoum.

To quell the uprising, authorities disrupted internet connectivity, arrested opposition figures and critical journalists, and used tear gas to disperse growing crowds chanting, “The people want the fall of the regime.”

The wanton violence enveloping Sudan threatens the leadership of president Omar al-Bashir, who came to power after a coup in 1989. Yet the discontent over the tripling of bread prices illustrates the tenuous relationship between citizen and state, and how the latter scrambles to keep peace and power by offering handouts to the former. By underwriting wheat prices in exchange for political acquiescence, Sudan has for decades exercised what the Tunisian scholar Larbi Sadiki has called dimuqratiyyat alkhubz—or democracy of bread.

Scholars have traced the practice of bread for peace in North Africa and the Middle East to World War II when Allied forces started regulating food production and distribution processes in present-day Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon as a way to subdue social unrest. After independence, authorities nationalized flour mills and became heavily involved in food markets to deter pressure from below. During the Cold War era, governments like Sudan’s and Egypt’s also introduced subsidies grounded on the socialist economic model of centralized bread distribution in order to maintain order.

“Bread in Sudan, like Egypt, is referred to as aysh, Arabic for ‘life,’” says Isma’il Kushkush, a journalist who has extensively covered Sudan and East Africa. Successive governments, he added, have always been hesitant, even if partially, to lift those subsidies. But when they did, intifdada al- khubz—bread uprisings—have often erupted, leading to deadly riots. This was the case in Sudan in 1996, 2012, and even in early 2018, when officials cut subsidies on wheat imports.

Similar scenarios unfolded in neighboring Egypt in 1977, 2008, 2011, and most recently 2017, when officials reduced provisions of loaves from 4,000 to 500 per bakery. The 1988 “bread revolt” that shook the streets of Algeria also led to the death of as many as 500 people.

Efforts to liberalize Tunisia’s economy under the guidance of the International Monetary Fund in 1984 led to dozens of deaths forcing the government to cancel bread price hikes. To showcase that many families still live close to the breadline, Tunisians have marched while brandishing baguettes in recent years. And Libyans, faced with anarchy in a post-Gaddafi era, have complained about skyrocketing bread prices: where a dinar ($0.70) could fetch 40 loaves before 2011, it now affords them three small ones.

Inequality challenge

The current wave of anger about bread shortages is also a corollary of the shortcomings of economic growth, says Zachariah Mampilly, a professor of political science at Vassar College and the co-author of Africa Uprising. With a youthful population, fast-urbanizing cities, growing economies, and a huge gap between people and their rulers, many people continue to experience inequality and aren’t seeing the trickling down of wealth.

The protests in Sudan began in rural areas, he argues, partly because the regime “protest-proofed” the capital Khartoum, and thought the lack of population density outside major cities would make it difficult to organize mass protests. Yet these towns and villages, facing systematic marginalization for decades, are exactly where austerity measures dictated from the center are quickly felt.

Citizens, Mampilly adds, are saying, “Democracy should lead to a genuine transformation of our substantive concerns and that’s fairly not happened.”

For the 74-year-old Bashir, the protests come after the end of a two-decade-old US blockade, boosting hopes of reconnecting to the global economy and diversifying the oil exports-dependent economy. But Sudanese protesters have for two weeks now shown they need more than just bread, says Kushkush, and the enactment of stopgap palliative measures.

Given that the ruling party has said it would endorse Bashir’s candidacy in 2020, Mampilly says there’s “a very strong rejection of the narrative that suggests that all Bashir needs to do to stay in power is re-introduce bread subsidies. There’s a strong sense that would be a cynical move and unlikely to satisfy the demands of protestors at this point.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox