African countries don’t need donated ventilators without revamping their health systems first

As Covid-19 has spread across the globe, a worldwide shortage of ventilators has left hospitals scrambling to care for the sick. Nowhere is the shortage expected to be more acutely felt than in Africa, where many countries have only a handful, and some have none at all.

As Covid-19 has spread across the globe, a worldwide shortage of ventilators has left hospitals scrambling to care for the sick. Nowhere is the shortage expected to be more acutely felt than in Africa, where many countries have only a handful, and some have none at all.

An influx of ventilators may seem like the obvious solution, and organizations like the Jack Ma Foundation have generously stepped up in that regard. Unfortunately, I’ve learned firsthand why such an approach is insufficient.

In 2008, I co-founded an organization that sought to address the lack of access to clean water in several poor communities in Nigeria. Building water wells seemed like the best and quickest way to solve the problem, but a few months after building them, each one had broken down since the communities lacked the capacity or expertise to maintain them.

I later learned there are more than 50,000 broken wells in Africa alone, and in some communities as many as 80% of donated wells are broken. Through that experience, I learned a hard lesson: even when there seems to be an urgent need, simply providing resources without considering the local context is rarely the right approach.

For healthcare systems to effectively leverage ventilators in the fight against this coronavirus they require an immense amount of resources and expertise that many African countries lack. There’ll need to be constant electricity and a consistent supply of accompanying sedatives, intravenous medicines, and intravenous pumps for ventilators to add real value.

Healthcare professionals will need to be trained to use them, and a reliable system will need to be put into place for maintaining the expensive machines. This simply isn’t realistic for many healthcare systems on the continent, let alone an efficient use of limited resources. It’s clear that a different and more contextual solution is necessary for Africa to keep Covid-19 at bay.

What Africa needs

Africa needs solutions geared to the African context. Although that may sound trite and cliché, it’s important to note since the beginning of the global pandemic, many African countries have copied and pasted policies from wealthier economies with little regard for how those policies would work on the continent.

For instance, how is “sheltering in place” feasible in economies where a majority of people lack access to water and sanitation at home and must leave their homes in order to eat? Instead, African stakeholders must factor in countries’ strengths, existing infrastructure, and financial limitations. The depth of Africa’s poverty certainly complicates the continent’s response to the spread of COVID-19, but it doesn’t render it impossible.

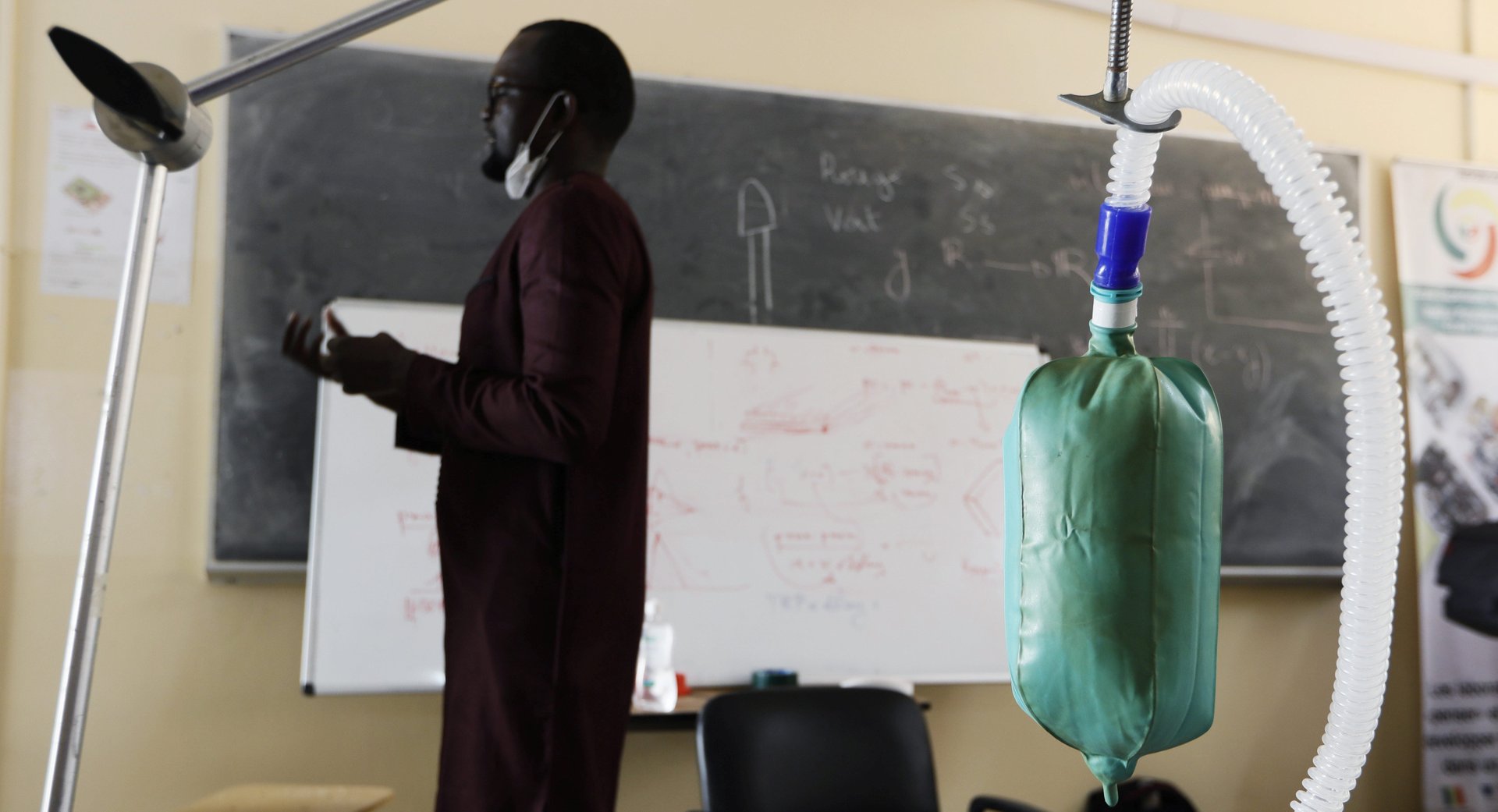

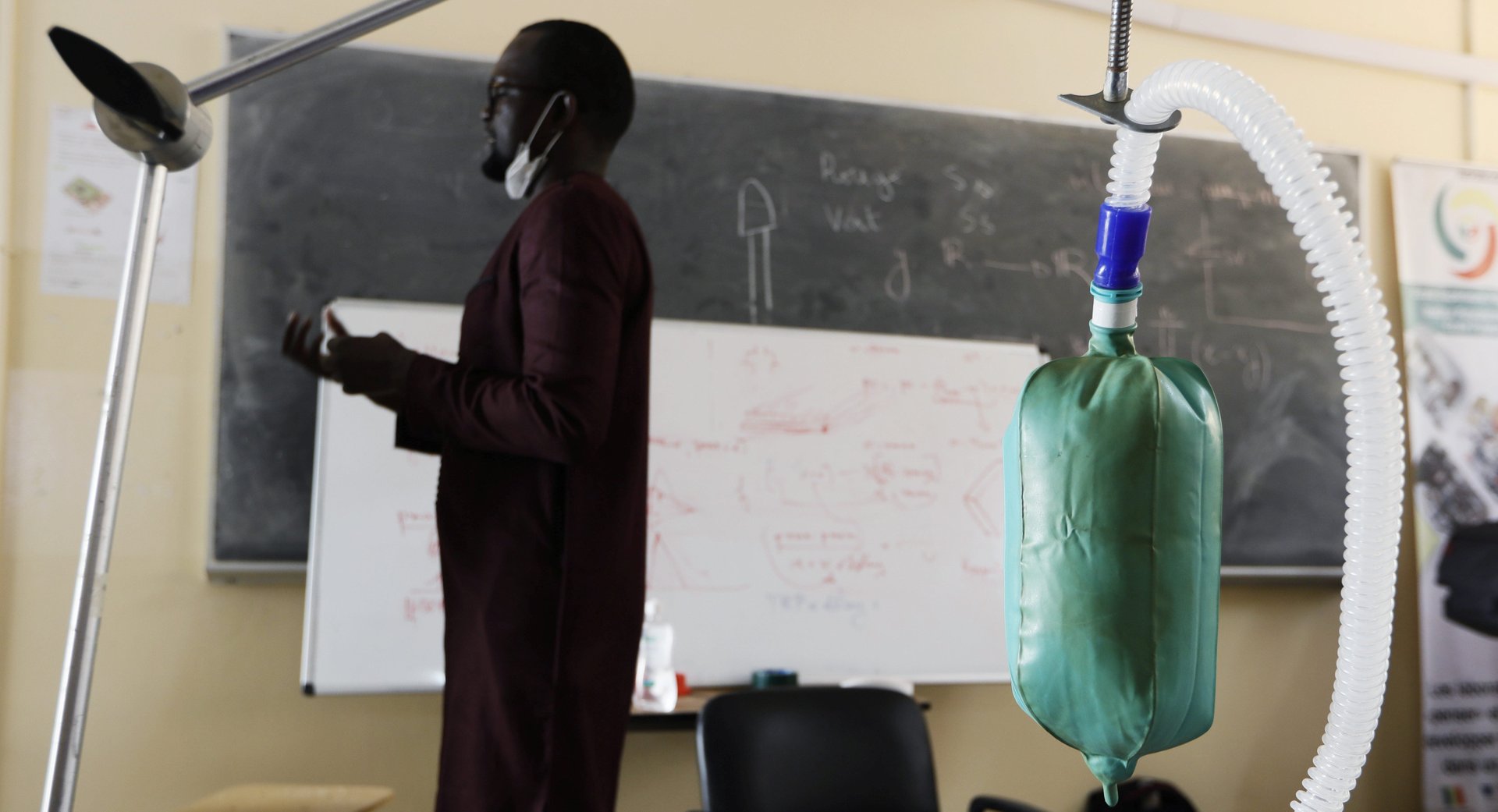

In Senegal, for instance, innovators are developing interventions that the country’s healthcare system has the capacity to absorb and sustain, including a $60 ventilator produced by 3D machines. In contrast with donated ventilators that cost as much as $16,000 and require an entire infrastructure for use, the $60 ventilator doesn’t have as many features and requires less energy and medical training. Another example is a simple, $1 Covid-19 testing kit that can be administered in communities that lack sophisticated healthcare centers. As Senegalese scientist Amadou Sall explained, “there is no need for a highly equipped lab. It is a simple test that can be done anywhere.”

The knee jerk reaction to provide ventilators for Africa is understandable. It was the same reaction I had when I walked into poor communities that lacked water. But piecemeal solutions like these rarely have the intended impact since they fail to consider the local context; with some luck the solutions may work for a little while, but without a broader system in place to support them, they’re inherently unsustainable. With that, the next time an epidemic hits, Africa is bound to need donations of whatever new medical equipment will be deemed necessary.

What if, instead of donating expensive and resource intensive ventilators to African countries, more resources were channeled to fund local, context-driven innovations like the ones in Senegal? These innovations will not only provide care for the sick and speed up testing, but they will also birth a new generation of African innovators who will be better equipped to develop African solutions for the next pandemic.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox