Nigeria is finally turning to telcos to drive financial inclusion through mobile money

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, with a population of some 200 million people, has long been one of the big hopes for mobile money and financial inclusion evangelists. And yet, until very recently, it seemed its government and regulators were reluctant to listen to the proverbial “good word.”

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, with a population of some 200 million people, has long been one of the big hopes for mobile money and financial inclusion evangelists. And yet, until very recently, it seemed its government and regulators were reluctant to listen to the proverbial “good word.”

Financial inclusion in East Africa has been significantly impacted by the wide adoption of mobile money services—led by Kenya— but the uptake has been slow in Africa’s two largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa. While South Africa’s more advanced economy often treats mobile money as a “nice to have”, the situation in Nigeria is quite different. There, just 40% of people have bank accounts, so the economy would likely get a boost from the expansion of mobile money services.

The regulatory caution and conservatism often blamed for holding Nigeria back finally looks set to change with the central bank reversing a longstanding stance on declining to issue mobile money licenses to telecoms operators.

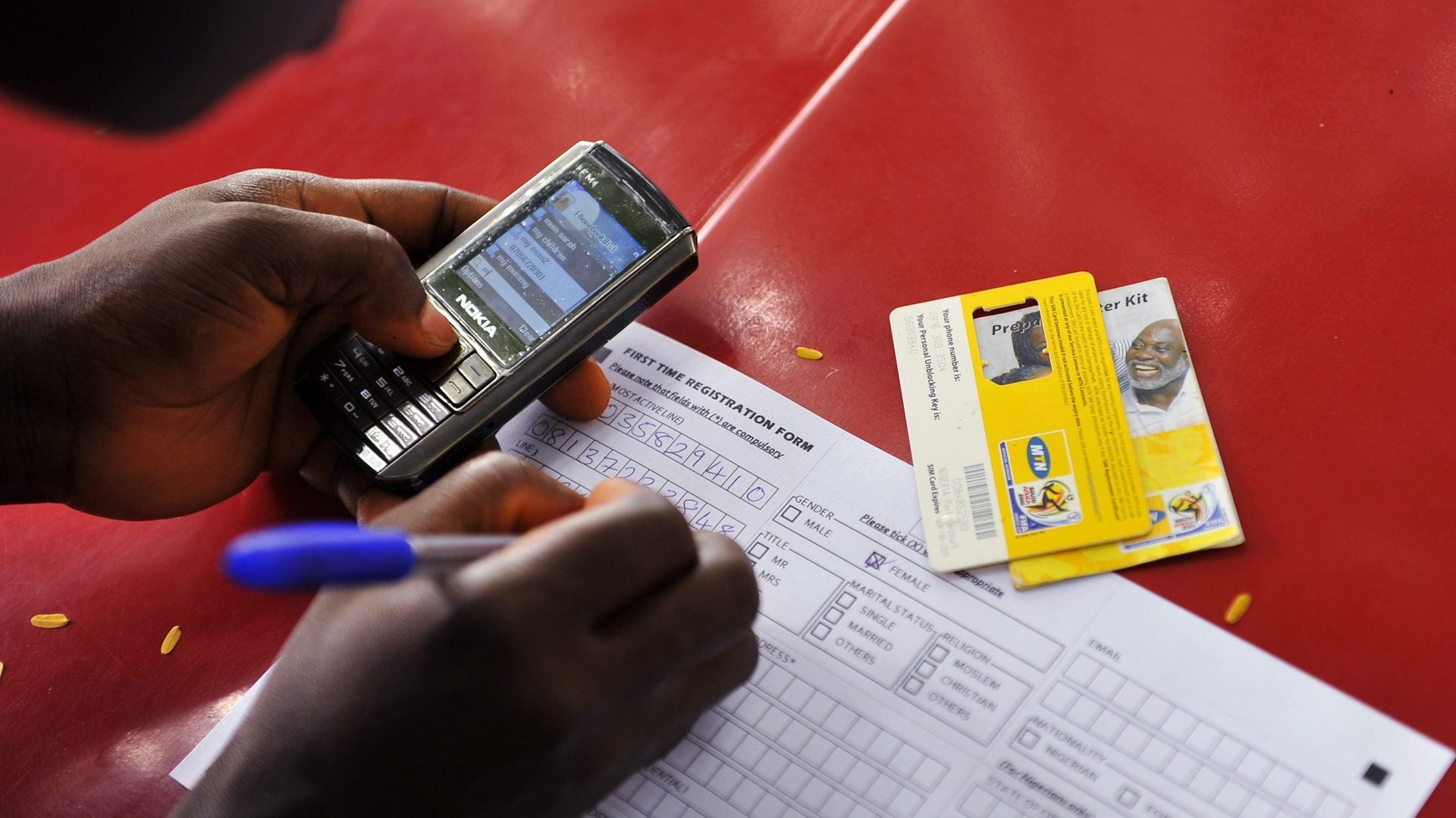

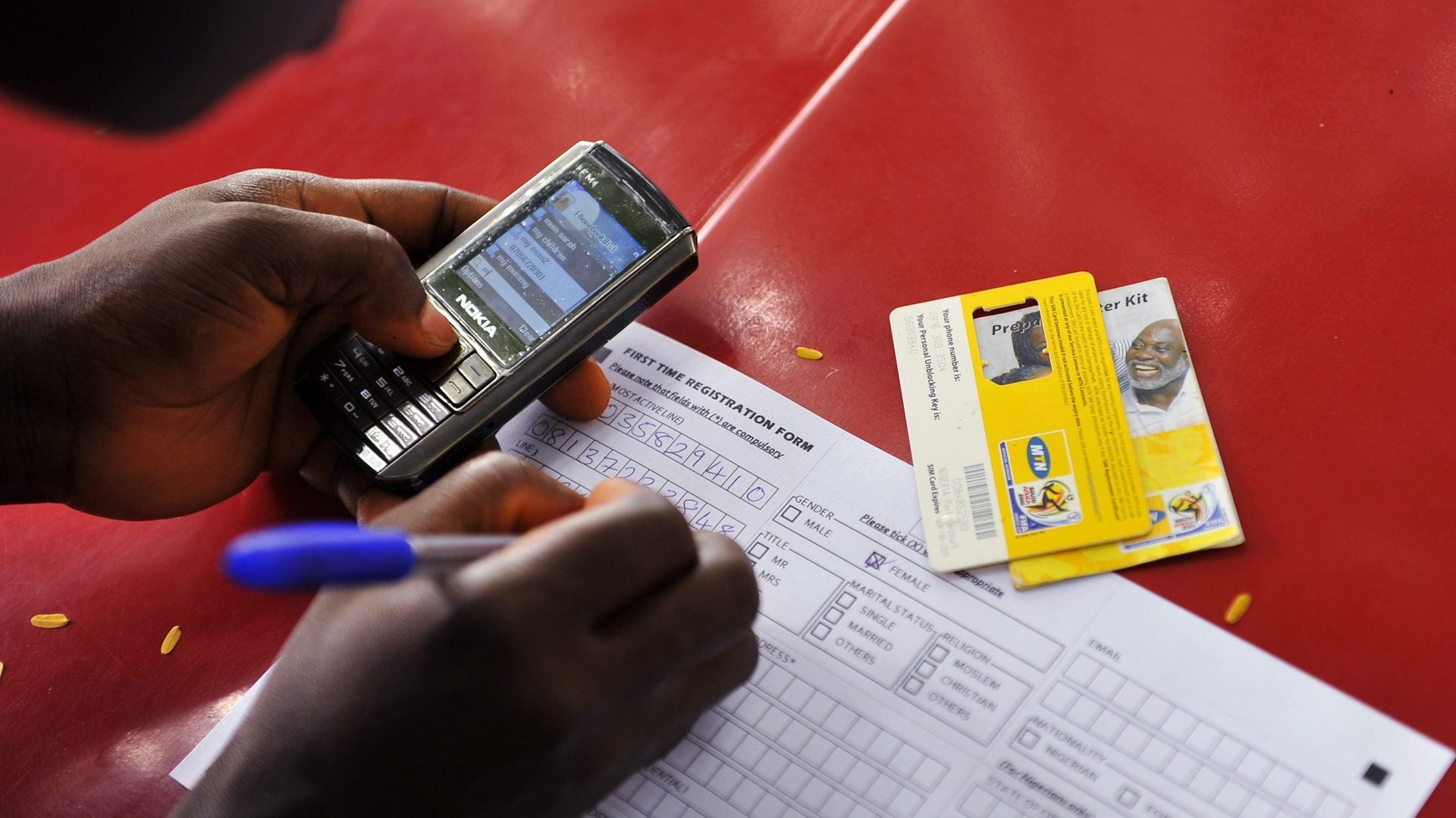

In the wake of the central bank’s change in tack, MTN, Nigeria’s largest telecoms operator, with more than 60 million customers, has launched its MoMo Agent mobile money service. And, on the back of a $1.2 billion funding boost last year, Airtel Nigeria, Nigeria’s third largest operator, is expected to follow suit. 9Mobile and Globacom, the country’s two other major operators, have also reportedly been issued licenses to become payment service banks.

The Central Bank of Nigeria explains its decision to license mobile operators as being rooted in its policy goal of boosting financial inclusion, hoping to replicate the experience of countries like India and Kenya. There’s evidence of what’s possible, especially in Kenya, where mobile money services have helped lift about 194,000 households out of extreme poverty, a new World Bank report says.

The overarching theory for the Nigeria’s central bank is simple: telecoms operators who already reach and offer their products to millions of people in remote, rural parts of the country (which are typically home to unbanked people) can also offer them financial services and boost inclusion.

The need to boost financial inclusion is not a economic development vanity project for Nigerian policy makers. Up to 65% of the economy is still entrenched in the informal sector, as the government is pressured by multilateral lenders and economic common sense to diversify from its reliance on oil revenue. It will need to—at a bare minimum—significantly expand its tax base. This has always been particularly difficult in a cash-based informal economy.

Market shake-up

The entry of major telecoms operators into the mobile money space offers them a chance to tap into and shake up an industry that’s long held promise given certain indices that suggest there’s potential for success. A majority of Nigeria’s vast population remains unbanked despite the best efforts of government and the traditional banking industry. Mobile phones have also become ubiquitous far beyond urban centers, and can be deployed as tools for financial inclusion as has been done elsewhere.

“The business case for banks to continue to roll out branches is no longer there,” says Tajudeen Omokide, a senior manager at Y’ello Digital Financial Services, MTN’s financial services subsidiary. “Looking at the services people are doing in banking halls viz a viz the cost of infrastructure and security situation, a bank will gladly have customers served at an agent point.” As such, rather than solely rely on its existing distribution points of mobile phone and airtime retailers, Omokide says building an independent agent network for its financial service offerings is a “fundamental pillar” of MTN’s strategy. MTN’s MoMo Agent service will let users send and receive money both to unbanked persons and registered bank accounts through agents as well as pay bills.

But MTN won’t be a pioneer in that regard as existing services like Paga, a 10-year old mobile money service, has already built a 23,000 strong agent network. For its part, MTN says its roadmap for building an agent network will focus strongly on going beyond urban centers and is committing to having agents in each of Nigeria’s 774 local governments to ensure nationwide presence.

Like most telecoms operators, MTN will have the advantage of brand recognition and familiarity, a tool that helps attract not only customers but agents as well: in its first three months, MTN MoMo Agent has garnered over 15,000 agents, Omokide says. (MTN’s agents also serve other payment services as current regulation does not allow exclusivity in agent banking.)

The possibility of MTN MoMo Agent having impact on the same scale with M-Pesa in Kenya will have to wait though as there’s currently one key difference between both services: given its current license, MTN MoMo Agent can only offer financial services through its agent network rather than offering users the convenience of doing transactions on their phones via their individual mobile money accounts. But industry insiders say it’s only a matter of time before MTN receives a payment service bank license which allow it to offer more personalized services.

Old against new

While the central bank will play up the long-term benefits of boosting financial inclusion with its new regulations, on paper, the move represents an existential threat for long-time players in the financial services space. Banks are limited to serving only banked customers while most standalone mobile payments services do not have resources—in cash, brand recognition and reach—to match major telecoms operators.

To bridge the gap, some standalone new services, like OPay, are taking an expensive route. Rather than depend solely on media campaigns or organic growth, the mobile money and payments service started by Opera has massively subsidized rides on ORide, its bike-hailing service, to popularize the money money platform among mass market users. It’s a strategy that comes at the expense of short-term returns or profitability for ORide. But it’s proving enough to attract major backers regardless: OPay raised $50 million from an assortment of Chinese investors earlier this year.

For his part, Tayo Oviosu, chief executive of Paga, says the jury is still out on whether telecoms operators can truly dominate in large countries like Nigeria and points to the success of services unaffiliated with telecoms operators in other countries as encouragement.

“In large countries, we have not yet seen a single mobile operator be the most successful [mobile money] company. In India, it’s PayTM, in China, it’s Tencent and Alipay while in US it’s Paypal, Venmo,” he says.

But as they enter the space in Nigeria, Oviosu points to the dangers of telecoms operators being able to either hobble other competing mobile money services that require their networks to operate or conducting targeted advertising campaigns given their advantage of access to subscribers’ phone habits. (Oviosu claims Paga users have already been subject to targeted advertising by MTN).

“That’s a risk that the central bank needs to clamp down aggressively on because [it can result in] telecoms operators doing anti-competitive things,” he says. Given current regulation guidelines, Oviosu says existing players “are not protected” from those dangers.

While Oviosu accepts the central bank’s decision to allow telecoms operators offer financial services through mobile money was a logical next step, he suggests some fundamental requirements for inclusion are not yet in place. “The first ingredient to financial inclusion is identity and we’ve just not solved that in Nigeria,” he says. Indeed, an ongoing national identification card drive has been beset by processing delays and hiccups with data collection.

Overall however, Oviosu says the apparent eagerness of MTN and other operators to tap into the industry represents some validation for existing operators. As he puts it: “Everyone is now seeing an opportunity that we have seen for a while.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox