South Africa’s Human Rights celebrations ignore the man who fought for it

South Africa has learned to turn the most painful moments of its history into lessons for the present, yet the pomp and fanfare that now accompanies these days also threatens to whitewash history.

South Africa has learned to turn the most painful moments of its history into lessons for the present, yet the pomp and fanfare that now accompanies these days also threatens to whitewash history.

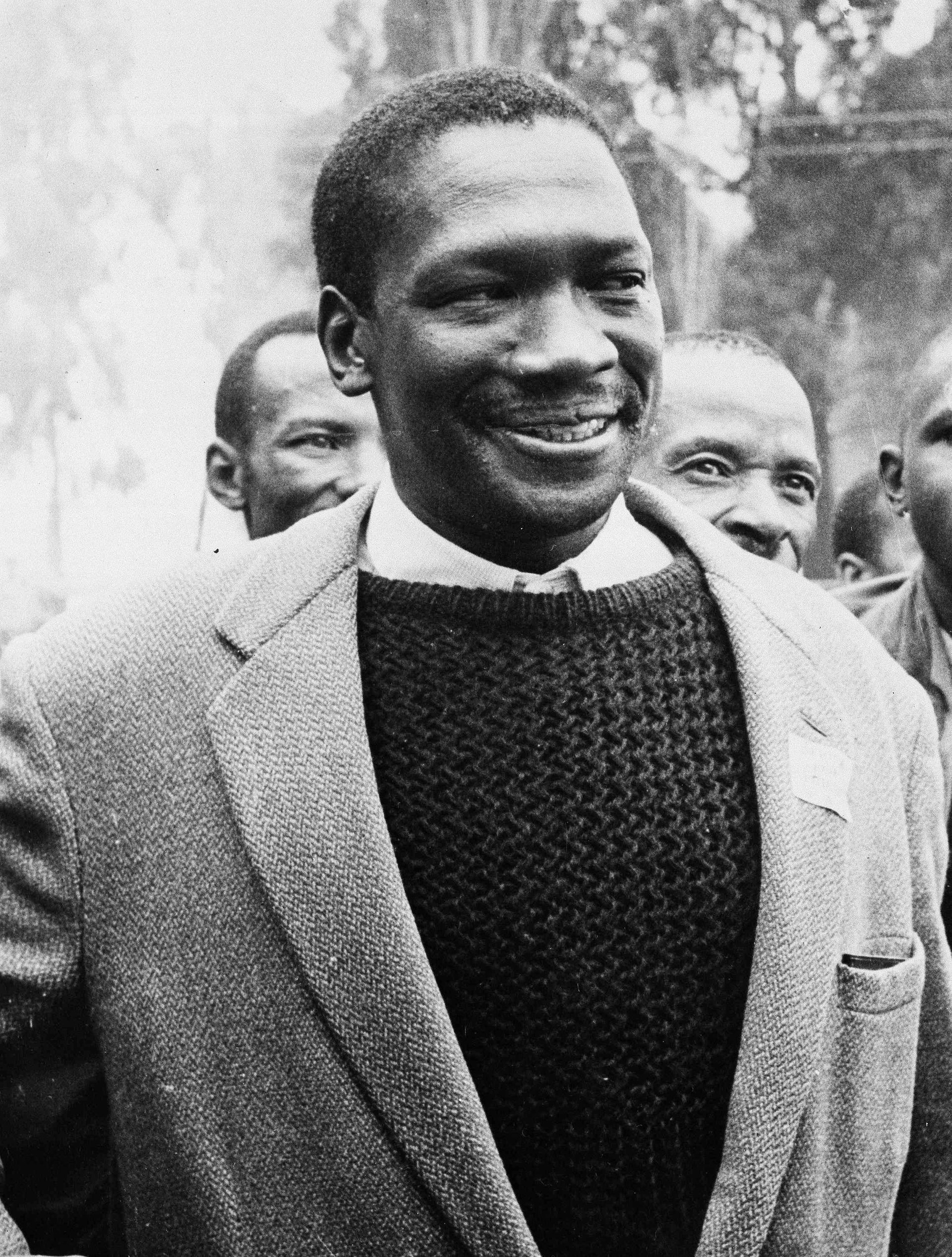

Now a public holiday, March 21 marks Human Rights Day in South Africa, commemorating the Sharpeville massacre of 1960, which became a catalyst in the fight against apartheid. Yet, just how the day is remembered today ignores the man who at the center of the campaign against apartheid, Robert Sobukwe.

