Chinese trawlers with an illegal fishing record have been licensed by Senegal

Senegal’s fisheries ministry has issued fishing licenses to vessels of a Chinese industrial fleet involved in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activity in recent years, according to a new investigation by the environmental group, Greenpeace.

Senegal’s fisheries ministry has issued fishing licenses to vessels of a Chinese industrial fleet involved in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activity in recent years, according to a new investigation by the environmental group, Greenpeace.

The report, Seasick: As Covid-19 locks down West Africa, its waters remain open to plunder, is based on the activist NGO’s observations of fishing vessels and fish meal and fish oil factories in Senegal, Gambia and Mauritania between March and July.

It digs into the events surrounding the unprecedented 52 foreign vessels that applied for fishing licenses from the Senegalese government earlier this year, amid lockdown restrictions owing to the coronavirus. The applications infuriated several Senegalese fisheries stakeholders, including artisanal fishermen, industrial shipowners and civil society organizations.

Never before had so many foreign vessels applied for licenses, especially with the lockdown constraints and food insecurity. Civil society groups like, APRAPAM, argued that granting the licenses would amplify the fishing pressure on Senegal’s waters, threaten sustainability and the livelihoods of artisanal fishing communities already suffering from the restrictions in place to combat the pandemic.

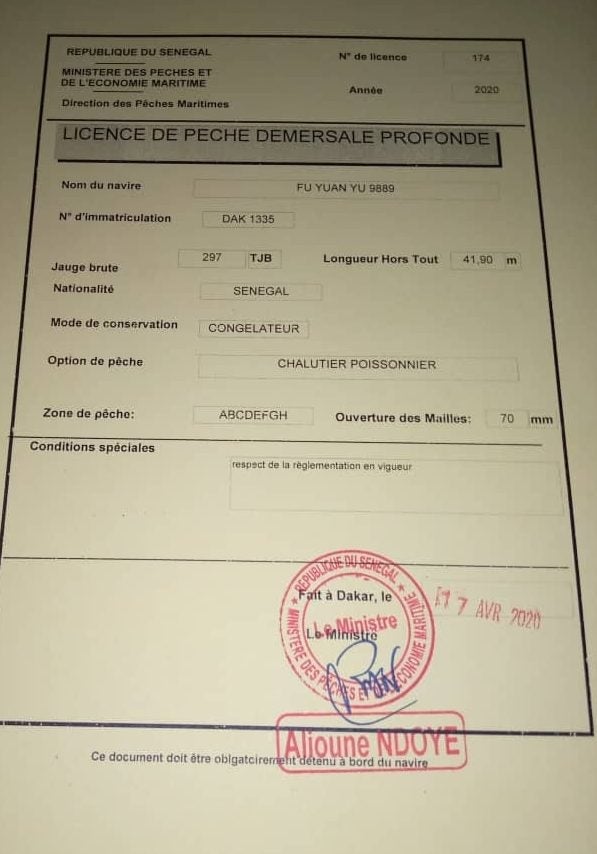

The uproar forced the fisheries ministry in June to publicly announce its rejection of the 52 applications. But local media reports uncovered evidence showing that the government secretly issued a license to the Chinese vessel, Fu Yuan Yu 9889 on April 17. And the vessel’s operator, Univers Peche, went on to seek licenses for an additional nine vessels. Greenpeace also confirmed local media reports showing two of those vessels from the Fu Yuan Yu fleet, Fu Yuan Yu 9885 and Fu Yuan Yu 9888, received licenses. For local fisheries stakeholders, these licenses have also exposed Senegal’s opaque licensing process.

“If the license process was transparent, no one would be asking whether the department had signed new licenses or not,” says Mor Mbengue, an activist and member of Platform of Artisanal Players of Senegal’s Fisheries. And what’s more, “the artisanal fishing actors, who are the most impacted, are not always consulted by authorities when licenses are attributed even though they should be as representatives of the Committee of License Attribution.”

In 2017, the Fu Yuan Yu fleet was reported fishing illegally in protected areas in Djibouti.

Up to 90% of Senegal’s fisheries are fully fished or facing collapse, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. This overfishing has led to a food crisis, which has been exacerbated by Asian and European fleets prowling the seas off West Africa. Recently, revenues from the artisanal sector have been hit by the closure of markets to curb coronavirus.

“Unlike most other businesses, including the artisanal fishing activities, the multinational industrial fishing sector has in several cases continued operating without being restricted by the Covid-19 lock-down,” says Tal Harris, communications coordinator for Greenpeace Africa. “The already problematic competition between the artisanal sector and large-scale foreign fishing industries is thus made even worse for the declining West African fish stocks.

“Some of these foreign companies have even made attempts to profit from the Covid-19 lockdown to continue their illegal practices, knowing that the attention of civil society and the majority of actors is being captured by the pandemic,” says Harris.

At the moment, and because neither the African Union nor countries along the West African coast keep detailed records, an unknown number of foreign vessels are emptying West Africa’s waters, according to Greenpeace. It says to remedy this, regional and sub-regional list of vessels authorized to fish in the area need to be maintained as well as reliable data on stock status and transparency on issuing licenses to foreign vessels.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation in your inbox