A recently discovered trove of photos shows life in Uganda during Idi Amin’s troubled reign

In 2015, researchers working in the storeroom at the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation forced open the lock on an unremarkable filing cabinet.

In 2015, researchers working in the storeroom at the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation forced open the lock on an unremarkable filing cabinet.

Inside were thousands of small wax envelopes, neatly arranged in rows, each containing a number of medium-format photographic negatives. In all there were 70,000 images. The vast majority of them date to the 1970s and the presidency of Idi Amin.

Amin is one of the 20th century’s most notorious dictators. In a recent PBS television series, he features alongside Kim Il Sung, Mussolini and other “Profiles in Tyranny.” In Uganda, the memory of the Amin years has been suppressed by a government keen to promote political amnesia. There are no memorials to the dead; neither are there monuments or other institutions that encourage deliberation over the Amin years.

These photographs offer one of the first opportunities for public reflection, and a small selection of them—about 150 images—are now on display at the Uganda Museum in Kampala. The exhibition, which we helped curate, is titled “The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin” and will be open until the end of 2019. For Ugandans and other visitors it is a place where a traumatic and divisive history can be assessed.

Amin’s aggressive populism

Idi Amin came to power in 1971 after overthrowing the government of Milton Obote, the president who had presided over Uganda’s independence from British colonial rule.

Obote had relied on state-run media to amplify his political power, and Amin inherited a powerful network of radio stations. The extensive reach of official media encouraged Amin and his officials to think of themselves as spokesmen for Ugandan commoners. Issues that had formerly been decided behind closed doors were discussed openly; matters that had once been determined by experts were made subject to the popular will. For some people it was hugely empowering. For others – especially for civil servants and other professionals – the Amin government’s aggressive populism was a mortal threat.

As far as we know, very few of the photos they took were ever printed or published. The film was developed, and then the negatives were placed in envelopes, labeled and placed in a cabinet.

This had been, until now, an unseen archive.

Making a show of criminality

So why were these photos taken?

It seems that they served, primarily, as documentation.

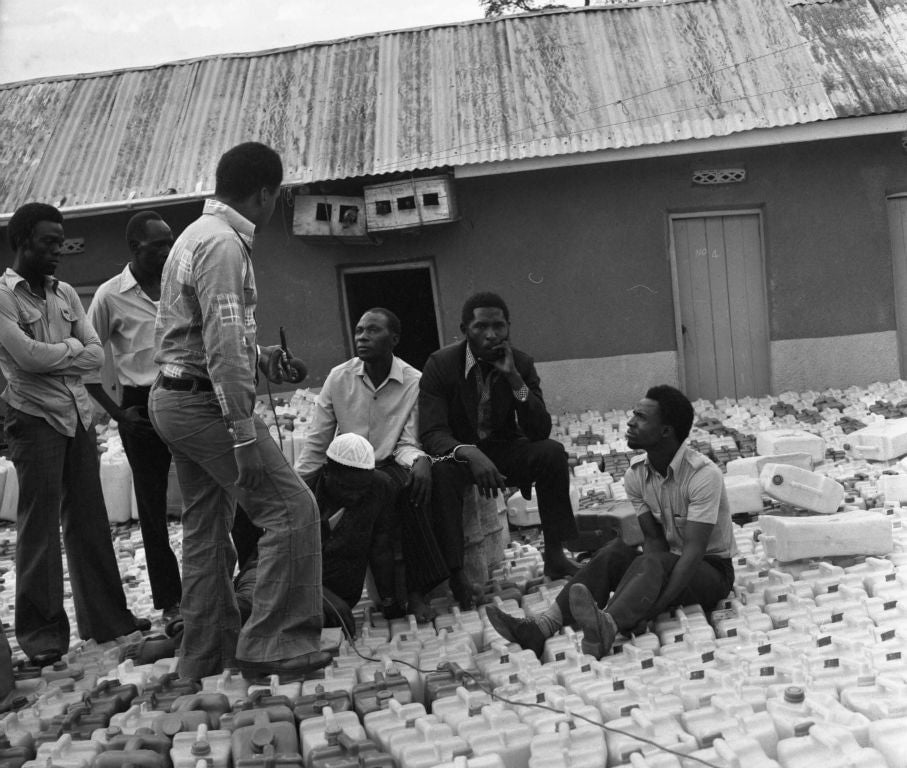

Amin’s administration governed Uganda with the fervor and energy of a military campaign. It targeted otherwise obscure social issues – smuggling, overcharging consumers, the dominance of Asian business interests in the economy, the cleanliness of city streets – and transformed them into urgent political problems that demanded action.

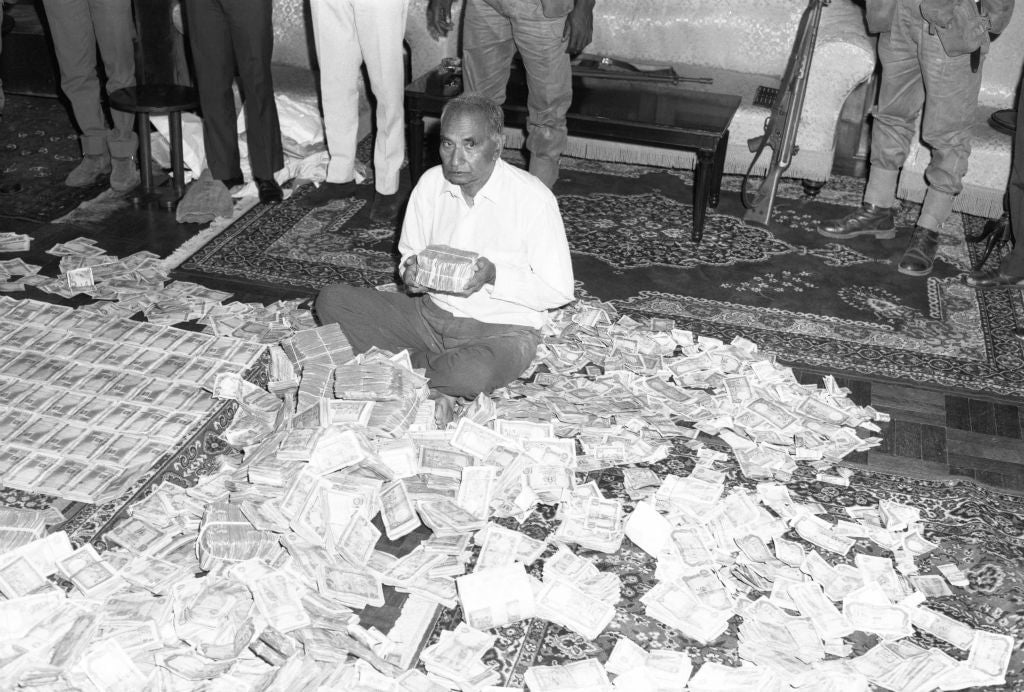

For example, in 1972, tens of thousands of South Asians were obliged, by presidential decree, to leave Uganda. The Amin government labeled them as usurpers of black Ugandans’ economic power, a foreign minority whose usurious self-interest ran against the majority.

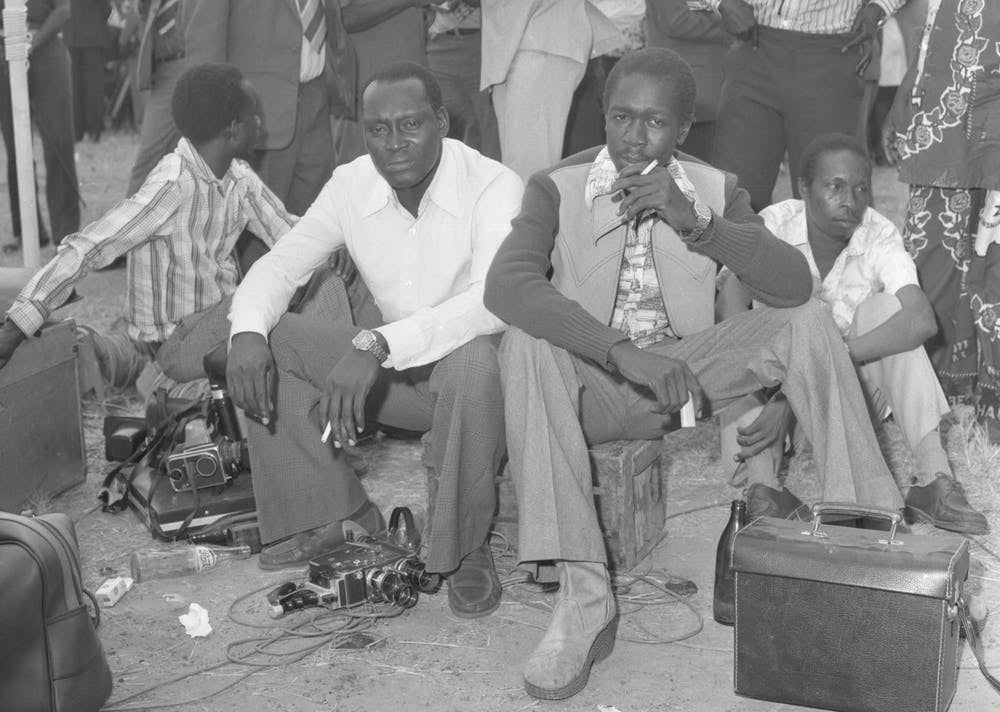

The cameras made the evils of usury, stealing and smuggling visible. People accused of criminal acts were paraded before the cameras, with crowds often gathered to witness the occasion. There, the evidence was laid out for all to see. Here are jerry cans full of smuggled paraffin, arranged in long rows; there are neat piles of hoarded cash, signifying the evil of South Asians’ dominance of the economy; there are bottles of gin, stacked up around an accused smuggler.

The camera brought the judgment of the Ugandan commonwealth to bear in specific times and in specific places. In the presence of photographers, campaigners could show themselves to be acting in the interest of the majority. In the presence of a camera, the struggles and exertions of the decade could be seen as historically consequential.

The Amin government’s photographers were part of a media ensemble that helped craft a narrative of meaning, direction and national purpose to the age. That’s why so many Ugandans found reason to support the Amin government. The presence of cameras at public events transformed mundane and forgettable occasions into moments in a chronicle of national struggle. Many people felt as if they were acting in the light of history.

What the cameras didn’t capture

While there’s a richness to the documentary nature of the photographs, there are very few that capture the harsh realities of daily life in Uganda in the 1970s, such as unaccountable violence, a collapsing infrastructure and shortages of the most basic commodities.

As many as 300,000 people died at the hands of men serving Amin’s government. This violence – the torture and murder of dissidents, criminals and others who fell afoul of the state – largely took place out of public view, and there’s no trace of it the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation archive.

In 1979, the Amin regime was overthrown by a force of Ugandan exiles and Tanzanian troops. Since then, there have been scant opportunities for Ugandans to learn about Amin’s presidency. After a decades-long exile in Saudi Arabia, Amin died in 2003. His remains are still buried there, awaiting repatriation to Uganda.

Debate around his legacy is only now finding a place in Uganda’s public life. So the thousands of recently discovered negatives – which were digitized as part of a preservation project organized by the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation, the University of Michigan and the University of Western Australia – are significant historical documents.

But when designing the Uganda Museum exhibition, we agonized over the absence of images that reveal suffering and death as facts of life in the 1970s. So we made an effort to present the photos in a way that acknowledges their status as instruments of Amin’s political self-interest.

In one part of the exhibition, we juxtaposed photos of the momentous events of public life with portraits of deceased people. In another part of the show, we highlighted particular episodes—the expulsion of the Asian community, the Economic Crimes Tribunal, the crackdown on smuggling—during which innocent people became victims of the regime. At the end of the exhibition, we put on display images of government torture chambers.

The exhibition opened in mid-May this year with a series of panels featuring people whose lives were intertwined with the Amin regime. The opening panel featured politicians who served in Amin’s cabinet; on another night, journalists who covered his government discussed their work; on a third evening, we heard from people who had lost loved ones in the hands of his thugs.

We had intended to convene a fourth panel where Idi Amin’s family members would discuss their memories of their father. But 15 minutes before we were to go on the air, they announced that they would no longer participate. They thought the exhibition didn’t adequately acknowledge their father’s achievements.

Their reluctance to speak highlights the tensions that undergird public discussion around the Amin regime today.

Derek R. Peterson, professor of History and African Studies, University of Michigan and Richard Vokes, associate professor of Anthroplogy, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.