How online scammers fooled one of Africa’s biggest fintech startups

James Uche remembers how he frantically fought against a deadline to submit an English proficiency certificate to secure a scholarship for an undergraduate biotech degree at McMaster University in Canada.

James Uche remembers how he frantically fought against a deadline to submit an English proficiency certificate to secure a scholarship for an undergraduate biotech degree at McMaster University in Canada.

His full ride to McMaster was being sponsored by the St. Michael Foundation. When it offered him its international scholarship in mid-January, the foundation gave him two options to meet the English requirement. He could take the International English Language Testing System, or IELTS, a common standardized test for non-native English speakers, or an alternative recommended by St. Michael. Called the Online International English Proficiency Examination (OIEPE), it was touted in its website as the world’s premier English language test for international study, work, and immigration, accepted by more than 11,000 universities in over 150 countries.

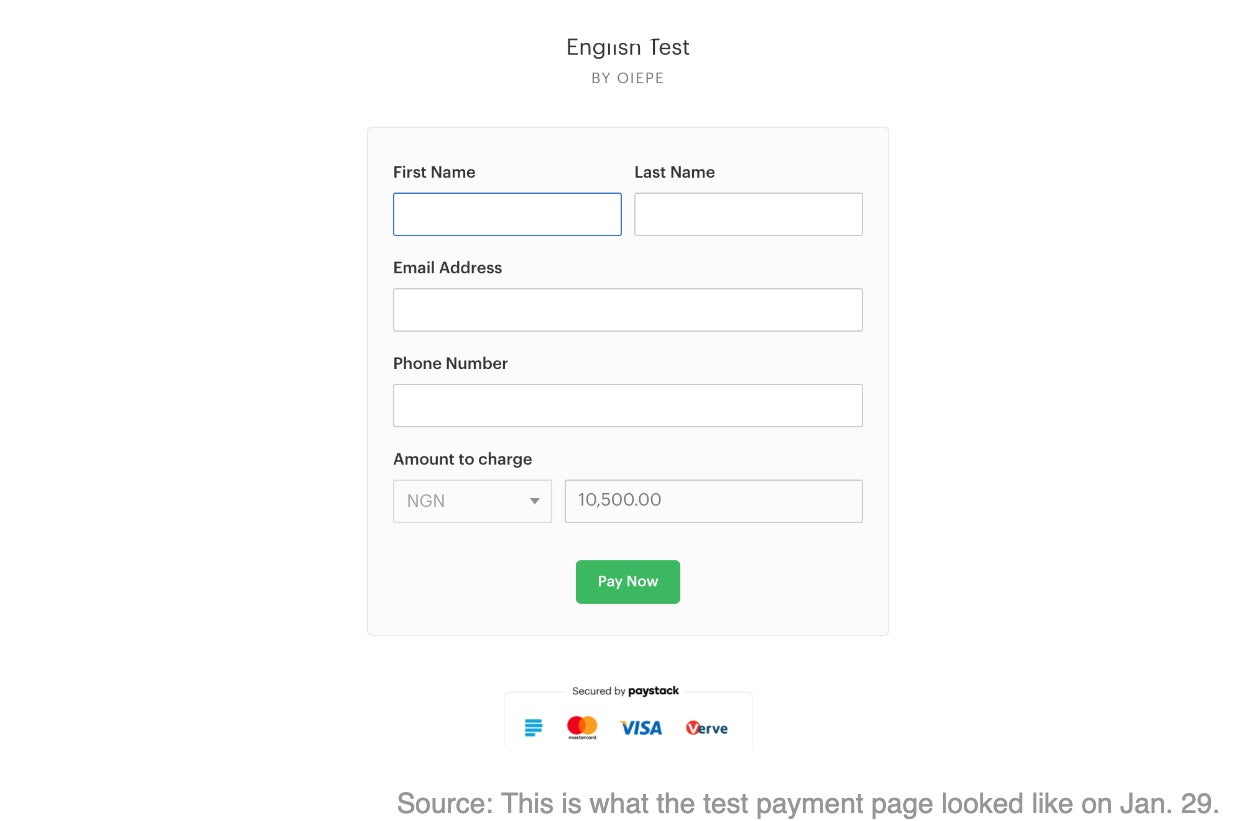

All Uche needed was to follow a link provided by the foundation to create a profile and pay the sum of 10,500 naira (about $25) via digital payments startup Paystack to generate the test access pin. The first two times he tried, the pin expired shortly after he got it. Anxious of losing his scholarship, he used another email to create a new profile and his mother’s debit card to pay again, altogether spending $75. Each time, he got a receipt from Paystack.

Uche succeeded on his third attempt. The test took him less than an hour and he scored 57%, far above the 40% required for his scholarship. He received his English proficiency certificate by email a few hours later, signed by both OIEPE’s president director and general manager. He went to a café, where he uploaded his resume and the certificate to a dedicated site, beating the deadline by two days.

Then he waited for his admission letter from McMaster, which the foundation promised would come in the next 30 working days. But the English test was the culmination of an elaborate scam to collect money from young Africans seeking to study abroad.

“I don’t know that someone born of a woman, created by God, can actually formulate such a thing to scam people,” says the 21-year-old Uche from his family home in Abia State in southeastern Nigeria. “I’m heartbroken,” he says. “My money is gone.”

A Youtuber with an enthusiasm for science, Uche graduated from Covenant High School in Abia, where he was a senior prefect, a top student leader normally appointed by the school teachers. He says he had been seeking university admission, but Nigerian public universities were on strike during most of last year, coupled with the coronavirus pandemic lockdown that kept even private school students at home.

On the surface, the scam looks like the old tricks that have been used for years to defraud hapless prospective students with fake scholarships. But it reveals a troubling new trend: The same impunity and loopholes that fraudsters normally use are now superpowered by fintech, making the potential windfall for the scammers and losses for the scammed even bigger.

The number of people who fell for the scam isn’t known yet. Paystack has refused to disclose the identity of the scammers and wouldn’t say the amount of money it raised for them.

“When we became aware of this merchant’s questionable activity, we deactivated their account immediately and are working with their bank to investigate this incident,” Paystack said in an email.

The broken fintech chain

According to Paystack, for merchants to get activated on its platform, they need to submit a number of “know your customer” documents that are reviewed before the business is cleared to accept payments. “Businesses in regulated industries are required to produce documents unique to their sector, such as certificates and licenses,” the company says.

In Nigeria, for example, Paystack requires prospective customers to submit the bank verification number (BVN) of any director or trustee, the certificate of registration from the Corporate Affairs Commission, the Nigerian agency responsible for the registration of for-profit and nonprofit organizations, and a corporate bank account. Similar requirements also apply to Ghana and South Africa where the company has extended its service.

It’s not entirely clear whether Paystack failed to properly vet the scammers, or whether current rules are not stringent enough to detect dubious customers.

For the scammers to have succeeded, at least one other corporate organization along the payments chain didn’t do its due diligence, says Babatunde Obrimah, chief operating officer, Fintech Association of Nigeria, a nonprofit organization that advocates for fintech in the country. The scammers only used Paystack as payment gateway on their website; the money they made had to be channeled into a bank or other financial institution. “Somebody at the end of the transaction is liable,” he adds.

Payment companies like Paystack are regulated by the Central Bank of Nigeria, which mandates that payment service providers ensure that all transactions on their platforms are validated by credible financial institutions. The central bank has launched an investigation into the scam and will provide further information after it is concluded, spokesman Osita Nwanisobi said in a text message.

Fertile field for fintechs and scammers

Nigeria, with about 200 million people and Africa’s largest economy, is a viable market for fintech startups. Between January and August last year, the value of e-payment transactions in Nigeria was 804 trillion naira (about $2 trillion) with online transfers accounting for nearly one-third, according to the Central Bank of Nigeria.

Paystack, founded by Ezra Olubi and Shola Akinlade in Lagos in 2015, was acquired by Stripe for about $200 million in October last year and now has more than 60,000 customers. Stripe didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Another Nigerian payment startup, Flutterwave, raised $170 million in a Series C funding round in March, projecting the company to about $1 billion valuation.

But as the payment platforms grow in the country, yahoo boys, a Nigerian moniker for internet fraudsters, are finding ways to cash in.

Young Nigerians are a particularly easy target for scholarship scams. Faced with rising unemployment, many are seeking to immigrate to high-income countries in hopes of a better life. Common tips to avoid falling prey to this type of scam include never paying a fee to apply, never disclosing sensitive personal information, and never responding to an unsolicited offer.

“When an opportunity feels too good to be true, it often is,” says Grace Ihejiamaizu who runs Opportunity Desk, a website that curates global educational and career opportunities. “Trust your instincts and take a step back to analyze the opportunity. Possibly invite a second eye that will be more rational, knowledgeable, and less excited about the opportunity, to give you valuable feedback.”

A new kind of scholarship scam

The scam Uche and others fell for didn’t rely on the usual tricks. Instead, the scammers designed an audacious scheme that involved many layers that unfolded gradually over months.

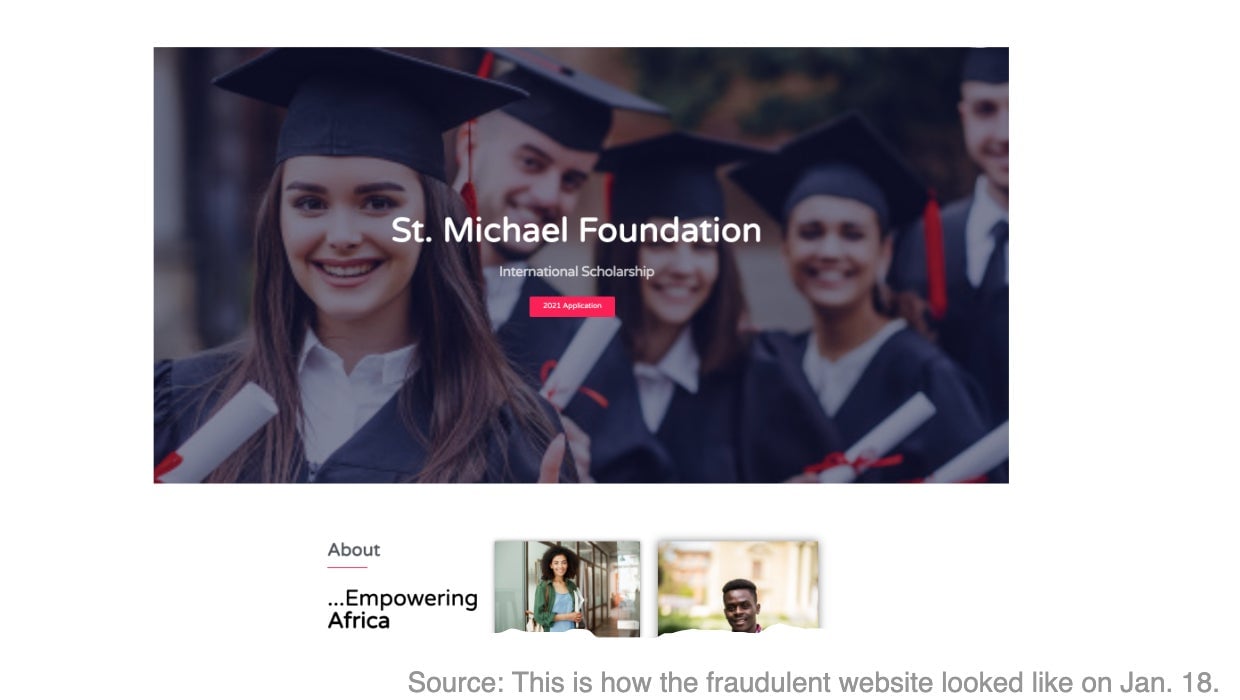

The scholarship application website had pictures of smiling students in commencement gowns, clutching books, and engaging in other activities on campus. The scholarship was meant for Africans for undergraduate and master’s degrees at one of nine universities in Australia, Canada, and England. The application only required two motivation essays without a specified word limit.

The fraudulent foundation opened up its application process in December, with a Jan. 11 deadline. Shortly after, applicants began to receive congratulatory messages for getting the scholarship. They were instructed to upload their resume and English proficiency certificate to a web link in order to secure their admission at the partner universities.

“I feel very weak now,” says 27-year-old Francis Ogiri, who was still expecting his admission letter when he learned from Quartz Africa that he had been scammed. He applied for civil engineering at the University of Tasmania in Australia and paid twice for the English test because the first access pin expired. He also paid another 2,500 naira for a sample English test to prepare. Ogiri has a diploma from the Nigerian Army Institute of Technology in Makurdi, Benue State, and has been living with his older sister and younger brother in Abuja, where he works as an office assistant.

The link to the scholarship appears to have been mainly circulated on WhatsApp and Facebook groups, where young Africans congregate to share scholarship opportunities; only one obscure Nigerian website, Explorer Arena, posted about the scholarship. Ogiri says he first learned about the scholarship through a link a friend sent him via WhatsApp, and became convinced that it was real after he searched it on Google. Another applicant, 28-year-old Aminu Adamu, who lives in Kano, says he too received the link through WhatsApp, and also fell for it after googling it. Adamu chose business administration at Monash University in Australia.

It’s easy to see why the applicants might have initially been fooled. When they searched the foundation, the top results were likely St. Michael’s College and St. Michael Foundation, both genuine organizations that have no connection to the fake St. Michael Foundation.

And, on cursory look, the scammers’ website appeared genuine. It plagiarized the text from another real organization, Mastercard Foundation, to explain what the scholarship was all about. The scammers also lifted the profile pictures of four board members from the Mastercard Foundation’s website, and passed them along as their own.

On Jan. 19, the Mastercard Foundation issued a disclaimer saying the fraudulent website used the foundation’s content and images to promote the fake scholarship. The website had been taken down the previous day, but by this time, the scammers had already sent congratulatory messages to the applicants and moved on with recommending the fake English test.

Still, all along there were clues of the scam. The domain for the test website was only registered in December, but falsely claimed that its copyright was from 2010. It had pictures and testimonies of students who had failed TOEFL and IELTS tests several times until they took the OIEPE, but the exam itself consisted of 30 poorly written questions to be completed in 45 minutes.

There were other red flags. Neither of the websites had social media accounts. And the US address of the foundation didn’t exist. But conducting basic online verification might not be within reach for the applicants who were motivated by the prospect of studying abroad.

For Chukwuebuka Amazu, who chose master’s in philosophy at the University of Ottawa in Canada, the scammers played a fast game on them, not only collecting their money but making them study for a fake English test. It’s a sobering reminder that the rapid spread of fintech in Africa doesn’t come without risk.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation in your inbox.