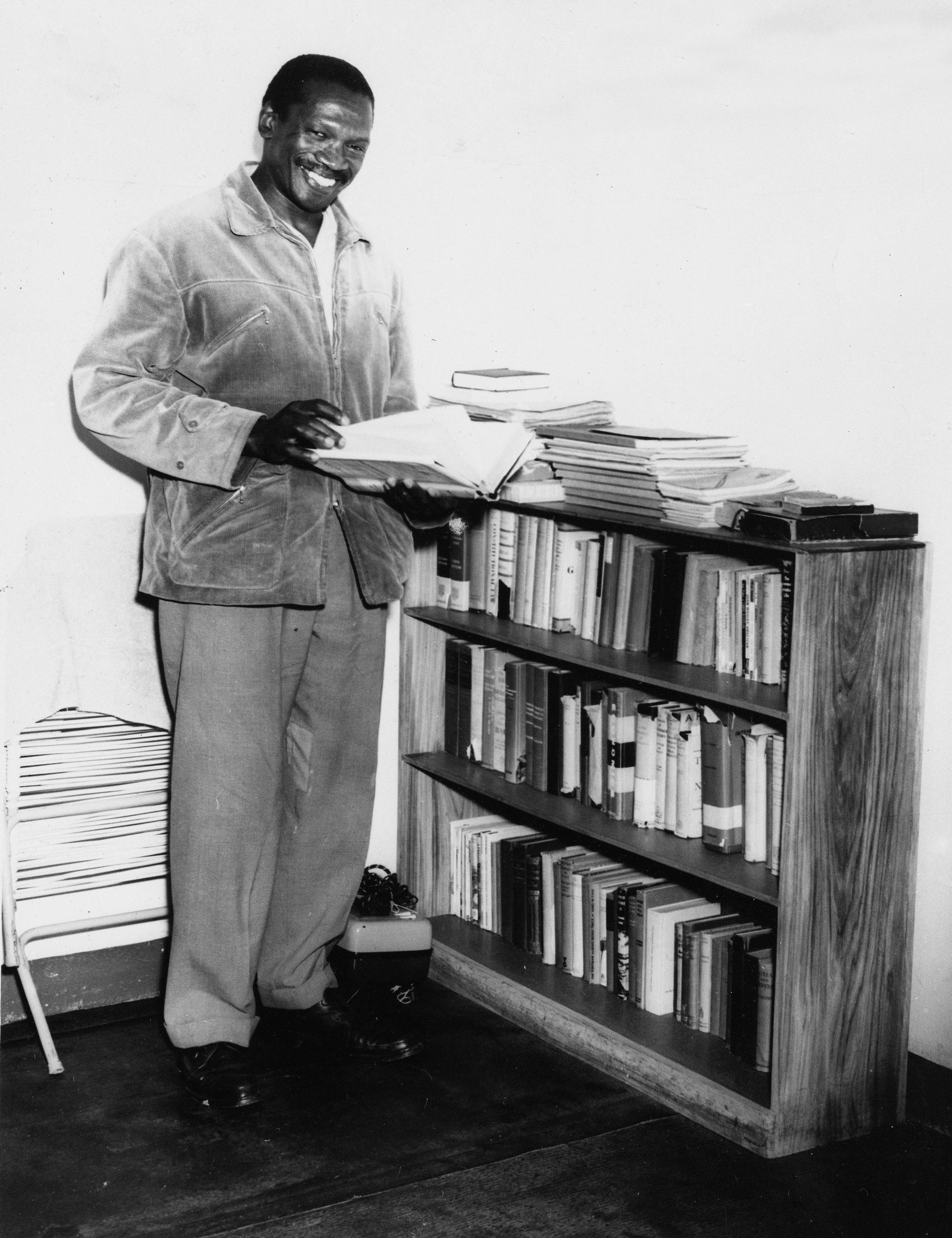

A contemporary of Nelson Mandela’s, Sobukwe had been a member of the ANC until 1958, when he and his followers deeply disagreed with the ANC over the Freedom Charter, the guiding document for the liberation movement. Where the ANC argued that South Africa belonged to all who live in it, Sobukwe and his followers called for a prioritization of Africans. Dubbed, the Africanists, Sobukwe and others broke away and formed the Pan Africanist Congress in 1959.

Their first campaign was meant to be the peaceful resistance against pass books, the identity document black South Africans were forced to carry. They planned that black people would leave their passes at home and present themselves at police stations to be arrested. Sobukwe’s reasoning was that if thousands of black workers were arrested, it would bring the economy to standstill, and force the apartheid government to reconsider its stance.

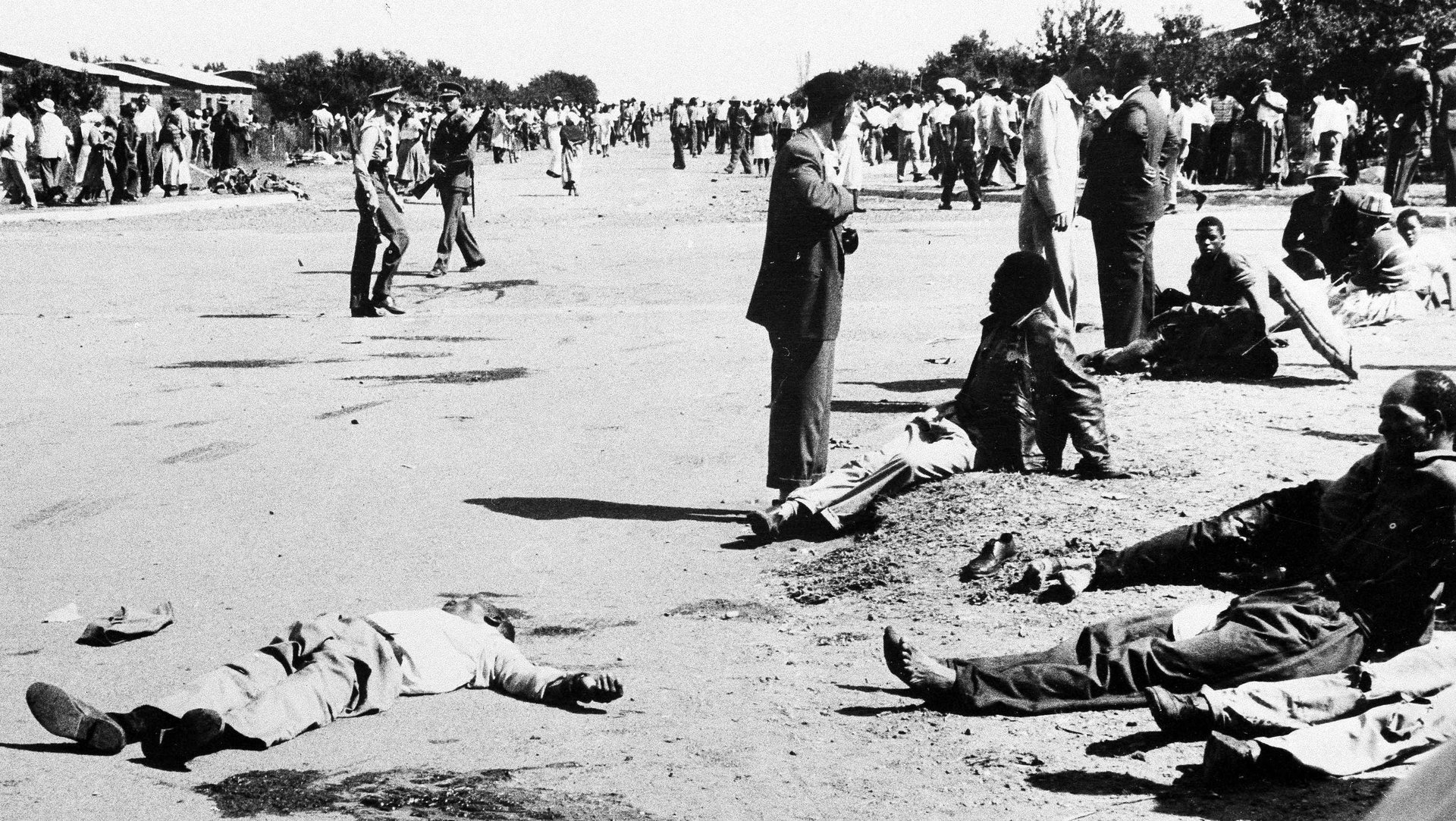

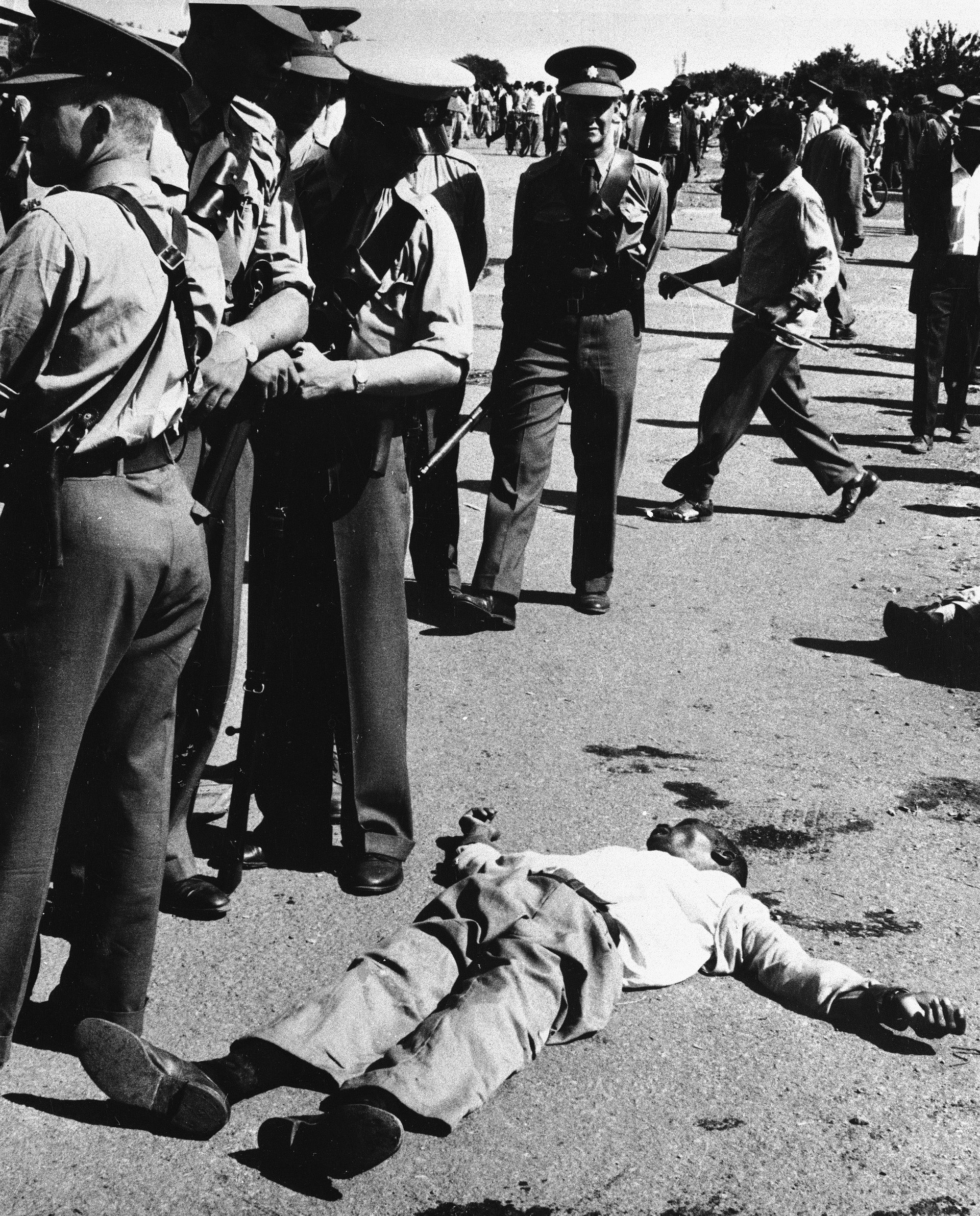

Sharpeville massacre

“No one outside the PAC was sure how seriously to take the PAC anti-pass campaign. The ANC leaders derided it. The white press largely ignored the PAC campaign,” journalist Patrick Duncan wrote. The ANC went as far as trying to discredit the campaign as “sensational” and without “prospect of success,” in an editorial for the Sunday Times newspaper on March 20, 1960.

On the morning of March 21, 1960, thousands went ahead with the campaign in the segregated townships of Sharpeville, in Vereeneging (a city south of Johannesburg), Orlando in Soweto and Langa in Cape Town. Reports of the protest in Sharpeville described it as “more festive than belligerent,” as an unarmed crowd of about 5,000 neared a group of 300 policemen. Then a small scuffle broke out and a policeman was accidentally pushed. He opened fire, and his colleagues followed suit, killing 69 people, wounding 180. When news of the deaths reached Langa, hundreds gathered in defiance of the apartheid governments ban on public meetings. Police killed three people and wounded 26 others.

The killings were beamed around the world and marked a shift in South Africa’s liberation movement and led to the United Nations recognizing apartheid as a human rights violation. Sobukwe was banished to a farm, then sentenced to jail for three years. Deemed a major threat, the apartheid government created the ‘Sobukwe Clause,’ which allowed for the specific and indefinite detention of Robert Sobukwe without trail. He was kept in isolation on Robben Island in a bid to reduce his influence. When he was released in 1969, he was banished to the Northern Cape and kept under house arrest until his death in 1978. Now, with his former party in power, Sobukwe’s role in freeing South Africa has been diminished.

“It’s all very much political,” said his son Dinilesizwe Sobukwe, speaking from the town of Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape, where his father was born and where a trust in his name has been established. “It has remained a sore spot for many, many years.”

Sobukwe’s son was five years old when the massacre took place. He has watched how many of the ideals that made his father a pariah, especially the right to land, have become part of the public discourse. At the same time, he has witnessed what seems like the systematic erasure of his father’s legacy. As recently as last month, deputy secretary secretary-general of the South African Communist Party, Solly Mapaila, tried to diminish Sobukwe’s incarceration on Robben Island.

In 2008, the family launched the Robert Manhaliso Sobukwe Trust to ensure to resurrect his legacy. They also established a learning center in the Eastern Cape town, which remains cleaved by segregation, and will open a museum there later this year. In 2017, the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg renamed a building for Sobukwe, who taught African Studies there in the 1950s at the university.

As South Africa’s political landscape leans in to the more radical, with the Fees Must Fall movement, the rise of Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters, and the call for the redistribution of land, Sobukwe’s profile is once again beginning to rise. Yet, one of his most important achievements on Mar. 21, 1960, continues to be downplayed. It doesn’t help that his former party has never quite recovered from its ban under apartheid, and is torn apart by infighting.

“That it has been changed to Human Rights Day, I don’t know why,” said the younger Sobukwe. The victims and families of the shootings in Sharpeville, and Langa, and the arrests in Orlando, feel marginalized by the generalization of this day, he adds.

“Even the people who lost their lives would want all to know that it happened.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation and untold African history in your inbox