Ethiopia and Egypt are pushing each other to the brink in a battle for control on the river Nile

When Ethiopia, this week, criticized the Egyptian government for its “unprincipled” stand on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) it raised the stakes on one of the Africa’s most contentious diplomatic negotiations in recent decades.

When Ethiopia, this week, criticized the Egyptian government for its “unprincipled” stand on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) it raised the stakes on one of the Africa’s most contentious diplomatic negotiations in recent decades.

The comments came even though both states have expressed a willingness to return to tripartite talks with Sudan, over the dam. The key source of the tension with Egypt is that Ethiopia remains adamant to start filling the dam’s reservoir by July.

“Instead of earnest discussion, Egypt has used the negotiation platform to demand that the dam be smaller, carry a lower volume of water, and be turned into something that wouldn’t fulfill our needs,” said Gedu Andargachew, Ethiopia’s foreign minister speaking at a press conference with political party representatives at Addis Ababa’s African Union Conference Hall on Wednesday. “It’s up to them to leave this obstructive approach and instead cooperate with the parties involved.”

Ethiopia’s insistence on filling the reservoir without an agreement on technicalities is a major sticking point for Egypt. The dam’s reservoir has a capacity of 74 billion cubic meters, and Ethiopia plans on storing around 18.4 million cubic liters of water in it in the coming two years.

Egypt says doing so without a signed agreement is a breach of international law and would dangerously impact its own water supply downstream. Ethiopia has reiterated that it doesn’t need Egyptian approval to fill the dam. US officials, who Egypt had called in to help mediate, had insinuated that progress had been made, but the pair’s differences were many and eventually led to Ethiopia’s pulling out from a final round of scheduled roundtable talks in late February. Ethiopian officials accused the Trump administration of pressuring the Horn of Africa country to make unreasonable concessions.

“Ethiopia will never sign on an agreement that will surrender its right to us the Nile River,” Ethiopia’s ambassador to the US, Fitsum Arega wrote on Twitter at the time.

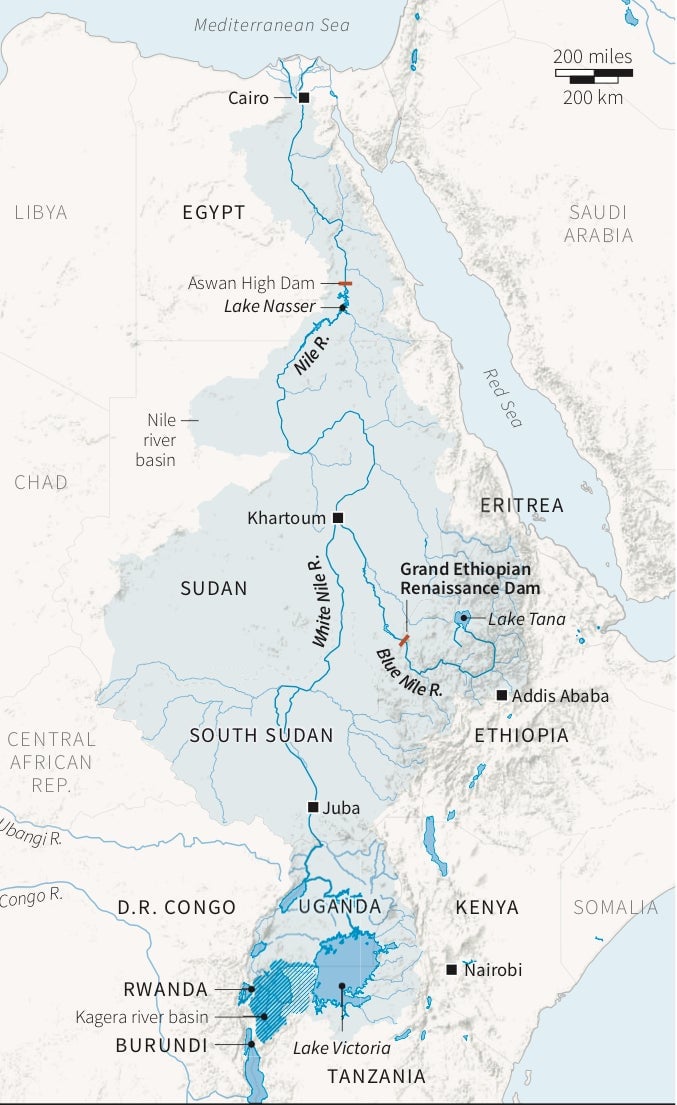

The diplomatic spat starts with Africa’s longest river, the Nile, which runs through 11 countries. Ethiopia contributes about 85% of the Nile water flowing to Sudan and Egypt. The 11 nations are hoping that the massive Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam will open up many new opportunities from electric power supply, agricultural irrigation to reducing evaporation losses.

When completed, the dam will have installed capacity to generate 6,000 MW electricity to relieve Ethiopia’s acute energy shortage and also export to Sudan and possibly Egypt. The dam’s 74 billion cubic meters of water is about half the volume of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt.

Tripartite effort

Months into the deadlock, Sudan has lobbied to reinitiate the stagnated tripartite effort and has gotten a positive response from Cairo and Addis Ababa, despite the open bickering between the two.

US mediation had been sought by Egyptian president Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, after Ethiopia’s prime minister Abiy Ahmed agreed to the involvement of a third-party mediator. From November to February, diplomats from Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan shuttled between Washington DC, Khartoum, Cairo and Addis Ababa. World Bank representatives were also brought in as additional arbitrators.

In November, Ethiopia agreed in principle to an Egyptian request that the dam filling process be carried out in stages over seven years. But the nitty gritty of how it would be carried out, including the speed with which the reservoir would be filled, left the two at odds.

In this regard, the US has done little to bring the opposing sides together, and Ethiopia eventually decided not to attend a final round of negotiations in late February, where the sides were supposed to sign a legal and binding agreement. Ethiopia rejected terms of a deal it deemed favorable for Egypt, which led to accusations by Ethiopians that the US was trying to coerce Ethiopia into compromising on its dam aspirations. Ethiopians in the US took to the streets to protest “US pressuring of Ethiopia.”

Egypt meanwhile, took issue with Ethiopia’s absence from the final round of talks, and of its refusal to sign the agreement which had actually been drafted by US and World Bank mediators. In a letter penned to the United Nations Security Council earlier this month, Egypt’s foreign minister Sameh Shoukry decried Ethiopia’s “unilateralism, its lack of willingness to cooperate and its desire to fill the GERD regardless of the impact on downstream riparians.”

While the text of the treaty that American mediators hashed out isn’t publicly available, Shoukry gave a briefing of what it entailed in his letter to the UNSC. Among the clauses Ethiopia found unacceptable according to Shoukry, a compromise which included “mitigations measures,” which would be implemented even beyond the first stage filling period, if Egypt were to experience drought.

Ethiopia brands this as nefarious. “On the Egyptian side, negotiations until now were hindered by Egypt’s desire to maintain its historical hegemony,” said Dr. Seleshi Bekele, Ethiopia’s minister of Water, Irrigation and Energy. According to the minister, dam construction progress currently stands at 73.7%

Sudan has shown a determination to de-escalate tensions, with prime minister Abdullah Hamdok believed to have arranged the continuation of tripartite talks by communicating with his Ethiopian and Egyptian counterparts in recent weeks. China has also lobbied the two to put and end to the spat and work towards peaceful resolution. Beijing’s interest likely stems from its financial support for the GERD project. Two Chinese state companies were awarded $150 million in GERD construction contracts last year.

But with Ethiopia’s Abiy telling Ethiopians that “not even the coronavirus” would hamper dam plans, and Egypt’s heavy-worded message to the UNSC, it would seem the impasse could be on the brink of deteriorating even further, come July.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox