Nigeria’s biggest battle with coronavirus will be beating misinformation

In the wake of Nigeria’s first coronavirus case, local authorities are preparing to face a test of public health systems and infrastructure.

In the wake of Nigeria’s first coronavirus case, local authorities are preparing to face a test of public health systems and infrastructure.

For now, authorities say the index patient, an Italian business traveler who arrived in Lagos from Milan on Feb. 25, is “clinically stable” and is being treated at a dedicated facility for infectious diseases. But in the coming days, as work intensifies to identify possible infections and contain the disease, the government will have another fight on its hands too: tackling misinformation.

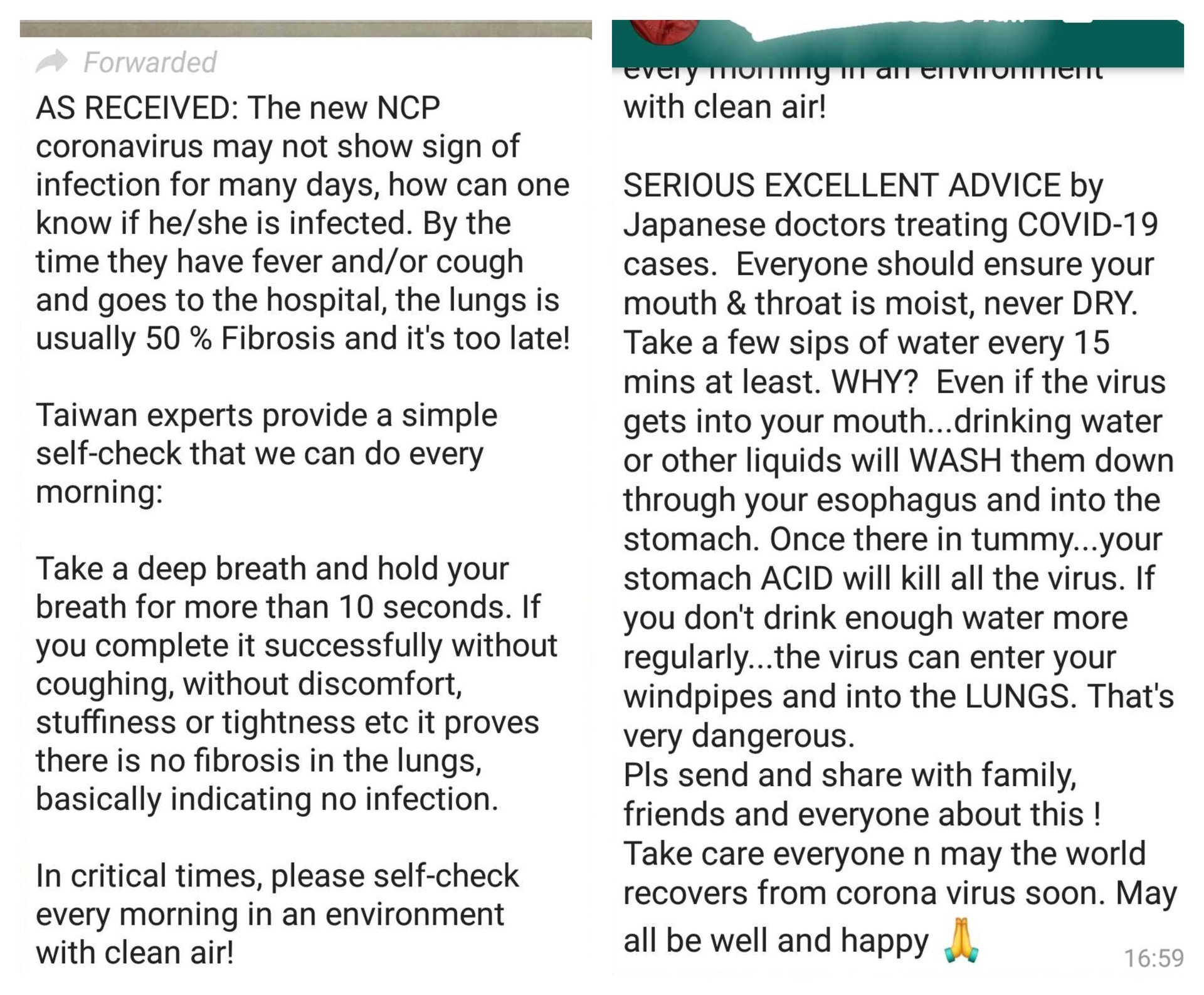

Indeed, as Quartz Africa was going to press, Whatsapp messages had started to spread with misleading information about the coronavirus.

With fears among locals likely to rapidly grow after the first confirmed case, it could result in the spread of inaccurate hearsay and panic-induced misinformation. There is already worrying precedent in very similar circumstances.

In 2014, while the devastating Ebola epidemic raged in parts of West Africa, a viral WhatsApp broadcast prescribed bathing with or drinking salt and hot water mixtures as a “cure” for the dreaded disease. Even though there was no medical basis for it, the “prescription” went viral enough for the government to have to officially debunk it. But that ultimately proved futile, as at least two people died and several others were hospitalized over excessive salt consumption.

False claims can even come from government sources too: in 2014, Nigeria’s former information minister claimed the government had acquired Ebola vaccines in preparation for an outbreak even though no vaccines existed at the time.

Given the increasingly global scale of infections with over 80,000 cases in nearly 50 countries, the possibility of similar bogus claims making the rounds and being adopted out of desperation is very real. To be clear, such misinformation episodes are not exclusive to Nigeria or even Africa, as anti-vaccination conspiracy theorists in the United States and Europe show. But the threat of more damaging after-effects are more pronounced here given traditionally weaker and under-equipped health systems

For its part, the Nigerian government has attempted to stay ahead of the narrative, publicizing its preparation plans even before its first confirmed case and sensitizing the public through official press releases and social media.

But social media platforms particularly represent a potent danger with regard to misinformation. “Misinformation spreads fastest on WhatsApp at times like this,” says Mayowa Tijani, a fact-checker with AFP. “The more trusted the source is, the more damage it is likely to cause,” he adds.

WhatsApp’s potential as a tool for misinformation is further amplified by its sheer popularity: it’s the most popular messaging app across several African countries, including Nigeria. Local telecoms operators have also created WhatsApp-only data bundles for users. While admitting to the magnitude of its “fake news” problem, WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, has seemed uncertain of how best to tackle it.

For its part, Facebook, also a widely popular social media app in Nigeria, has deployed a number of features to curb misinformation. Last August, its third party fact-checking program was expanded to include 11 African languages, including Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa, Nigeria’s three major languages.

Despite the best efforts of social media platforms, a bulk of responsibility of plugging information gaps currently lies with the government. “The government has to take out all opportunities for speculation by providing all possible information,” Tijani says. “The more people know, the less they speculate.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox