The top South African CEO gig that no one wants

Eskom, South Africa’s power utility firm, has had 10 chief executives over the last decade—and there’s about to be another.

Eskom, South Africa’s power utility firm, has had 10 chief executives over the last decade—and there’s about to be another.

Current CEO Phakamani Hadebe has announced his decision to step down next month citing the job’s “unimaginable demands” which have had “a negative impact” on his health. Hadebe’s resignation from the post after only one year mirrors the short life-cycle that’s now associated with running one of South Africa’s most important organizations.

Since 2007, no Eskom CEO or acting CEO has stayed in the job longer than three years and since 2013, no CEO has stayed in the job longer than a year. Of the crop that have served in the role since 2007, eight chief executives have either resigned, citing personal reasons, or have been suspended over corruption allegations. Before Hadebe, the company’s last full-time CEO Brian Molefe resigned in 2016, only a year after being hired, after being being implicated in a government corruption report. Matshela Koko, who was acting CEO between 2016 and 2017 until his suspension, has described the role a “poisoned chalice.”

But the position of CEO has not always come with a short shelf life though: in the years between 1994 and 2007, Eskom had only two CEOs.

Power problems

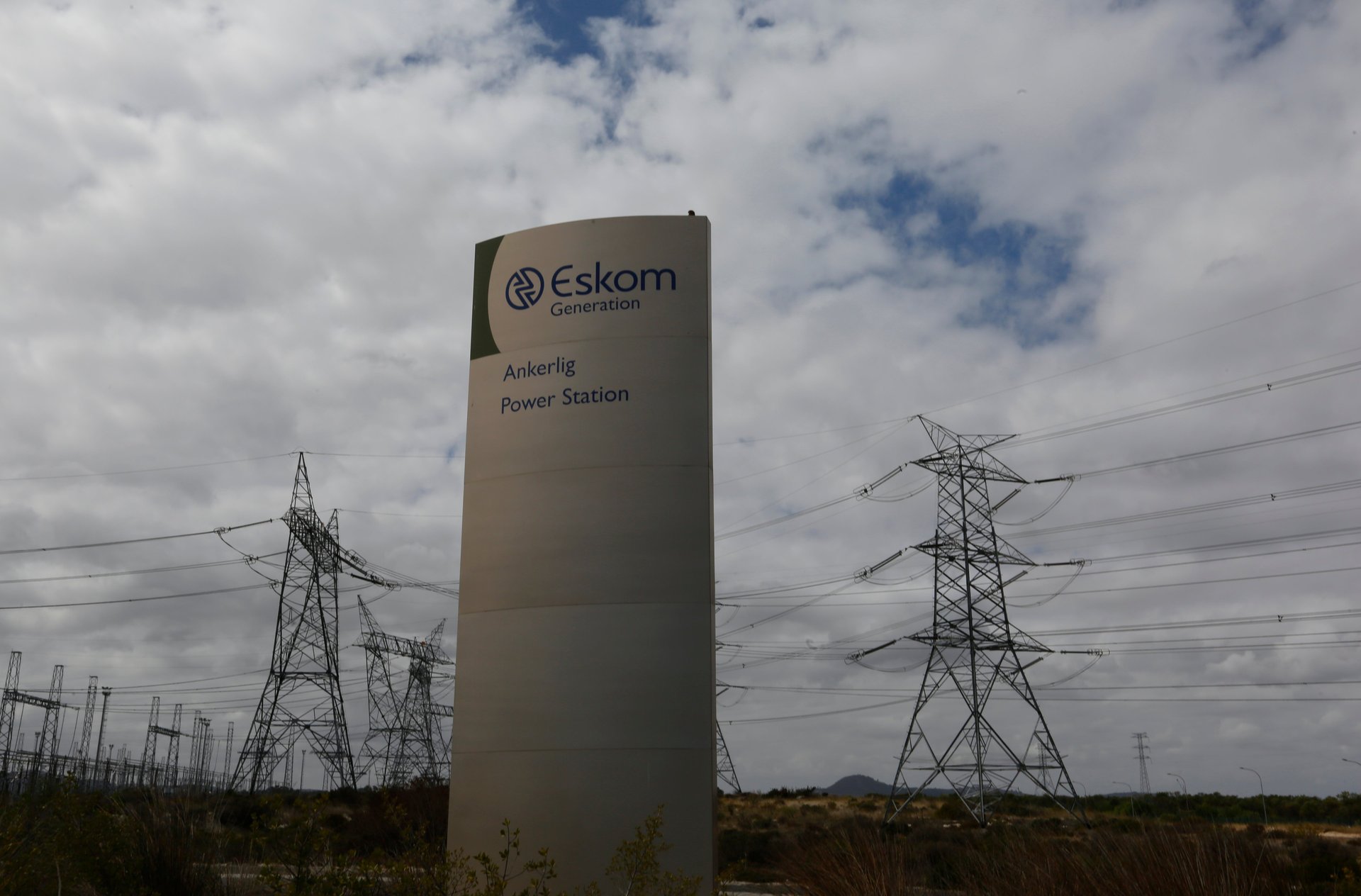

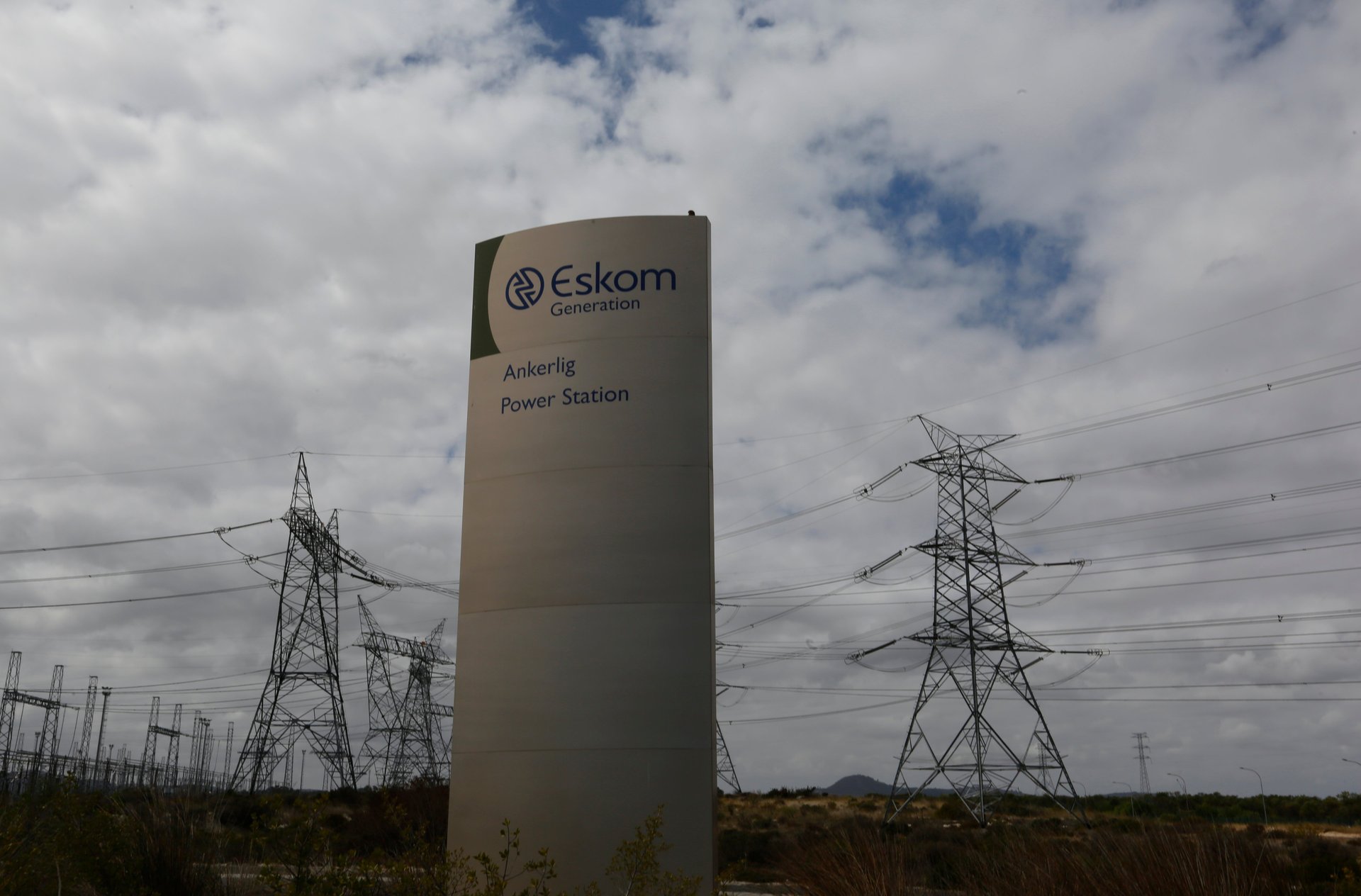

When outgoing CEO Hadebe talks about Eskom’s “unimaginable demands,” it’s not difficult to figure out what he might mean. Eskom currently generates 95% of electricity used in the country and as such, the pressure that comes with running such a key social and public entity is significant.

But Eskom also has a workforce problem: while it is South Africa’s largest employer, it is overstaffed by up to 66%, according to World Bank research (pdf, page 50). Eskom plans to reduce its staff size (pdf, page 35), but against the backdrop of rising unemployment in South Africa, that’s bound to be a slippery slope that will require strong political will.

Then there’s the growing mountain of debt which now stands at nearly $35 billion. Financial results last November also showed that 90% of Eskom’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) goes to interest payments on debt not leaving much room for investment in power infrastructure.

And the results of that shortfall are clear as Eskom’s woes have translated into real-life, everyday difficulties for South Africans as electricity blackouts—or “loadshedding,” as Eskom calls it—have become increasingly normal in Africa’s most advanced economy. Some of Eskom’s supply troubles are rooted in being unable to expand infrastructure quick enough to cope with population growth and, by extension, demand, especially since the end of apartheid in 1994 as previously unconnected municipalities got plugged into the national grid.

Regardless of whoever the next CEO of Eskom is, president Cyril Ramaphosa will also likely share some of the burden of the utility’s failings, should they continue. But while analysts think the company is on the precipice (Goldman Sachs describes Eskom as the biggest threat to South Africa’s economy), Ramaphosa is maintaining a hopeful outlook, telling investors recently that “Eskom is too big to fail.”

For his part, Ramaphosa is banking on more than rhetoric to save Eskom: in addition to a $4.7 billion government bailout over the next three years, Ramaphosa has also committed to breaking up the utility into more efficient units as part of an ambitious—but already criticized—revival plan.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox