As measles spreads, should African countries issue health travel restrictions for Westerners?

The first headline of 2019 that really brought my attention to the anti-vax movement read: Measles returned to Costa Rica after five years by French family who had not had vaccinations. I thought the choice of words could have been stronger as the image it left me with was one of a homecoming event except what was being received was one of the world’s most contagious viral diseases that has no specific treatment.

The first headline of 2019 that really brought my attention to the anti-vax movement read: Measles returned to Costa Rica after five years by French family who had not had vaccinations. I thought the choice of words could have been stronger as the image it left me with was one of a homecoming event except what was being received was one of the world’s most contagious viral diseases that has no specific treatment.

Before the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963, major measles epidemics occurred almost every two to three years resulting in 2.6 million deaths a year. I continued reading the article about the French boy who brought measles to Costa Rica searching for the part of the article that would mention the new travel alert that had been issued by the country against French citizens or at the very least a mention of tighter travel restrictions for his country people. I am sure that would have been mentioned had this unvaccinated boy come from Guinea, Kenya or India. The headline would also have been something more menacing, perhaps: The African boy who started the Costa Rica measles epidemic.

In an almost apologetic tone, the article continued, “It is unclear why the five-year-old French tourist had never received a measles jab.” I was impressed by the presumption of innocence for a family that had intentionally chosen not to vaccinate their child against a highly contagious, dangerous disease. There were also no mentions of the travel bans I was so eagerly waiting to see as someone whose relatively weak passport makes me relish the few moments when someone else’s passport privilege is checked.

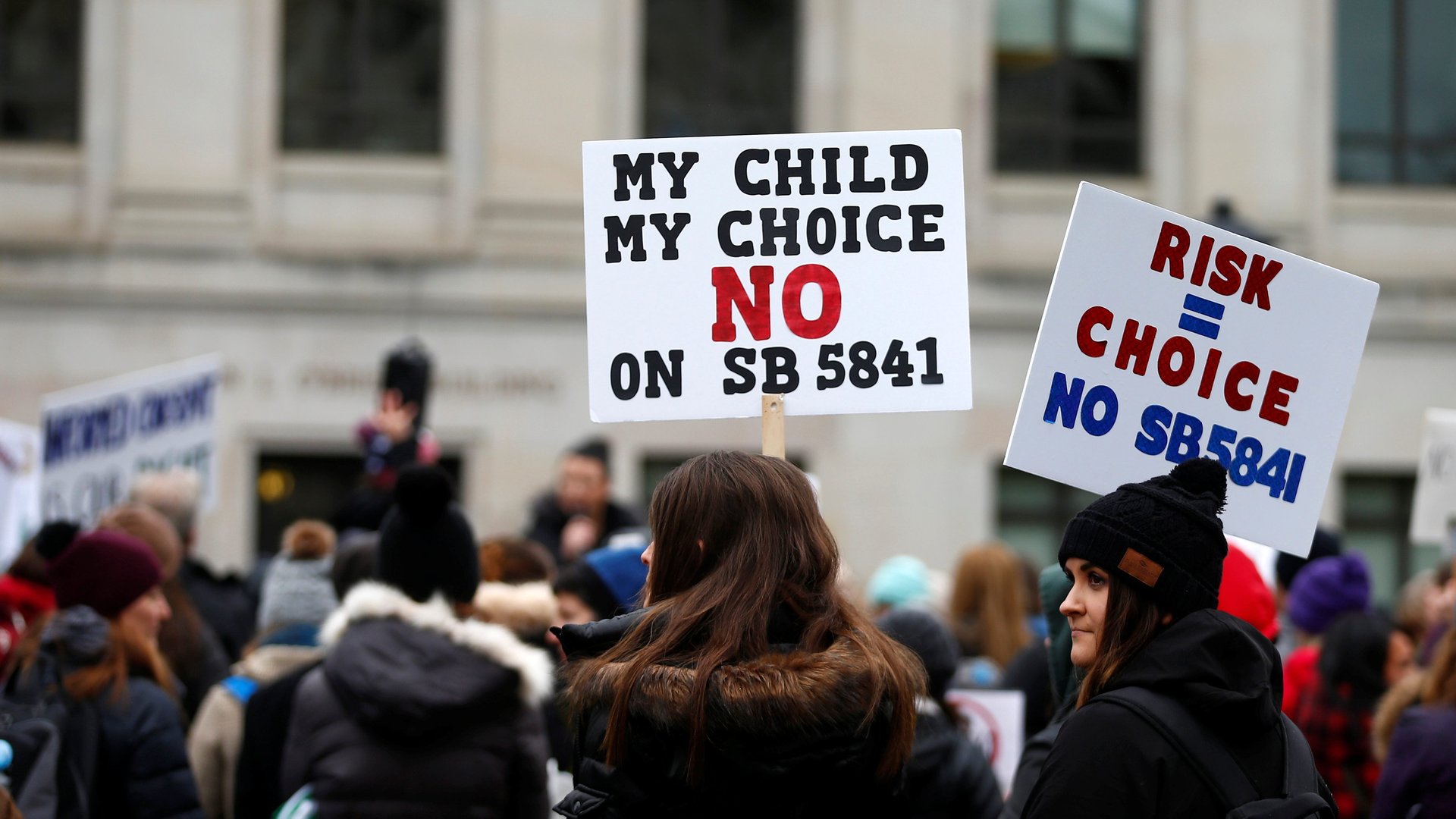

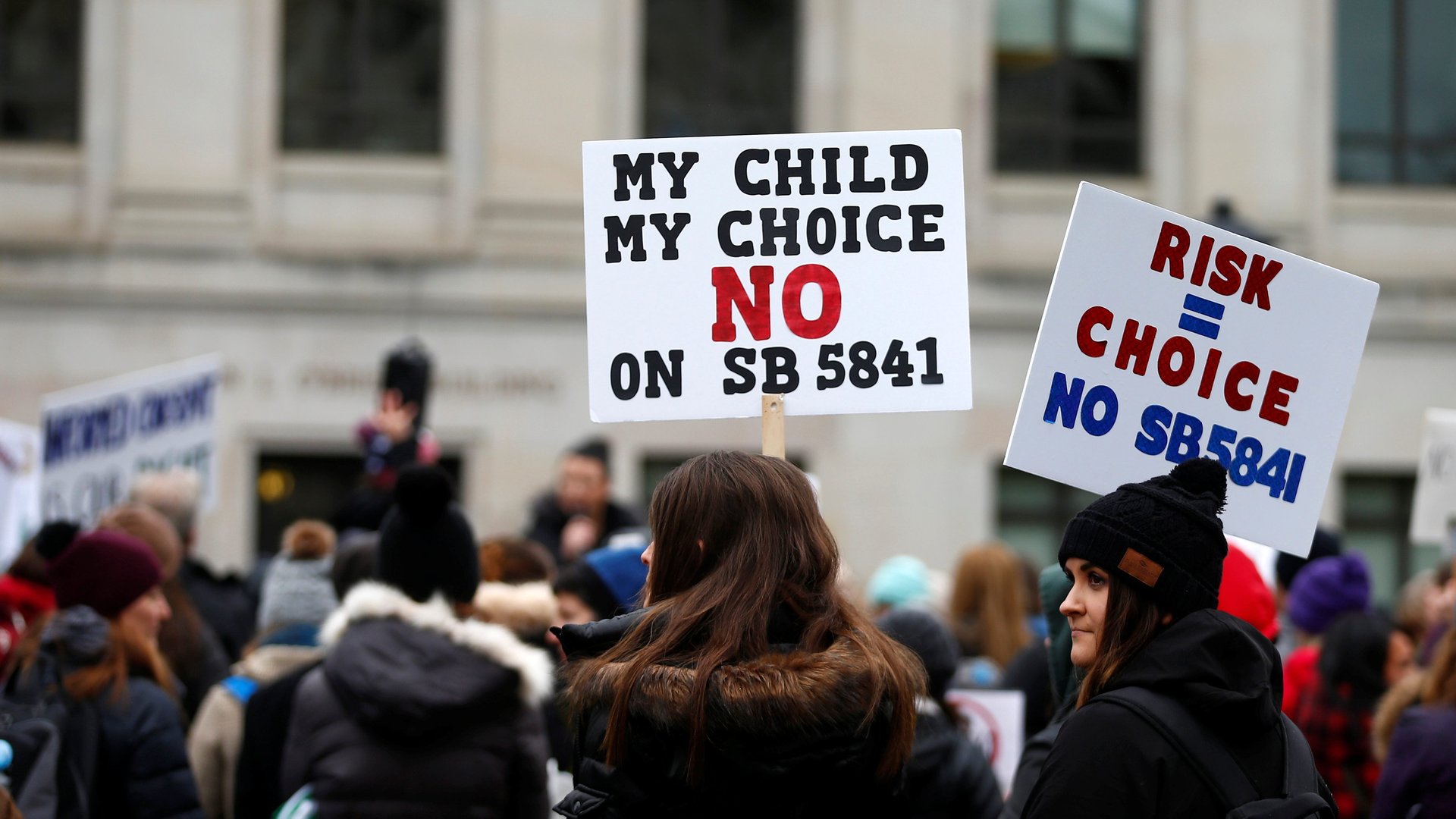

How big is the problem of this measles anti-vax movement? The anti-vax movement is the latest evidence of the disruptive power of fake news and disinformation in the digital age. It is spreading through content (articles, videos and posts) shared on social media platforms questioning the safety of vaccinations, false stories about children who have been adversely affected by vaccines, hoaxes about poisonous elements in vaccines etc.

This disinformation has convinced many people to not vaccinate their children. Recently, the US has reported over 700 measles cases in 22 states. More than 500 of those cases were in people who had not been vaccinated. This is the worst measles outbreak in the US in decades. In Europe, there have been 34,000 cases in the last two months.

Isn’t it time that our own African countries with high immunization rates—Ghana (95%), Senegal (90%) or Kenya (89%)—started issuing travel alerts against Americans and Europeans who could bring measles back into our borders? At the very least shouldn’t we be screening visitors from such places as Western countries did for people traveling from Africa (not only the three affected countries) during the 2014-2016 Ebola crisis or requiring proof of immunization. Is the European or American strain of measles less virulent than others? Nothing I have come across seems to reveal that.

Globally, measles deaths have decreased by 80% from an estimated from an estimated 545,000 in 2000 to 110,000 in 2017 mostly due to accelerated immunization activities. It is estimated 21.1 million deaths have been avoided from 2000 to 2017 because of the measles vaccine.

Measles is airborne, has no treatment and its highest mortality rate is in children under the age of five. Those who live can suffer lifelong complications such as deafness and brain damage. Measles can be transmitted by an infected person even up to four days prior to the onset of the telltale rash.

The Ebola movement

Now, let’s talk about another movement, you could call the “Ebola Deniers Movement.” They might not yet have been accorded the status of being a “movement”—deliberate, well-thought out, intentional—but that might be because of where they are based. Reading recent articles on how a quarter of the people surveyed in Eastern Congo do not believe Ebola is real, we are left with the feeling that they are somehow ignorant, reckless, perhaps superstitious.

When we really think about it, isn’t that exactly what Western anti vaxers are, except with the veneer of somehow being almost harmless and not ill-intentioned. It seems strange to compare measles to Ebola as in the reader’s mind—Ebola sounds much more terrifying.

The worst Ebola crisis was the 2014–2016 West Africa crisis that led to over 11,300 deaths in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. Contrast this to the 110,000 deaths every year from measles. Not to understate the devastation that Ebola caused in the affected countries. In addition to the deaths, the West Africa Ebola outbreak resulted in GDP losses of over $2.2 billion in the three countries in 2015, Liberia lost 8% of its doctors, nurses, and midwives to Ebola while Sierra Leone lost 7% of its healthcare workers.

Despite this, it is not an exaggeration to say that right now you are more likely to get infected and die from measles in the US or Europe (if you are unvaccinated) than you are to get infected by Ebola in DRC.

Where are the travel bans and the frantic headlines? Is it too much to ask that our African Governments start really scrutinizing visitors coming in from these “disease-ridden” areas?

This is not a matter of tit-for-tat, if a communicable disease like measles was to take hold in Africa, particularly most countries in Sub Saharan Africa, it would have a much more devastating effect than anywhere in the West given Africa’s low levels of healthcare infrastructure and healthcare workers per capita. We know if the tables were turned, there would not be a laissez-faire attitude towards letting Africans into Western countries.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox