The story of the pharma giant and the African yam

It was a drug produced in Nottingham in the United Kingdom that led us on a journey to South Africa to visit muthi markets, archives, herbariums and nature reserves.

It was a drug produced in Nottingham in the United Kingdom that led us on a journey to South Africa to visit muthi markets, archives, herbariums and nature reserves.

We spoke with traders, healers, scholars and conservationists to learn more about Dioscorea sylvatica.

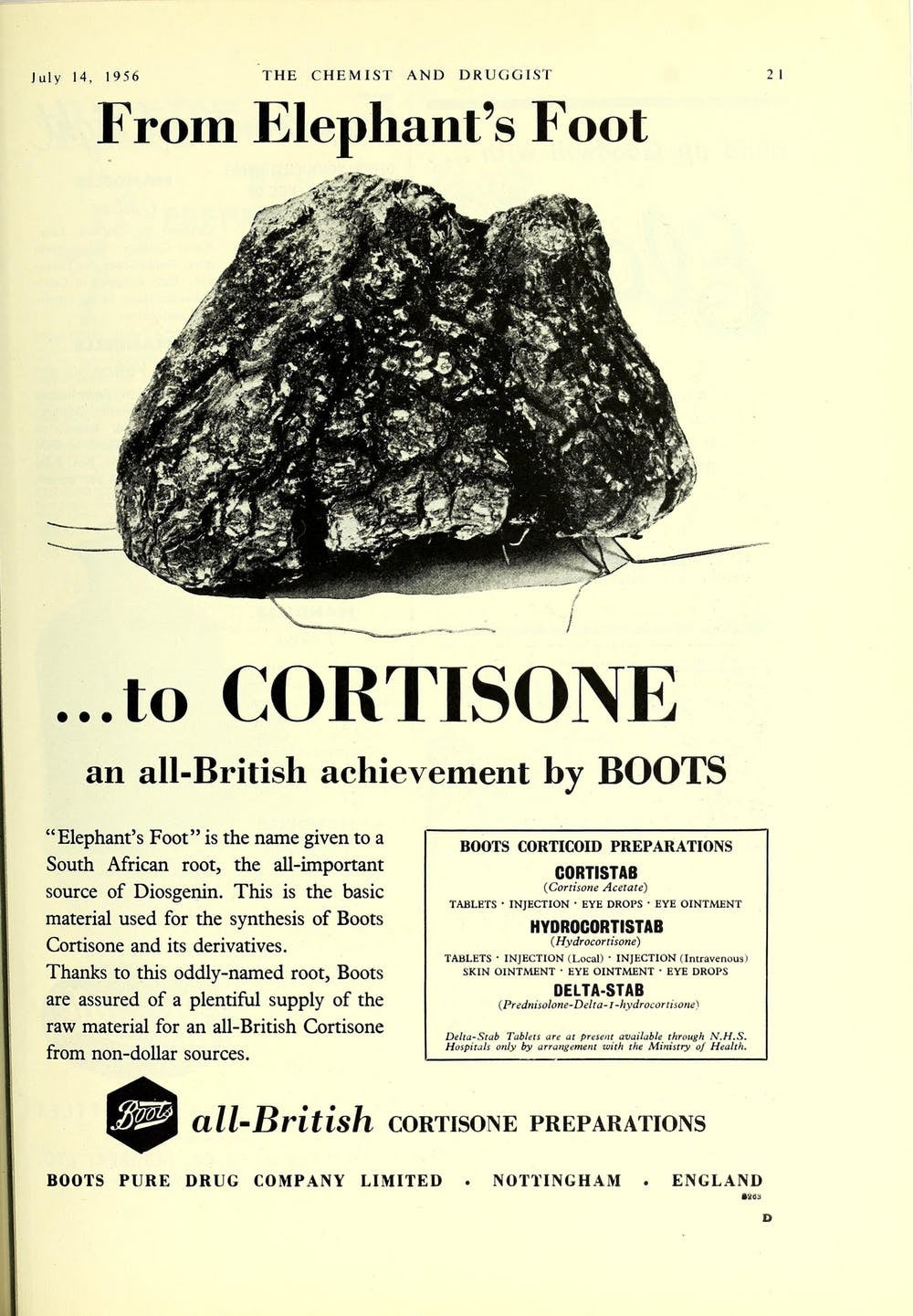

Dioscorea is a wild yam. Its name in different languages connects to its appearance—its rough skin resembles a tortoise shell. It’s known as ‘Elephant’s Foot’ in English, in isiZulu ‘ingwevu’, meaning grey/old or ‘ifudu’, meaning tortoise; in Sepedi the name is ‘Kgato’ – ‘to stamp’.

In the 1950s, the yam was heavily exploited by the British pharmaceutical firm Boots for the production of cortisone. But provincial conservation officials in South Africa fought back against the plundering of a wild plant that they recognised was in danger of being exploited to extinction.

A factory in Johannesburg

In 1949 scientists in the US announced the dramatic effects of a new drug, cortisone. It could be used to treat a variety of ailments, from arthritis to allergies to lupus and skin conditions. They found that cortisone could be made cheaply from diosgenin, extracted from Mexican wild yam species, and began a global search for supplementary plants.

By the early 1950s, South African botanists had identified Dioscorea sylvatica as promising. Boots, a major British pharmaceutical company, was keen to develop a source of diosgenin to manufacture corticosteroid medicines and started a factory in Johannesburg in 1955 for the initial stages of processing the plant.

Systematic extraction began in the eastern and north eastern part of the country, plundering a plant used by traditional healers for muthi (traditional medicine).

These actions weren’t a direct case of ‘biopiracy’ – in the sense of an obvious and deliberate theft of indigenous knowledge for profit. Nevertheless the exploitation of this plant took place against the backdrop of the history of plant collection and export from South Africa. Bioprospecting was facilitated by a longer process that involved drawing on a range of local knowledge in collection and scientific classification.

The conversations we had with South African traditional healers in muthi markets in Johannesburg and in Acornhoek, a rural area of Mpumalanga, brought up important questions on knowledge, ownership, plant exploitation, systems of thinking about disease and healing, and conservation.

Indigenous knowledge

The concept of medicine (muthi) is very different to the dominant pharmaceutical paradigm. Rather than a single drug to ‘cure’ a single disease, ill-health and treatment are understood in a more holistic way.

When we went to meet healers, we took along a piece of the yam bought from a muthi market in Johannesburg, as well as the 1950s Boots advert that had started us off on this research.

Most of the healers we met were familiar with the plant. Those who knew it described it as powerful with both topical and ritualistic uses for cleansing and protection.

The local knowledge that led to an interest in the plant from botanists and scientists is rarely recorded in any detail in archives. We were interested in how Boots in Nottingham came across a wild South African yam as a starting point for the manufacture of cortisone.

The UK connection

From our limited conversations with traditional healers and looking at botanical records, it is clear that medicinal yams were known and used across many different South African communities well before the steroid industry took an interest. However, interest in Dioscorea in the 1950s was triggered by US research on Mexican wild yams and a global search for similar plants.

A South African botanist recorded in the 1910s that the plant was used by African people for its saponins with medical properties. A wider range of uses were mentioned in The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern Africa, first published in 1932.

In a 1950s report on their collection for Boots’ South African collaborators Biochemico, there is a brief reference to local knowledge:

The actual digging was done by locals who need no more training than to be shown an “ingwevu” plant (which the vast majority in that area know in any case) and the size of the tuber required.

The digging referred to here is the extraction of about 6,000 tonnes of wild yams. This was only curtailed when the plant population became endangered and South African government conservationists stopped exploitation.

Natal Parks Boards officers were uneasy about mass exploitation of a wild plant and attempted to enforce strict conditions.

By 1960, they succeeded in terminating permits and Boots ceased production of South African diosgenin. This was a significant case for a fledgling provincial conservation authority. The protection of plants such as D. sylvatica attracted little public attention and it is not a well-known story, but this episode was important in developing institutions and strategies for plant protection and state conservation more generally.

Future protection

Healers in South Africa seem to be well aware of their position – carriers of traditional knowledge that could be lost, but also protectors of knowledge they fear will be exploited for profit with no benefit for them or their communities. Some have worked with campaigners and legal teams to test and record the efficacy of traditional plant medicines, and to prove existing knowledge, to gain recognition that could lead to greater government protection.

A landmark case in 2003 saw the South African San Council sign a benefit sharing agreement with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research for the use of Hoodia as an appetite suppressant and diet drug. The legal struggle led by the San Council was eventually successful and influenced subsequent legislation on indigenous knowledge and benefit sharing.

For the Elephant’s Foot yam it’s 70 years too late. But it has a lot of stories to tell.

Rebecca Beinart, an artist and researcher, accompanied the author – her father – and contributed to the research for this article.

This is the fifth article in a series on drug regimes in southern Africa. They are based on research done for a special edition for the South African Historical Journal. Read the full paper over here.

William Beinart, Professor, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.