Côte d’Ivoire’s president rules out a third term, but it’s no guarantee elections won’t get messy

When Côte d’Ivoire’s President Alassane Ouattara announced on Mar. 5 he would not stand for a third term in presidential elections scheduled for Oct. 31, many Ivorians and democracy watchers around Africa breathed a collective sigh of relief.

When Côte d’Ivoire’s President Alassane Ouattara announced on Mar. 5 he would not stand for a third term in presidential elections scheduled for Oct. 31, many Ivorians and democracy watchers around Africa breathed a collective sigh of relief.

Ouattara’s mixed messages on whether he would seek re-election or not had created substantial uncertainty. In the months prior to his declaration, Ouattara repeatedly suggested the 2016 constitution allowed him to run again, a view disputed by the opposition and large sections of the country’s population.

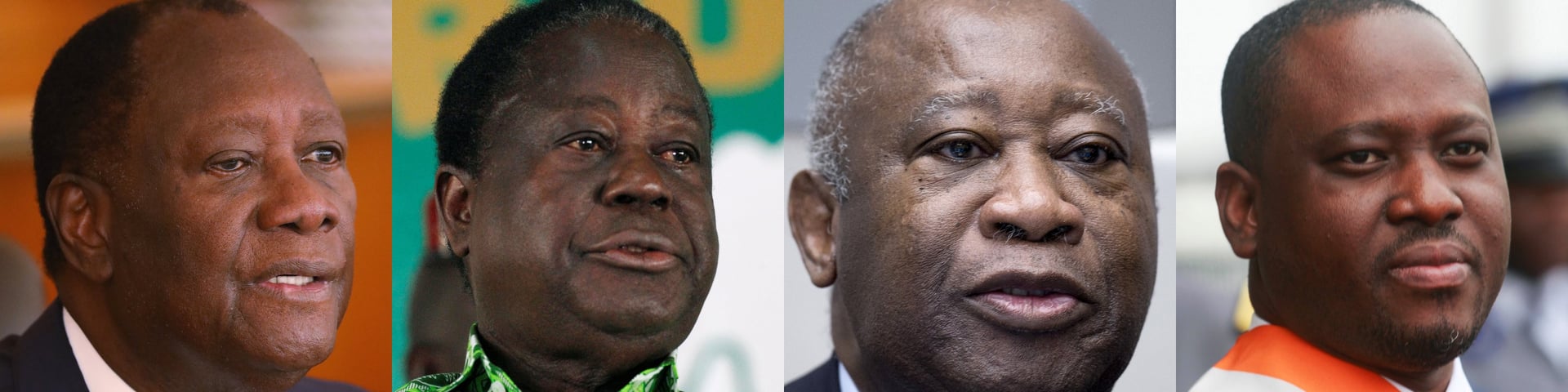

On Friday (Mar. 13), the ruling Rassemblement des Houphouëtistes Pour la Démocratie et la Paix (RHDP) announced it would field prime minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly, an Ouattara acolyte, as its candidate instead.

The ruling Rassemblement des Houphouëtistes Pour la Démocratie et la Paix (RHDP) is now widely expected to field prime minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly, an Ouattara acolyte, as its candidate.

But Ouattara’s withdrawal, if it is indeed a withdrawal, does not eliminate the uncertainty. The likely presidential bids of civil-war era heavyweights threaten a return of a destructive winner-takes-all mentality in politics the country thought it had overcome.

In his nearly ten years in office, Ouattara has overseen a remarkable political and economic turnaround. The former IMF economist came to power following a violent electoral crisis in 2010-11 that prompted France to intervene on his behalf. Ouattara inherited a country deeply divided by two civil wars over questions of national identity—in both of which he played a central role.

The extradition of Ouattara’s predecessor and civil war opponent Laurent Gbagbo to the International Criminal Court in 2011 paved the way for peace. Presidential elections in 2015, which saw Ouattara win re-election in a landslide, were widely deemed free and fair.

As stability returned, so did investors. Thanks to prudent economic policy and large-scale infrastructure investment, Côte d’Ivoire’s GDP growth rate has averaged nearly 8% since 2012. In 2017, it was Africa’s fastest-growing economy. For 2020, the IMF forecasts 7.3% growth.

These democratic and economic gains are now at risk. Over the past one and a half years, the broad-based alliance that has underpinned Côte d’Ivoire’s political stabilisation has begun to fracture.

In February 2019, Guillaume Soro, a former leader of the pro-Ouattara New Forces rebel group, resigned as president of the parliament, after refusing to support the RHDP bloc’s merger into a unified party under Ouattara’s leadership. Months earlier, ex-president Henri Konan Bédié, a one-time rival of Ouattara’s who later became his close ally, walked out of the coalition.

Soro has officially declared his intention to challenge the RHDP in October. Bédié is expected to follow suit. Although neither candidate is likely to muster an outright majority, both have significant followings.

In December, government authorities issued an arrest warrant against Soro over charges of fraud and plotting an “attempt against the state authority”. Soro claims the allegations are politically motivated. The timing of the warrant, which has prevented Soro from returning to Côte d’Ivoire after a six-month absence, suggests the RHDP takes Soro’s challenge seriously. When word spread that his flight had to be diverted because of the warrant, pro-Soro protests erupted in Abidjan.

Laurent Gbagbo’s potential return further complicates the situation. In January 2019, the ICC cleared Gbagbo of all charges. He currently remains in Belgium pending an appeal against his acquittal but has made no secret of his political ambitions.

It is entirely unclear whether Gbagbo will be able to return to Côte d’Ivoire for the election and whether his party, the Front Populaire Ivorien, would pick him as its contestant. But a meeting with Bédié in Brussels last July has fuelled speculation of a pact that could see Gbagbo back Bédié’s presidential bid in return for another political office should their ticket win. An alliance of the former heavyweights would be certain to shake up the election and could pose a serious challenge to Coulibaly—provided the government does not sabotage their plans.

Although the risk of new armed conflict is low, a series of mutinies by former rebel soldiers in 2017 and pockets of violence during the 2018 local polls highlight a residual potential for instability. As candidates seek to strengthen their position ahead of October’s vote, there is a risk they could resuscitate inflammatory rhetoric and sow distrust in the country’s electoral authorities. A disputed election could deal a severe blow to Côte d’Ivoire’s political and economic progress.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox