Photos: Burkina Faso’s contemporary dance festival turns the discourse away from terror

Burkina Faso’s annual contemporary dance festival plied, rolled, tumbled and convulsed, barefoot and in ballet slippers, under spotlights and on the streets, throughout the capital Ouagadougou last week.

Burkina Faso’s annual contemporary dance festival plied, rolled, tumbled and convulsed, barefoot and in ballet slippers, under spotlights and on the streets, throughout the capital Ouagadougou last week.

“We can’t stop living because of terrorism,” said Irène Tassembédo, the event’s organizer, who runs an experimental dance school on the outskirts of the city.

Burkina Faso has made headlines for terrorist attacks in recent years, yet international film and arts festivals continue to be held in Ouagadougou and the western city of Bobo-Dioulasso.

“When you listen to the press you think that it’s like bang, bang, bang—yet here we are,” said Tassembédo, as people trickled into the open-aired theatre for a performance.

Now in its eighth year, the Festival of International Dance of Ouagadougou (FIDO) is the only major annual contemporary dance festival on the continent, drawing troupes and solo performers from West Arica, Europe and the United States. A smaller annual festival in Bamako, Mali’s capital, began on Jan. 25 at the same time.

State travel advisories from Western nations have colored the map of Burkina Faso in red, as the number of attacks by armed groups continue to rise. This year some dance troupes decided not to come to the festival.

“I understand that people are afraid, but if you love something and you love the people, you should love them with all of their problems,” said Tassembédo.

Tassembédo started her career as a traditional dancer before moving to Dakar to study contemporary dance in late 1970s at the famous École Mudra created by avant-garde French dancer Maurice Béjart. She danced with Germaine Agoncy, a French-Senegalese dancer, who, along with Tassembédo, is also one of the founding figures in modern contemporary dance in Africa. Senegal and Burkina Faso, with their rich arts and festival scenes, were fertile ground for contemporary dance. Even in recent years foreigners regularly travelled to Burkina Faso to study both traditional and modern dance.

Nowadays, festivals focused on contemporary dance unfold in Cameroon, South Africa, Mozambique and Mali every other year. FIDO is among the best known and performances are often centered on political themes—this year “stigmatization” was the anchoring concept.

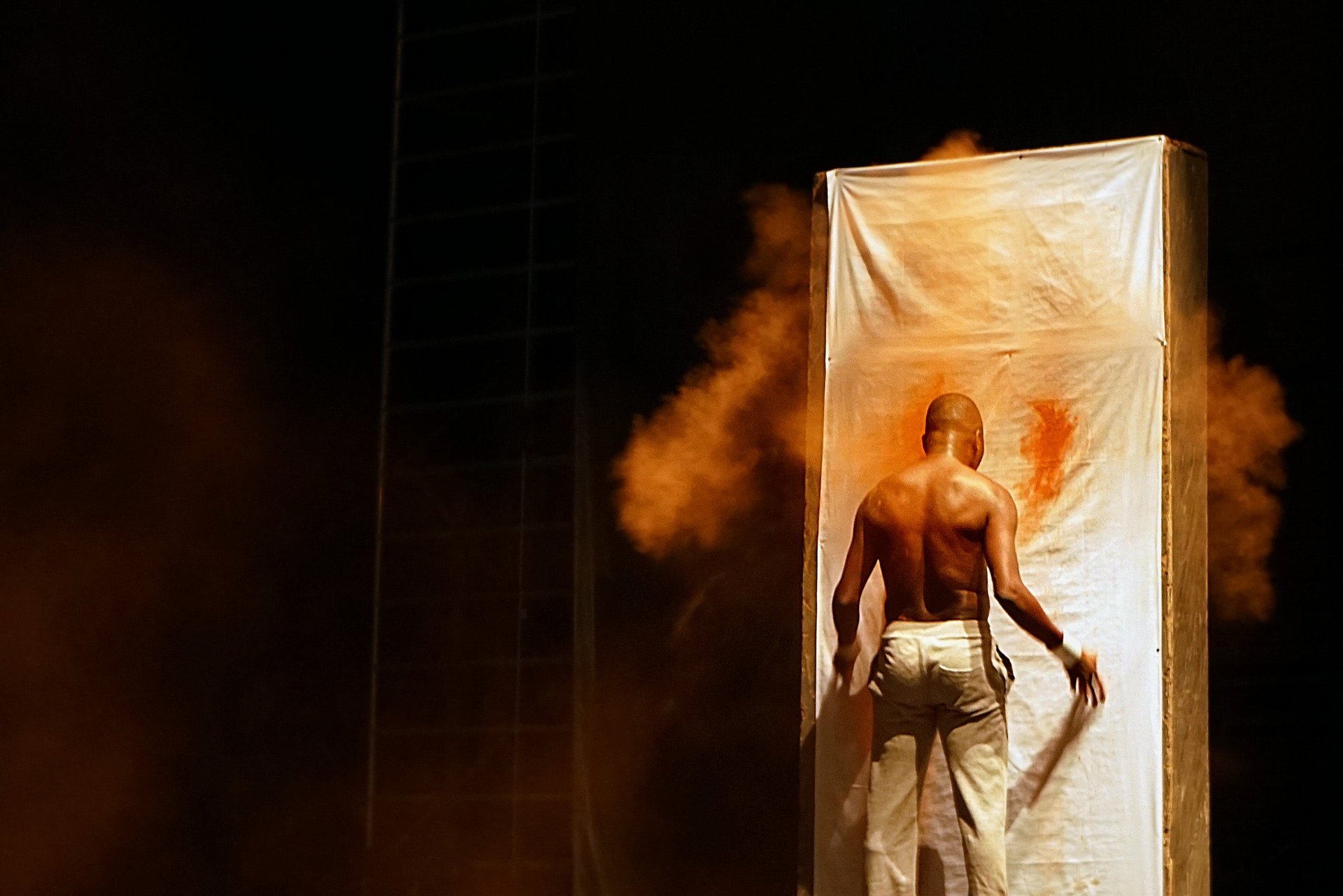

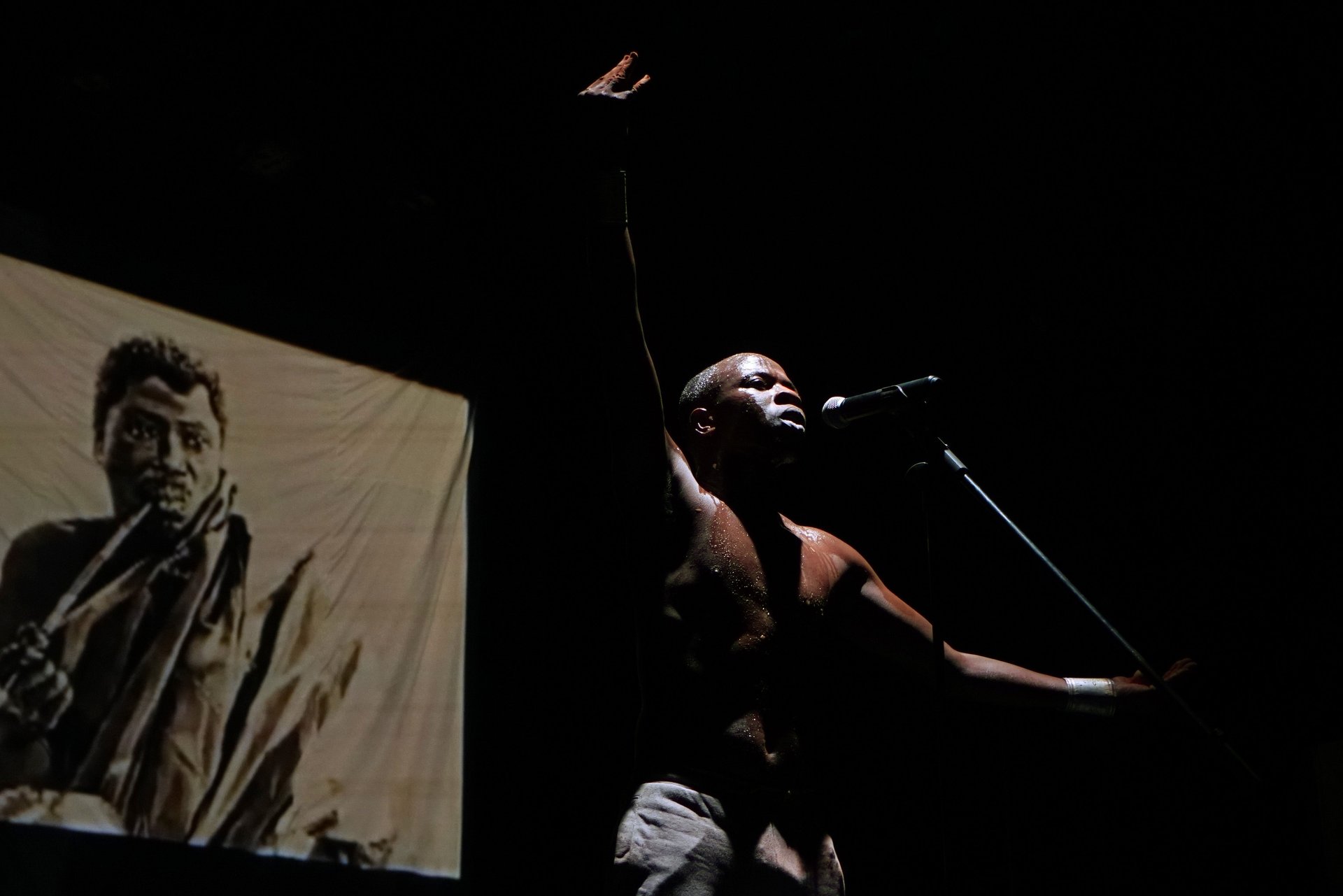

During one performance two female dancers threw old shoes around the stage and grimaced in agony. Later, another performer blew red earth into the air and rubbed raw eggs over his face and bare chest, as he performed a piece about the Dahomey king’s resistance to French colonial rule, in the country now known as Benin.

Traditional troupes dressed in African cloth and cowrie beads, concluded the shows each night – a reiteration of Tassembédo’s belief that traditional dance should inform African experiments in modern dance.

While the festival ends this weekend, Tassembédo, like many dancers, musicians and artists in the Sahel region, hopes the political establishment will recognize the role that artists could play in healing fractured nations that have been plagued by jihadist violence.

“They think that art is irrelevant, but we speak in a way that can touch everyone,” she said. “It’s us, the artists, who can reunite everyone.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox