Luxury safaris are trying to reinvent by getting greener and curbing an “Out of Africa” culture

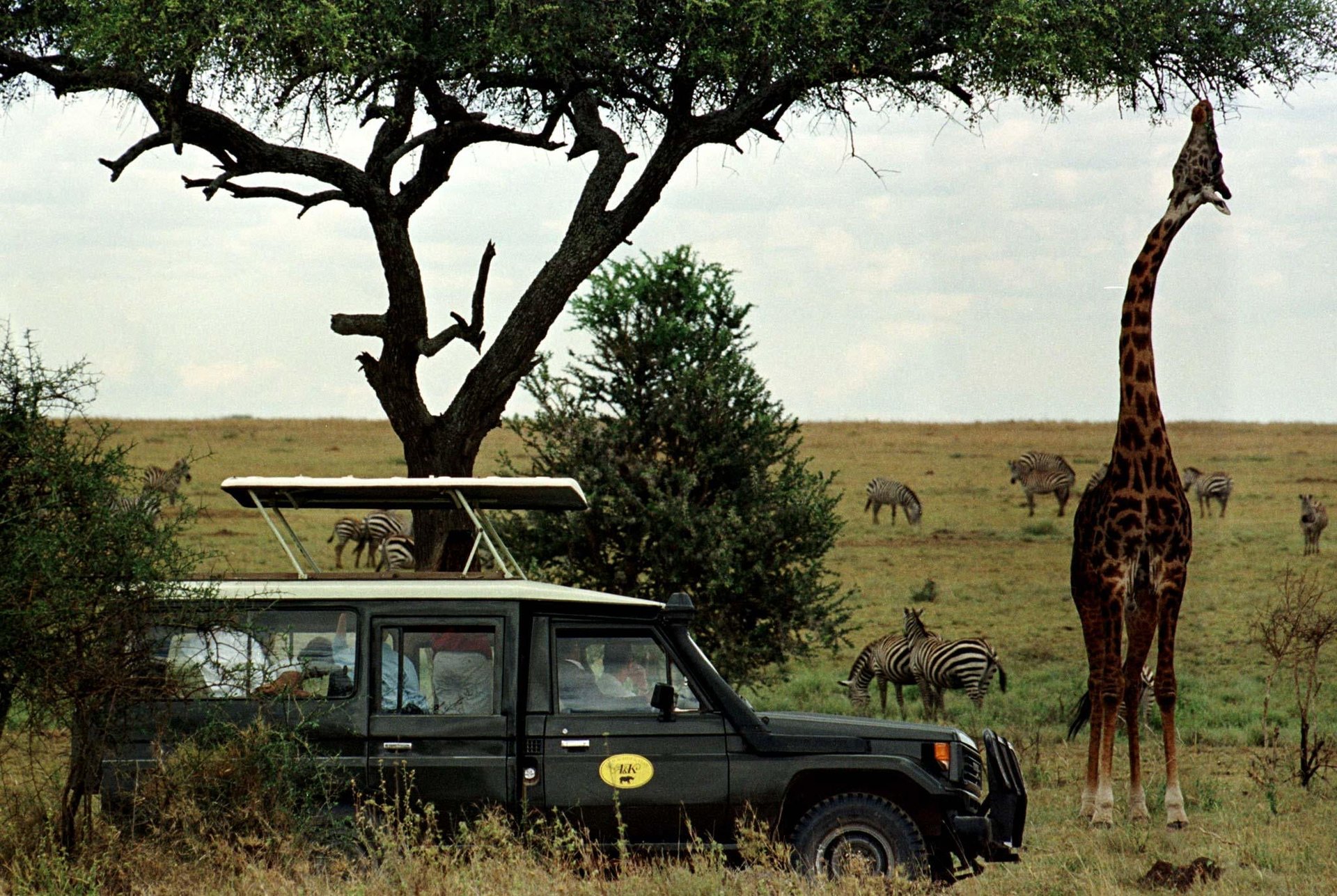

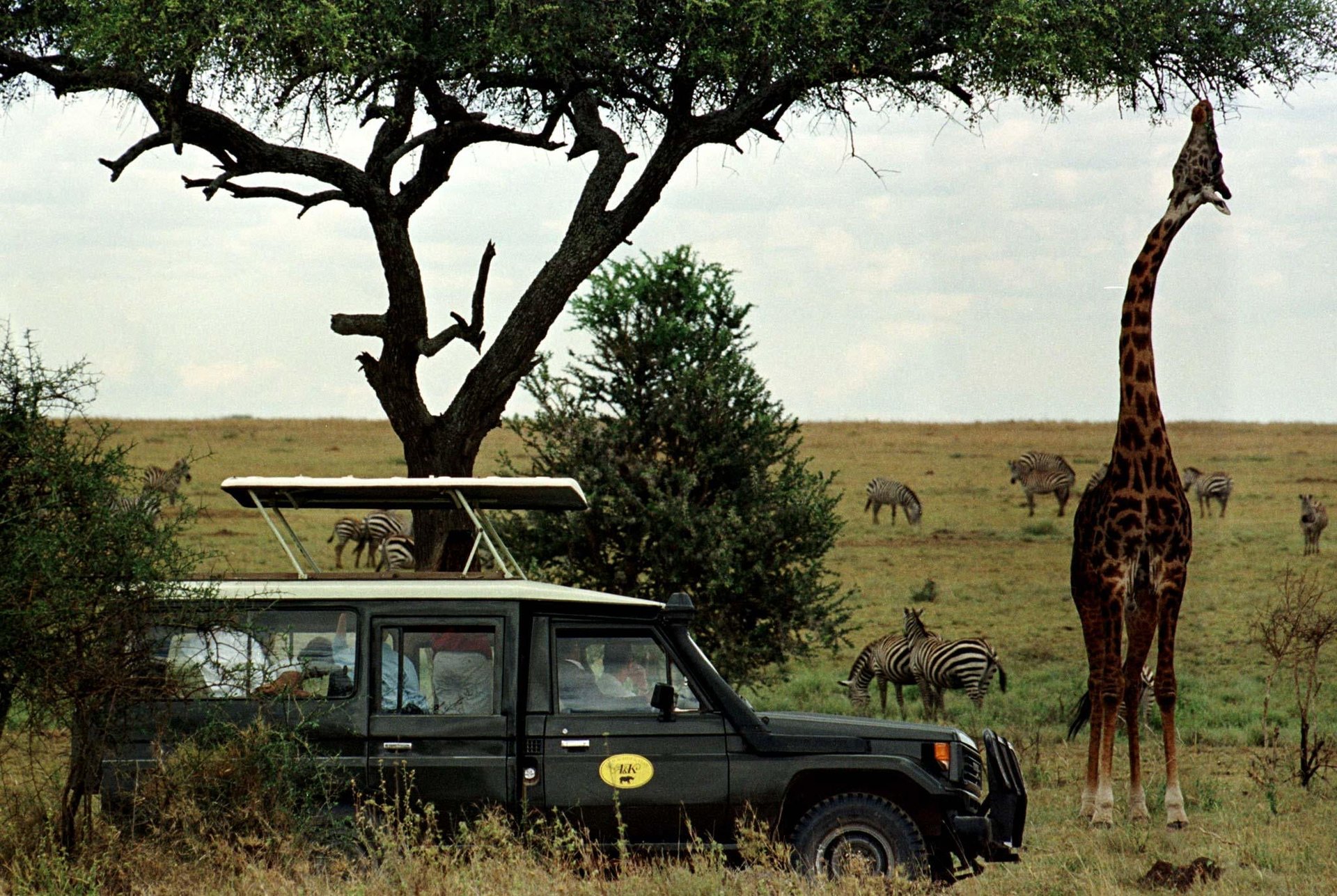

Evolving from elite colonial sport into bucket-list favorite, safaris have long played to western fantasies of the African wild. Given prices that start at about $750 per person per day (easily increasing by three or even ten times that), this “trip of a lifetime” naturally comes with big expectations.

Evolving from elite colonial sport into bucket-list favorite, safaris have long played to western fantasies of the African wild. Given prices that start at about $750 per person per day (easily increasing by three or even ten times that), this “trip of a lifetime” naturally comes with big expectations.

And because the qualities you’re actually paying for are difficult to capture (exclusivity, colorful local guides, location), lodges put a lot of energy into crafting dreamy settings, from Instagrammable bathrooms to plunge pools overlooking honeyed landscapes to four-poster beds surrounded by trappings of colonial grandeur.

However, the world is changing and as millennial tastes and influences start to have an impact long-held consumer habits globally, the idea of the old school, pith helmet-wearing colonial safari ride isn’t as appealing as it might once have been.

“The industry is in need of a complete rebrand, ” says Fred Swaniker, the much celebrated Ghanaian entrepreneur and founder of the African Leadership University. Swaniker was speaking at the African luxury tourism industry’s annual We Are Africa conference last month where the great and good of the sector gathered.

The changes have been coming—incrementally. For example, the rising popularity of using electric game drive vehicles. The very first e-game drive vehicle was introduced on the continent in 2010, when South African lithium battery manufacturer Freedom Won converted a conventional Jeep Grand Cherokee to run off electric battery power.

Anyone who has clocked a few hours driving through the bush knows how overbearing the sound (and smell) of a diesel motor can be—and the calm that descends the moment that engine is silenced.

Electric vehicles are the most visible part of an important larger trend in the industry that is making green building, water and waste recycling, and off-grid energy solutions a norm that clients should come to expect as part of a luxury experience. That said, for real sustainability, the safari industry may need to look beyond “technological fixes” to something less tangible.

While the Out of Africa romance has long beguiled the western imagination, international millennial tastes are challenging that narrative, as are those of Africa’s own affluent urbanites. In other words, even as more luxury lodges ditch colonial references and let local, eco-friendly solutions guide their aesthetic, a truly visionary industry would speak more directly to the market in Africa.

“The safari experience is not appealing to middle class urban Africans,” says Swaniker, explaining that the political power of Africa’s own rising middle and upper classes is what will make or break conservation – and by extension, the safari industry – in the long run. “If nature is not relevant to urban Africans and the rising middle class, then it’s going to be lost forever.”

EV Safari

Reading about Freedom Won’s prototype in an airline magazine, the manager of Chobe Game Lodge, Johan Bruwer, immediately saw the beauty and logic of a silent, eco-friendly wildlife viewing option. The only permanent lodge within Botswana’s famous Chobe National Park Chobe Game Lodge went on to work with Freedom Won to develop Botswana’s first and the continent’s largest fleet of e-vehicles (five of nine game drive vehicles, and all five of its boats for wildlife cruises on the Chobe River).

While it seems the obvious route to go, nine years since e-vehicles first appeared, surprisingly few lodges have gotten onboard. Cost is a supposedly a factor. Freedom Won’s conversions start at about $36,000, a price tag that co-founder Antony English acknowledges does not at current volume turn a profit, but which he accepts as the vehicles remain “a side-line, but a passion”. Additionally, if using solar power to charge the vehicles, a solar installation must be invested in if not already in place (English says solar installation costs for the cars add approximately 50% of the car’s cost to the final bill). However, the capital outlay is recouped over time in e-vehicles’ lower operating and maintenance costs, plus massive savings in fuel.

In the end, the few pioneering lodges that have gone electric in any meaningful way have been motivated by considerations beyond cost-benefit ratios. They have also put skin in the game.

Driving between his properties in Zambia back in 2010, Green Safaris’ founder Vincent Kouwenhoven’s eureka moment came when switching off his Land Rover to watch a pack of lions. A frequent traveller to Silicon Valley where Toyota’s Prius and Teslas had become ubiquitous, Kouwenhoven suddenly imagined what it would be like to hear the sounds of the bush throughout one’s entire game drive.

Developing Zambia’s first “e-Landy” prototype, he quickly realized he was more interested in disseminating the concept than launching another company, and made his design open source. Having since commissioned Freedom Won to convert all of Green Safaris’ vehicles (game drive vehicles, boats, and quad bikes), Kouwenhoven calls the silent safari “a true differentiator for exploring the bush.”

Cheetah Plains Lodge owner Japie van Niekerk would agree. The only lodge on the continent that can boast a “full fleet” of e-vehicles, the newly launched luxury property in South Africa’s Sabi Sands is attempting to set itself apart in various ways, and its fleet of five “state of the art” e-game drive vehicles offers an undeniable distinction.

“No one had a vehicle on the market that suited our needs, so [I thought] we may as well do our own thing and know exactly how it works,” says van Niekerk, an avid motor sport competitor whose main concerns were around reliability (imagine inadequate torque in the face of a stampeding elephant herd) and comfort. Speaking to the latter, his model (a Toyota Land Cruiser fitted with Tesla batteries) comes with amenities like reclining, heated seats, and USB plugs, as well as a price tag of $100,000 – a cost van Niekerk dismisses. “[It’s] the most important tool in my business. Your customer sits four to six hours a day on that vehicle. People spend millions on interior decorating, but then want to employ economics when it comes to vehicles,” he says.

While these three operators are unique on the continent in terms of having converted most if not all of their vehicles, the constantly improving prices and technology for lithium batteries cause insiders to anticipate that silent safaris will become the new luxury standard in the next five years.

Companies like Electric Safari Vehicles, the newest player in this space, are banking on it. CEO Steve Blatherwick says the company, which also installs Tesla batteries in its conversions (about $60,000 a pop), has plans to complete 40 conversions by the end of this year from Kenya to South Africa, and as many as 150 in 2020.

In a world where true wilderness and stretches of unwired time are ever more scarce, they are already among the ultimate luxuries. The industry would do well to maximize that asset. As Kouwenhoven notes, “at the end of the day, it’s about being close to nature.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox