Scientists have found new fossil tracks belonging to human ancestors in South Africa

Around a hundred thousand years ago, South Africa’s Cape south coast was a busy place. Giraffes, crocodiles, hatchling sea turtles, and large bird species populated the landscape. Early humans were there, too.

Around a hundred thousand years ago, South Africa’s Cape south coast was a busy place. Giraffes, crocodiles, hatchling sea turtles, and large bird species populated the landscape. Early humans were there, too.

We know all of this because of fossil track sites that today dot the Cape south coast, which is about 400 kilometers east of Cape Town. These sites date to between 400,000 years and 35,000 years ago, to a geological epoch known as the Pleistocene. The tracks were made on dunes and beaches, which became cemented over time. These ancient surfaces, which often preserve the tracks in remarkable detail, are now amenable to our inspection and interpretation. Our research team has been documenting these track sites since 2007.

A substantial body of archaeological evidence has accumulated, indicating that ancient humans on this coastline adorned themselves with jewelry, developed sophisticated tool technology, created some of the world’s first engravings and drawings, and harvested shellfish, and seafood in a co-ordinated manner. In short, they exhibited many forms of modern human behavior—and the region has been described as a refugium in which our ancestors survived tough climatic conditions, and then thrived.

Our team found its first hominin track site in 2016. We identified 40 tracks, estimated to be around 90,000 years old and indicating a party of humans traveling fast down a dune slope. The tracks were in a small cave west of what’s now the town of Knysna.

Now we’ve found three further hominin track sites—and possibly a fourth. The sites are described in a recently published article in the South African Journal of Science. One site, containing 32 tracks in a number of trackways, was unusual in that it we could examine both the surface on which the tracks were made (on a fallen slab near the high water mark) and, under an overhang in the cliffs above, the surface containing the infill layer. In fact, the tracks showed better preservation on the latter surface.

These discoveries bring the total of southern African hominin track sites to six, following earlier discoveries at Nahoon Point in the Eastern Cape in 1965 and at Langebaan on the West Coast in 1995. Coincidentally, in the same week that our article was published, a site with tracks from approximately the same time period, and also attributed to Homo sapiens, was reported from the Arabian peninsula.

Our findings provide an addition to the global hominin fossil record. The more scientists know about where human ancestors roamed, and how they behaved, the better they can understand how and where humans developed, the threats they faced and how they overcame these.

What the tracks reveal

The three sites we have definitively identified lie within protected areas. One is within the Garden Route National Park, and two within the Goukamma Nature Reserve. This is good news because collaboration with the relevant authorities can lead to enhanced site protection and preservation.

Two of the sites described in our new research paper contained tracks of various sizes, suggesting the possibility of family groups. A third site contained three forefoot impressions with convincing evidence of toe impressions. Alongside these we found an array of nearly-parallel groove features and small circular depressions. These may have been made in the sand by a human using a finger or a stick.

At the fourth site we found tracks of the right size and the right pace length to suggest a human trackmaker. But they were only visible in cross section in cliff layers. We felt it prudent not to over-interpret these features and make a definite conclusion, although they were highly suggestive and occurred close to our 2016 hominin tracksite.

Fleeting sites

Anything that’s preserved in sand and stone is vulnerable once it’s re-exposed. Once these fossil tracksites are revealed by time and the elements, they may become rapidly eroded or even collapse into the sea. For instance, part of the ceiling of the hominin tracksite we discovered in 2016 has recently collapsed, and some of the tracks have therefore disappeared.

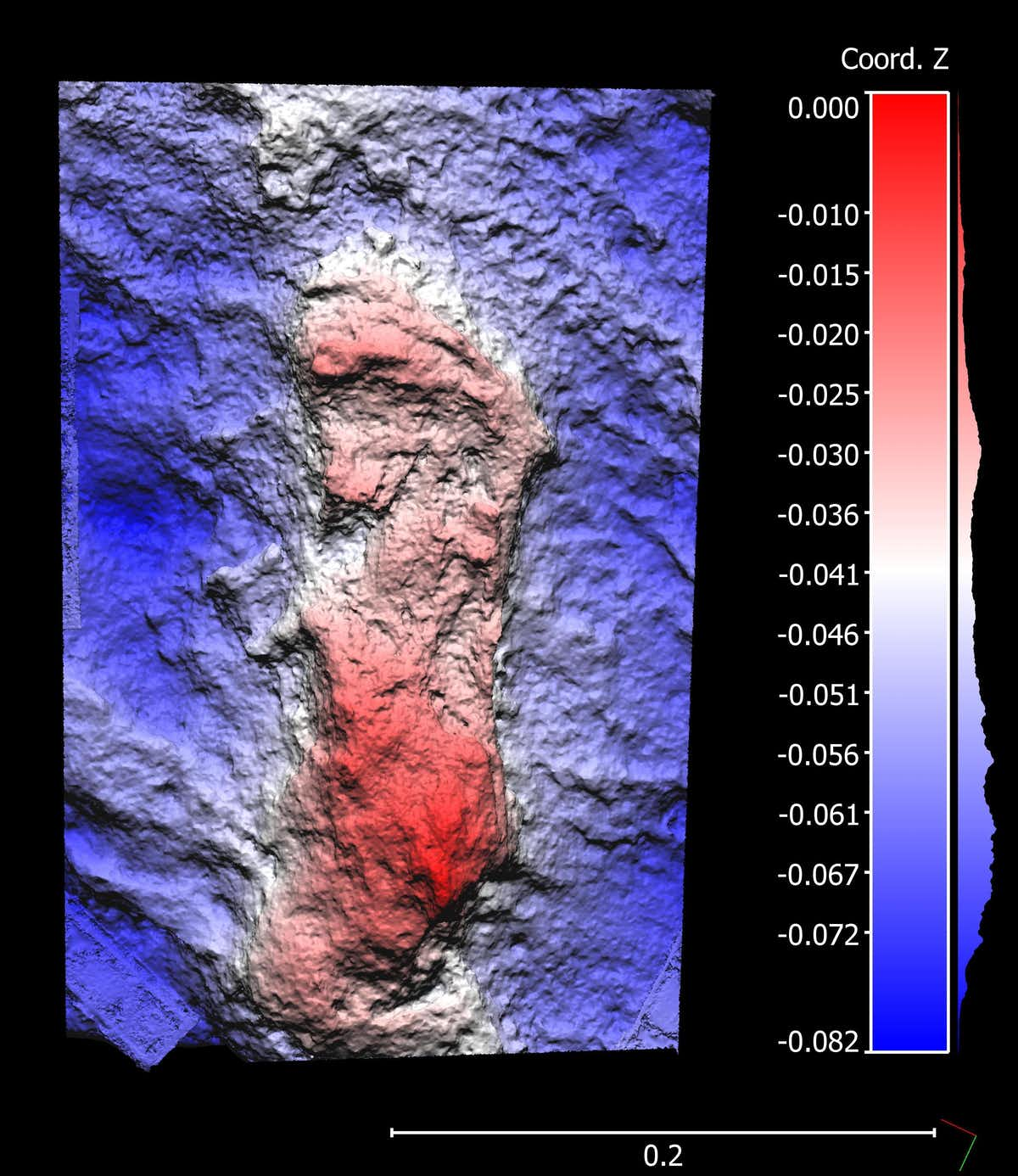

Luckily we were able to create a digital record of this site, taking more than a thousand photographs for photogrammetry, and thus generating a 3D model. This means the unique surface hasn’t been lost to science—and it will be possible to create an exact replica of it.

For now, we continue exploring and searching for new sites, knowing that we often enjoy just a short window in which to identify, research, and document them before they are lost during storm surges.

Charles Helm, Research Associate, African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, Nelson Mandela University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.