How challenging the powerful global palm oil industry forced a Liberian lawyer into exile

The Upper Guinean Forest is considered one of the world’s most biologically diverse ecosystems, a dense tropical rainforest in West Africa stretching from Sierra Leone to Nigeria.

The Upper Guinean Forest is considered one of the world’s most biologically diverse ecosystems, a dense tropical rainforest in West Africa stretching from Sierra Leone to Nigeria.

Yet for years now, commercial logging and mining have impacted this “super” global eco-region, endangering hundreds of endemic plants and animal species. Deforestation has also become a critical issue for the forest cover, particularly with the growing demand for palm oil that is used in everything from cosmetics and food to cleaning products. This is especially true of Liberia, where palm oil firms have long eyed the forests given how much the country has succeeded in preserving large contiguous tree blocks.

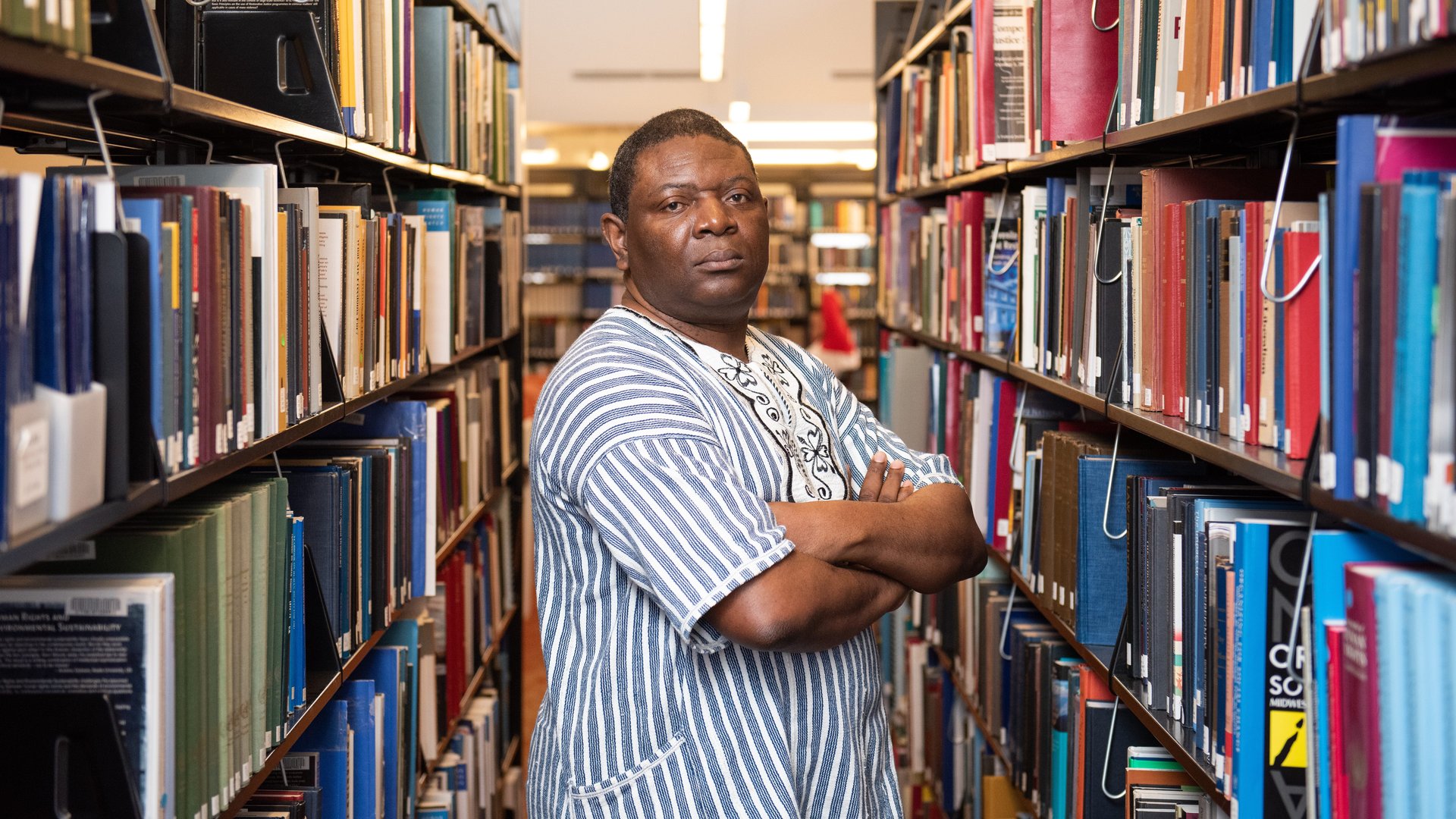

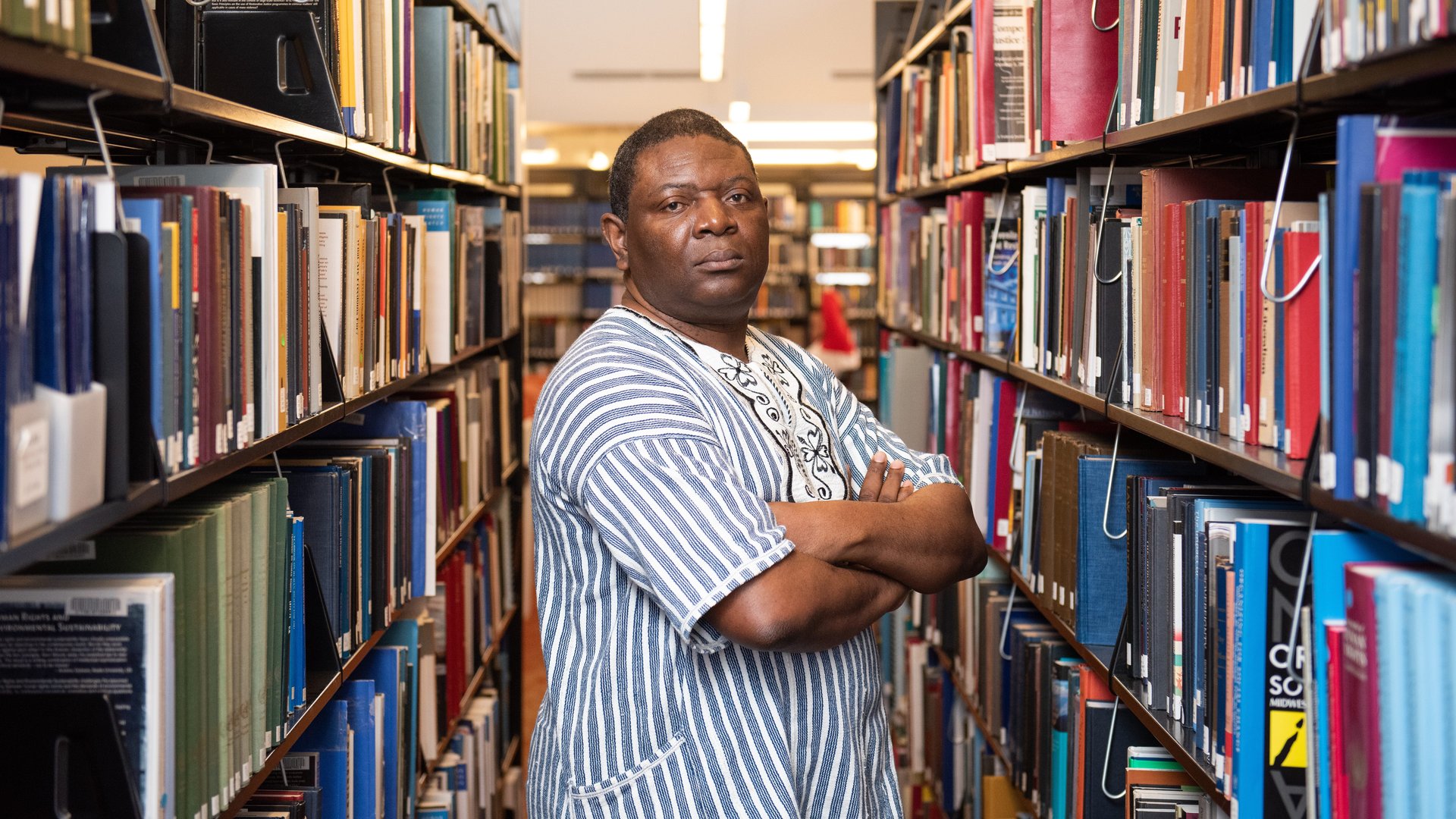

The efforts to ensure Liberia’s tropical forests remain intact is why Liberian lawyer Alfred Brownell, 53, was among those granted the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in San Francisco today. In this distinction, he joins Kenya’s Phyllis Omido who fought lead poisoning in her community besides South Africa’s Makoma Lekalakala and Liz McDaid who stopped a massive and corrupt secret nuclear deal with Russia.

After the end of Liberia’s civil war in 2003, the government sought to generate much-needed funds for growth through agricultural concessions and logging permits. Brownell had by then established Green Advocates, considered the country’s first non-governmental organization dedicated to environmental law. And looking at how the powerful palm oil companies were scrambling for rainforests, he sought to help conserve the nation’s majestic natural resource from the companies aiming to clear-cut it all for profit.

Globally, there have been growing concerns over the impact of palm oil too, with environmentalists warning cutting native trees to make way for palm trees threatens critically endangered species like the orangutan of Borneo.

In 2010, Liberia’s government signed a 65-year concession agreement to develop over 543,000 acres of land with Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL), a subsidiary of the Singapore-listed company Golden Agri-Resources. Yet the company was immediately accused of clearing community forests and desecrating burial grounds and sacred sites without notifying residents or adequately compensating them.

Because Brownell knew that GVL depended on its certification with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, he helped launch a community complaint that halted plantation expansion and protected 513,500 acres–or roughly 94% of the forest leased to GVL.

In 2015, campaign group Global Witness accused GVL of intimidating landowners and opponents of its operations to sign over thousands of acres of land during the Ebola crisis. Tensions rose after the company failed to deliver the promised jobs and roads to the community, leading to violent demonstrations against it at a plantation in Sinoe County. Brownell again intervened, securing the release of 14 out of 15 community members who were arbitrarily detained. One of them had died in mysterious circumstances.

With his rising profile, Brownell was targeted for his work and found himself at the center of a national manhunt—eventually escaping with his family in mid-December 2016 to the United States. There, he has continued his activism and teaches a course of human rights and global economy at Northeastern University’s school of law in Boston. In 2018, he also became the Beau Biden Chair’s inaugural recipient, a fund dedicated to preserving the lives and knowledge base of scholars who are in danger.

“I never hesitate—even though it’s extremely painful to talk about my story—to do it,” Brownell once said. “I’m confident in this cause with my very life and my very blood. There’s no way I’ll be silenced.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox