How Africa’s richest woman bought her way out of scrutiny from Western banks

In 2013, Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s richest woman, was facing a major headache: She had become toxic to Western banks.

In 2013, Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s richest woman, was facing a major headache: She had become toxic to Western banks.

“These guys hear about Isabel and they run like the devil from the cross,” read an email sent the next year by a business manager for dos Santos, daughter of the then-president of Angola, who led one of the world’s most corrupt regimes. Last month, the Angolan government, which is no longer controlled by the dos Santos family, froze Isabel dos Santos’ assets, alleging that she and her husband caused the state to lose more than $1 billion.

Dos Santos denied the allegations as “politically motivated.”

But the Luanda Leaks, a major investigation by dozens of media organizations published today and based on a trove of more than 700,000 emails, contracts, and other documents, reveals the inside story of how dos Santos siphoned hundreds of millions of dollars in public money out of one of the poorest countries on the planet and into a labyrinth of more than 450 companies, many based in tax havens.

The international banking system has been a major actor in the trials and travails of her empire. After the 2008 financial crisis and a series of money-laundering scandals, regulators turned up the heat on big banks. The banks responded by hiring thousands of compliance officers, who began cutting off clients who may have taken part in unethical or illegal business practices. Dos Santos fell prey to the compliance officers’ hatchets and was turned down by giants like Citigroup, Barclays, and Deutsche Bank, the files show.

Exile from the global banking system is a nightmarish prospect for any international businessperson. It stifles your ability to get credit to fund new projects or invest in foreign businesses. It also makes it much harder to enjoy your riches in the West.

But dos Santos seems to have sidestepped the crackdown by simply buying large stakes in banks for herself. Her case shows how the global financial system tried and failed to sideline a billionaire accused of financial crimes. And it ultimately proves a truism about global capitalism—that if you’re rich enough, there are ways around just about every regulatory hassle.

“We used to say one of the best ways to launder money is to buy the bank,” said Debra LaPrevotte, a former senior FBI agent who helped set up its kleptocracy program. “Whenever you have a complicit bank, it makes it that much easier for kleptocrats to move illicit funds.”

The two Portuguese banks dos Santos part-owned provided at least three crucial services to her and her associates. One opened bank accounts for offshore shell companies so she could buy European real estate. Another signed off on enormous and suspicious payments. And both extended large loans.

Quartz outlined its findings to five anti-corruption and compliance experts, all of whom said dos Santos’ activity should have raised red flags for money laundering or conflicts of interest within those banks’ compliance departments.

Quartz members support high-quality, investigative journalism like this in a time when we need it most. Become a member and help build Quartz’s future.

The Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa, a Paris-based advocacy and legal group, originally passed the leaked files—known collectively as the Luanda Leaks—to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). ICIJ then shared the files with reporters from 36 news organizations in 20 different countries, who spent 8 months combing through them.

Dos Santos has denied any wrongdoing. She said the leak was part of a “concerted attack” on her by the new Angolan government. “[They] have decided to go and hack my offices, leak certain documents to investigative journalists, and then to put these questions forward,” she told the BBC, a Luanda Leaks partner.

The squeeze

Citi was the first big bank to start dropping dos Santos-linked businesses.

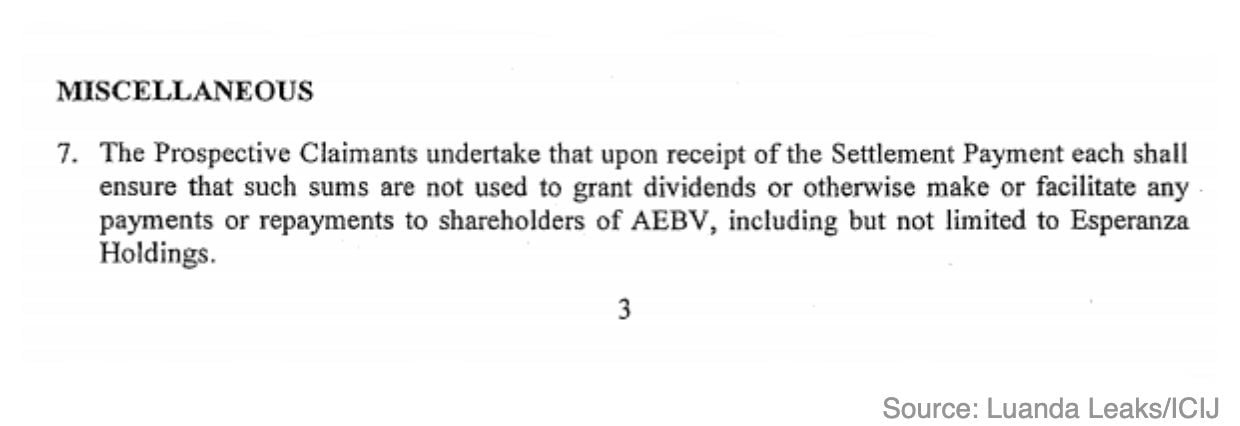

In April 2012, US regulators handed the bank a cease-and-desist order for what they said were “deficiencies” in its anti-money-laundering program. A month later, one of Citi’s subsidiaries backed out of a financing deal for Amorim Energia BV (AEBV), a Dutch holding company whose shareholders included Esperaza, a firm part-owned by dos Santos’ husband, Sindika Dokolo, and Angolan state oil company Sonangol. Citi cited Esperaza as its reason for pulling out, according to minutes from two AEBV board meetings found in the leaked files. AEBV threatened to sue Citi, which agreed to pay a $15 million confidential settlement—on the condition that none of that money would go to Esperaza.

A year later, Barclays followed Citi’s example, canceling a deal with AEBV that aimed to raise nearly $400 million in financing. The bank cut ties in an email sent late the night before the deal’s planned announcement. After threatening another lawsuit, AEBV’s board accepted a roughly $250,000 settlement from Barclays, according to the meeting minutes.

Dos Santos’ troubles continued the next year. In February 2014, a dos Santos employee told a colleague that Spanish bank Santander had designated her a Politically Exposed Person (PEP), a term used by financial regulators for public officials and their family members who may be vulnerable to bribery or corruption.

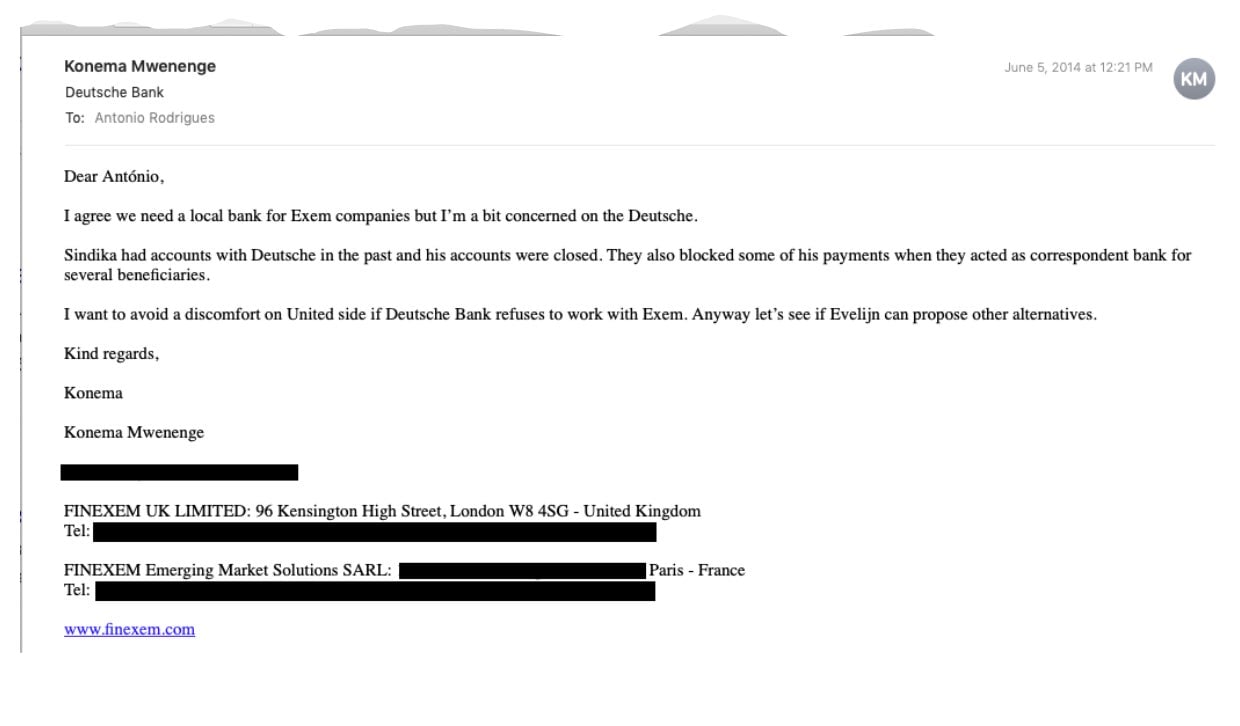

Even Deutsche Bank, which US and UK authorities fined hundreds of millions of dollars in 2017 for allegedly laundering Russian money and violating economic sanctions, avoided dos Santos and her husband. When Dutch bank ING terminated accounts held by three companies tied to the couple in 2014, Deutsche refused to take them on, emails from dos Santos employees show. Dokolo, dos Santos’ husband, had previously held accounts with the German giant but Deutsche shut them down too, according to employee emails found in the leaked documents. Esperaza also held an account with Deutsche until around 2015, when the bank again forced it to close.

After the rejection from Santander, the dos Santos employee turned to a Portuguese proverb to express frustration at being denied by bank after bank. “The people are right: From Spain, neither good wind nor good marriage,” he wrote in an email. The expression alludes to a history of unsuccessful matrimonies between the two countries’ royal families and the harsh winds that sweep towards Portugal from its neighbor.

Citi, Barclays, Santander, and Deutsche declined to comment on questions related to the Luanda Leaks. A Deutsche spokesperson said the bank carefully monitors risks related to Politically Exposed Persons.

A new banking empire

But all was not lost for dos Santos.

She had started her own banking empire in 2005, when she co-founded Banco BIC in Angola. BIC swiftly became a major player, in part by lending hundreds of millions to her father’s government. In 2008, the bank expanded to Portugal, giving it a foothold in Europe. By 2014, her stake in BIC had grown to 42.5%, and the bank was opening offices in Mozambique, Cape Verde, and Namibia.

The next year, she bought a 9.7% stake in Banco BPI, now Portugal’s fifth-biggest bank by assets. Decimated by the Eurozone crisis, Portugal was more than willing to take then-booming Angola’s riches, and by 2014, dos Santos had accumulated an 18.6% stake in the bank, becoming its second-largest stakeholder. She sold her shares in 2017, when Spain’s CaixaBank took control of the Portuguese lender.

As well-known banks ran away, BIC and BPI proved ready and willing to work with dos Santos and her husband.

Neither BIC nor BPI responded to requests for comment. BIC Portugal (now named Eurobic) told Reuters last week it acted “in rigorous respect” of laws relating to shareholders and Politically Exposed Persons. The bank said it had made “significant investment in the prevention of money-laundering or financing of terrorism” since 2016, at the central bank’s behest.

Real estate, real accounts

In 2014, dos Santos created a company called Silaba Real Estate in the Isle of Man, a UK tax haven, with the aim of investing in London property. For the company to be of any use, it needed a bank account. That wouldn’t be easy given her political connections.

“We can attempt to open a bank account for the company in the Isle of Man, but given the nature of the client this might prove challenging,” John Murphy, an Isle of Man-based company formation agent, wrote in an email to her lawyers.

He suggested approaching Standard Bank in South Africa, which had a branch on the island. When the application was held up by due diligence checks on dos Santos, her people turned to Banco BPI, the leaked files show. BPI agreed to open an account for a shell company owned by its second-biggest shareholder, even though the bank had no presence in the Isle of Man.

It’s “very uncommon” for a bank to open an account for a shell company in a tax haven where it has no presence, said Michael Hershman, a co-founder of Transparency International and CEO of the Fairfax Group, a compliance consultancy. “That’s a very risky proposition. You’re not going to find many established banks that have strong Know Your Customer rules who would take that sort of risk.”

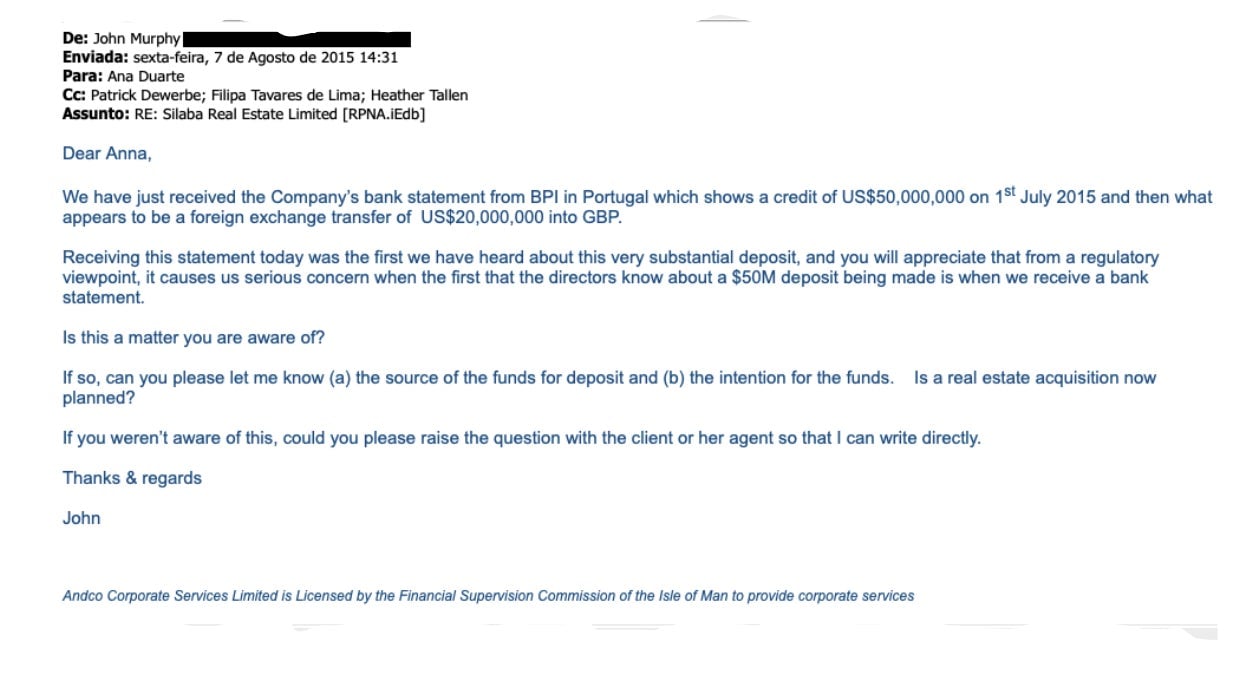

A year after the account opened, Murphy spotted an alarming development. Out of nowhere, $50 million had appeared in the BPI account. He wrote a worried email to dos Santos’ lawyers. “Receiving this [bank] statement today was the first we have heard about this very substantial deposit, and you will appreciate that from a regulatory viewpoint, it causes us serious concern when the first that the directors know about a $50M deposit being made is when we receive a bank statement. Is this a matter you are aware of? If so, can you please let me know (a) the source of the funds for deposit and (b) the intention for the funds,” he wrote.

After receiving the email, one of the lawyers wrote privately to a colleague, “We have to talk about this.” It’s unclear from the files what happened to the money, where it came from, or whether Silaba ever bought London real estate. Murphy, who didn’t respond to a request for comment, soon resigned.

Dos Santos did use a BPI account to buy at least one major European property—a floor of a luxury building in downtown Monte Carlo, which cost about $60 million. The leaked files show that BPI opened an account for Athol Ltd, a Malta-based holding company through which dos Santos bought the property. Company records show that dos Santos loaned Athol about $60 million over several transactions between 2012 and 2015 to buy the property. But it’s unclear from the documents where she originally held that money or how she earned it.

Authorities in Monaco are investigating dos Santos, her husband, and her father on suspicion of money laundering, Portuguese newspaper Expresso, a Luanda Leaks partner, reported last week. (Dos Santos declined to comment to Expresso.)

The transactions made to buy the real estate are “consistent with money laundering on this scale,” LaPrevotte said. Hershman agreed: “BPI is going to get slammed for this—I’m very shocked and surprised. There really is no excuse for them assisting her in this manner.”

Real estate is seen as particularly vulnerable to laundered money, and it is up to banks to be the “first line of defense” against dirty money entering the system, said Shruti Shah, CEO of the Coalition for Integrity, an anti-corruption nonprofit. “The real estate industry doesn’t seem to do any due diligence on the identities of purchasers [or on their] funds, so it’s a perfect storm where everybody thinks it’s someone else’s responsibility to do it or turns a blind eye.”

Dokolo defended the use of holding companies in tax havens in an interview with Radio France International, a Luanda Leaks partner. “It is very difficult for someone from Angola or the DRC, which are countries completely blacklisted on European markets, to open a bank account on European soil. If you are like me, a personality who has been politically exposed since 2001, it is about the impossible,” he said. “I can be criticized for using financial vehicles located in tax havens, but is that illegal? Firstly, I do not use them for investments in Europe. I only use them because Angola does not have a double taxation agreement. There is no reason for me to pay my taxes twice.”

Loans: The Efacec imbroglio

In 2015, another dos Santos-owned Maltese holding company, named Winterfell 2, spent about $220 million on a roughly 65% stake in Portuguese engineering company Efacec. Dos Santos raised around $175 million in loans to finance the purchase, of which around $150 million came from a handful of Portuguese banks, including BPI, according to an internal investigation by the Bank of Portugal, the country’s central bank.

Banks in dos Santos’ empire helped finance the deal, taking actions that should have raised red flags for money laundering and conflicts of interest, experts said.

A mysterious $28 million came from a BIC Portugal account. The Bank of Portugal investigation was unable to get to the bottom of where exactly the money came from. BIC Portugal told the Bank of Portugal it didn’t know where the loan originated, but that Winterfell’s Angolan sister company had borrowed the money in Angola and sent it to its account with BIC Portugal. However, the money seems to have been actually lent by BIC Angola to both Winterfell 2 and Winterfell Angola, according to a draft loan agreement found in the leaked files.

Last November, Ana Gomes, a Portuguese diplomat and prominent former member of the European parliament, called for an investigation into BIC’s role in the purchase in a letter sent to officials at the European Commission and European Central Bank and obtained by Expresso and shared with Luanda Leaks partners. Gomes alleged the $28 million was one of several cases in which BIC laundered money for dos Santos. In an interview with the BBC, Gomes alleged that the Portuguese banks involved “completely neglected” that dos Santos is a Politically Exposed Person and ignored conflicts of interest surrounding her stakes in two Portuguese banks. Dos Santos denies Gomes’ allegations and sued her for slander. A Lisbon court threw the case out this week, without ruling on whether the allegations are true.

BIC Portugal’s acceptance of the $28 million from BIC Angola without knowing where the money came from is a “pretty high risk transaction” that “should have been subject to very significant documentation,” said Graham Barrow, an anti-money laundering expert who has worked for Deutsche Bank, HSBC, and Britain’s financial services regulator.

Dos Santos was a non-executive director of BIC Portugal when the transfer happened, according to a report by her lawyers found in the files. The Bank of Portugal report concluded that BIC Portugal’s “internal control system is NON-EXISTENT.”

Separately, BPI loaned another $28 million to Winterfell, offering a 16.3% stake in Efacec as collateral, the Bank of Portugal investigation and other documents show. The bank had a “clear conflict of interest” in lending money to one of its main shareholders, Barrow said. Hershman said it’s “highly uncommon” for a major bank to make this kind of loan to a shareholder.

Payments: The Matter matter

A BIC Portugal official signed off on payments worth $58 million that are at the center of some of the most jaw-dropping corruption allegations against dos Santos, which date from the time of her dismissal as the head of Sonangol, the Angolan state oil company, in November 2017. Angolan law enforcement is investigating large bank transfers made in November 2017 from an account Sonangol held with BIC Portugal to a company in Dubai, the country’s attorney general said in a joint interview with Luanda Leaks partners.

Portuguese authorities said this month they are investigating embezzlement claims against dos Santos, following a complaint from Gomes about the transactions and the Efacec acquisition. Dos Santos denied the allegations and promised to fight them in court.

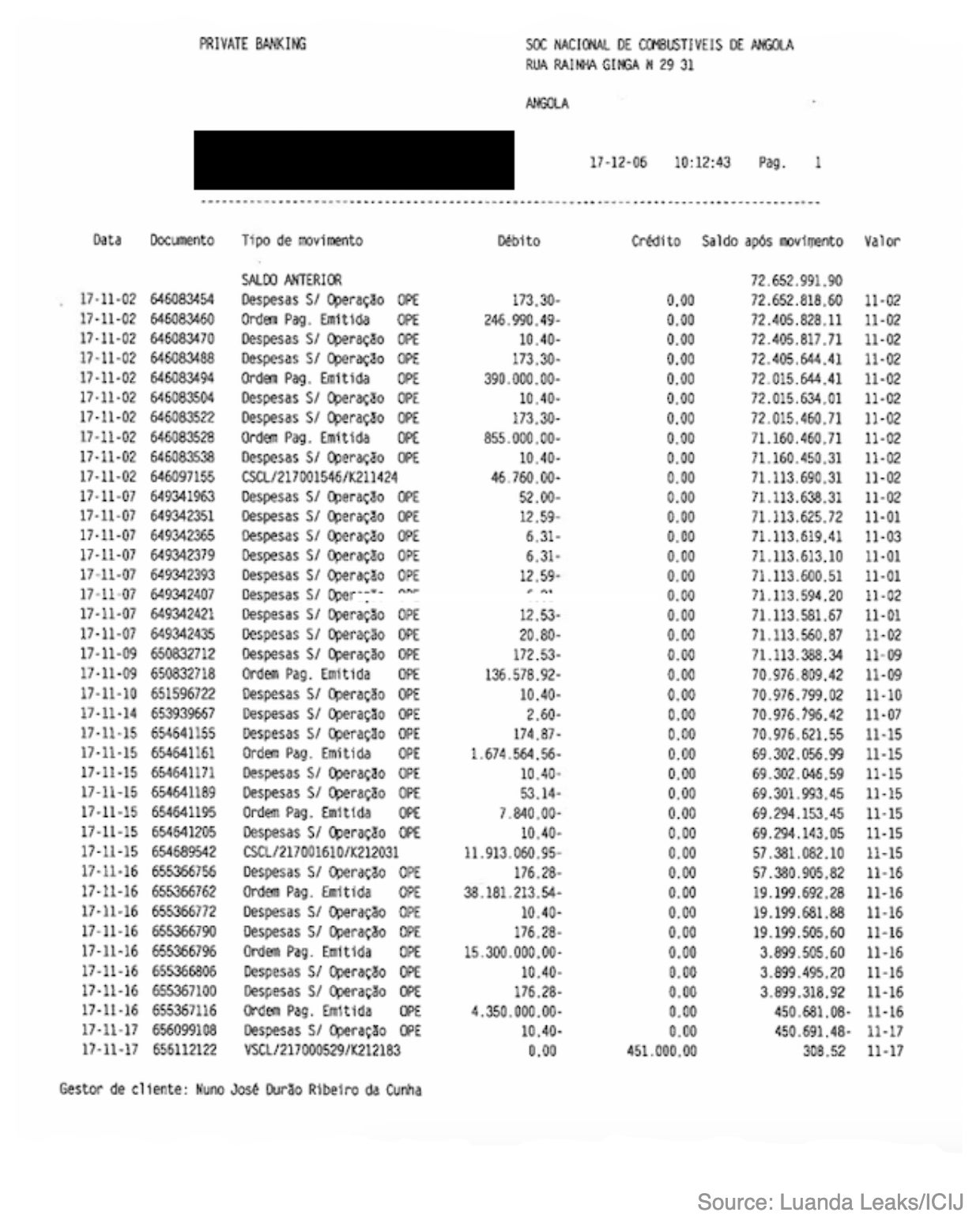

On Nov. 16, the day after dos Santos was fired, Sonangol UK made three payments worth $57.8 million in total to Dubai-based Matter DMCC, according to files obtained by Expresso. Once the transfers had gone through, Sonangol UK’s account was overdrawn, a bank statement shows.

Matter’s owner was dos Santos’ longtime business partner Paula Oliveira. Dos Santos’ key aide, Mario da Silva, was listed as a director of the company. The day before dos Santos was fired, an employee at Fidequity, a management services firm at the center of dos Santos’ empire, emailed a contract between Matter and Sonangol to Sonangol, the files show. The contract was signed by Oliveira.

In an interview with the BBC, dos Santos denied that she was looting the company on her way out the door, saying Matter was in charge of subcontracting major consultancies that worked for Sonangol. She insisted she couldn’t have been planning to steal the money because she didn’t know she would be fired. “I did not know that I would be dismissed on the 16th of or whatever date of November it was,” she said. “I’m not clairvoyant, I don’t know what goes in the mind of the president and, you know, I have no reason to believe that I would be dismissed on that particular day.”

However, one of the orders to make the payments was emailed to BIC, with dos Santos copied, on the evening of Nov. 15—around five hours after the press reported she had been fired. The payment order was sent by Sarju Raikundalia, whom dos Santos had hired to manage Sonangol’s finances, and who had also been fired around five hours earlier. Nonetheless, BIC Portugal’s head of private banking, Nuno Cunha, approved the payment, the files show.

The 55 invoices ostensibly provided by Matter for the roughly $58 million are eyebrow-raising, according to an investigation into the transfers by Sonangol. Thirty-six of them were dated before Matter’s contract with Sonangol began, the investigation shows. At least 19 more were created after dos Santos was fired and seemingly backdated to look like they were made beforehand. Two invoices, both for €676,399.97 (around $760,000), are almost identical, and another, for €472,196.67 (around $530,000) doesn’t explain what the expenses were.

Dos Santos said she was not familiar with the invoices when shown them by a BBC Africa journalist. In a letter to ICIJ, her lawyers said the company wasn’t owned by dos Santos or her husband, and said she abstained on a board vote over whether to give Matter the contract.

Through her UK lawyers, Oliveira denied wrongdoing and said dos Santos had no management or ownership role in Matter. Any implication Oliveira was “some sort of stooge sitting as proxy for Mrs. dos Santos” is false, the lawyers said in a letter. The invoices were sent at the last minute in an effort to settle accounts with Sonangol, the lawyers said.

Cunha didn’t answer questions for comment on why he signed off on a payment instruction sent by someone who had been fired hours earlier, or why he accepted invoices that appear to have been backdated.

Lapses in Lisbon

Dos Santos’ alleged money laundering through Portuguese accounts shares similarities with previous European financial scandals, where allegedly corrupt actors used less-scrutinized banks in poorer EU countries like Latvia and Estonia to shift hundreds of billions into Europe’s banking system. From there, they can move it around the world with comparative ease.

The combination of Portugal’s debt crisis and its regulators’ history of lax enforcement made Portugal’s banking system an easy target, Barrow said.

“Banks within Portugal were under significant pressure to ease their liquidity problems, and a highly valued and valuable customer would be very difficult to turn away when the bank itself was under significant pressure to survive,” he said. “The cynic in me says many banks at the time looked at this business, and said, ‘Whatever the fines are, our regulator doesn’t have a history of making huge fines and what we’re going to make out of this is bigger than the potential fine.’ It wouldn’t be overly surprising if a conversation along those lines happened.”

BIC received no fines or charges over its work for dos Santos. The Bank of Portugal said that, in response to the money-laundering allegations, it had imposed a “segregation” strategy on BIC, to minimize its exposure to BIC Angola and BIC Cape Verde. “Eurobic is subject to close monitoring,” it said in a statement. Dos Santos has left the board, and various independent board members with no connections to shareholders have joined, the Bank of Portugal added. It said it has conducted on-site inspections, and imposed a “large set of injunctions” to strengthen BIC’s anti-money-laundering controls, including a new compliance officer and a board member in charge of anti-money laundering. (BIC told Reuters last week it saw a recent inspection as “part of the normal supervision process.)

Nonetheless, for Shah, the case speaks to a “long-held suspicion”: That “anti-money-laundering enforcement outside of a few countries does not really exist.”

ICIJ’s Douglas Dalby contributed to this report.