The rise and rise of the literary festival in African cities

On June 1, 1962, black writers and other intellectuals from all over the world converged on Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda for the Conference of African Writers of English Expression. They were there to discuss the legacy of colonialism and what African literature should look like in a continent that was rapidly getting independent. The conference led to a schism in African letters with those from former English colonies at odds with the Francophone delegates who espoused the Negritude movement. The Anglophone writers didn’t feel that this movement went far enough for newly independent nations.

On June 1, 1962, black writers and other intellectuals from all over the world converged on Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda for the Conference of African Writers of English Expression. They were there to discuss the legacy of colonialism and what African literature should look like in a continent that was rapidly getting independent. The conference led to a schism in African letters with those from former English colonies at odds with the Francophone delegates who espoused the Negritude movement. The Anglophone writers didn’t feel that this movement went far enough for newly independent nations.

Since then, there have been many literary gatherings with a mixed bag of results for readers and writers across the continent. Perhaps as a result of the fallout from that event in 1962 and more practical communication purposes, the gatherings have tended to host writers from the same European language group and, at best, a token writer or two from the others.

Thus you will have a festival with mainly English, French or Arabic speakers and one from the other groups. Portuguese speaking Africa, as have been writers in mainly African languages, has been estranged from all of these groupings. The most successful of these literary shindigs have been Northern African nations which usually have state support. The Cairo, the Casablanca, and the Algiers festivals, for instance, have been hugely successful with millions attending to meet authors and make purchases at the stands of publishers in the last few years. In Sub-Saharan Africa however, literary gatherings, usually called “book fairs” have been publishing industry affairs where players meet to do deals on distribution and other industry-related discussions away from the reading public.

Until recently.

In the last decade and a half, there has been a rise of a new kind of literary festival where writers and readers interact over their text and how it affects their lives. These festivals, now in their dozens, were founded for different purposes and have achieved a lot for the countries or individuals who attend.

One of the older gatherings is “Time of the Writer” that happens annually in the coastal city of Durban, South Africa. The festival, run by the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal’s Centre For Creative Arts has hosted dozens of some of the biggest writers in World Literature since its commencement in 1996. Quizzed on the increase of festivals in the last decade and a half, Centre For Creative Arts’ Siphindile Hlongwa says that there has been a rise in a love for all things African.

“There has been a growth in the love of our authentic narratives from Africa, and a hunger for spaces to listen and support African voices and the importance of archiving, publishing and reading,” Hlongwa stated.

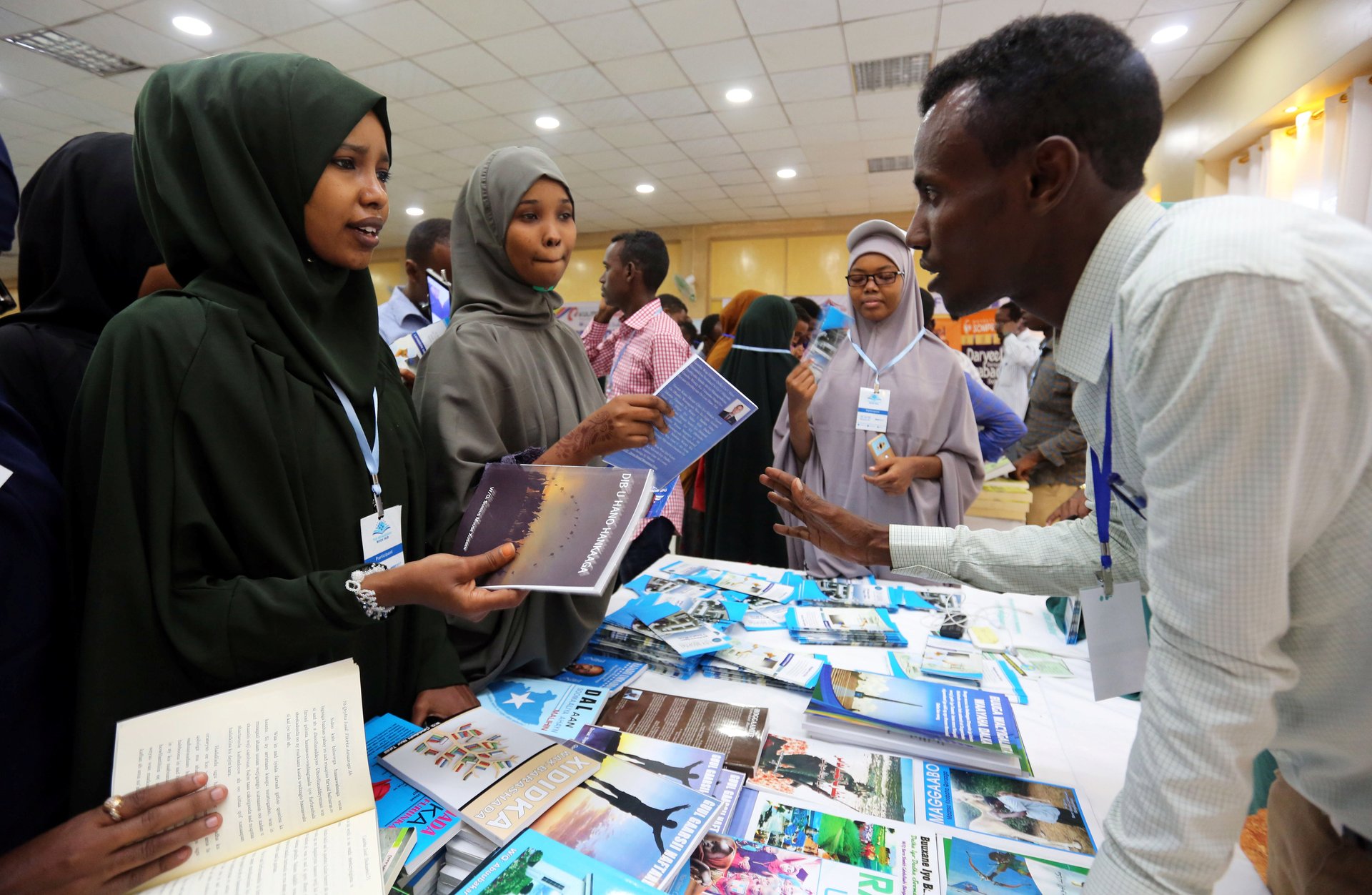

Another of the longer running festivals is the Hargeysa International Book Fair founded in 2008 by Somaliland academic Dr Jama Musse Jama. The festival, which happens annually in Hargeysa, the capital of the self-declared nation of Somaliland, has been vital in the nation’s push to be recognized as autonomous. This has been strategically done through making countries like Nigeria, Malawi, Kenya, Rwanda, Egypt, and South Africa the focus countries for each year of the festival.

“Hargeysa International Book Fair has been a manifestation of the need for institutional cultural enablers rooted in the African context instead of simulating the West where literature production is in sync with the commercial side of art production,” says festival founder Dr Jama. “It became a flagship status for a nation’s pride in culture and art.”

The fair while being vital in Somaliland’s hopes for international recognition, has also been handy for the country’s citizens.

“The book fair became a window open to the world where young people have access to world literature,” Jama says.

The Gambia hosts the Mboka Festival founded by Kadija George which has gone a long way in highlighting that the West African country has a literary community that wants to be recognized internationally.

“The festival also brings visitors to the country,” says Ms George. “There is more to The Gambia than sun, sea, and sand.”

Another festival making waves is the Lagos-based Ake Arts & Book Festival, founded in 2013 by Lola Shoneyin, the author of The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives. The festival is one of the most eagerly anticipated on the continental literary calendar with thousands making their way to Lagos annually.

“Festivals bring creatives closer to those who consume their work so it’s usually quite a joyous rendezvous. But beyond that, there is a palpable sense of community with which people create these safe spaces,” says Lola Shoneyin. “I have felt it in Lagos, in Soweto, in Gaborone and most recently in Kigali.”

This sentiment of community is shared by Keikantse Phele, one of the founders of the Gaborone Book Fair, which started operating in Botswana in 2018.

“Festivals enable locals to appreciate their own people. They give a spirit of togetherness, sharing and networking among African authors and those in the literary ecosystem,” she states. “They also give a space for emerging talent, and the festivals as they convened with different themes, then are able to locate and use African authors for such.”

Some of the problems of the past are still evident as festivals tend to have a majority of speakers from one language group like was in the wake of the Makerere Conference. For the future, the festivals need the support of all organizers and writers as they seek the long term drive for African patrons and not for ‘outside’ funders to survive and thrive. While there are still challenges, ultimately the literary community across the continent has been changed by new younger audiences.

“Young people are looking for truths that speak to them. Politicians and leaders on the continent are a let-down. Millennials seek truths that can move them, and move them forward. The African creative is the last bastion of truth and hope,” Shoneyin says.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox