Why Africa doesn’t have its own Covid-19 vaccine

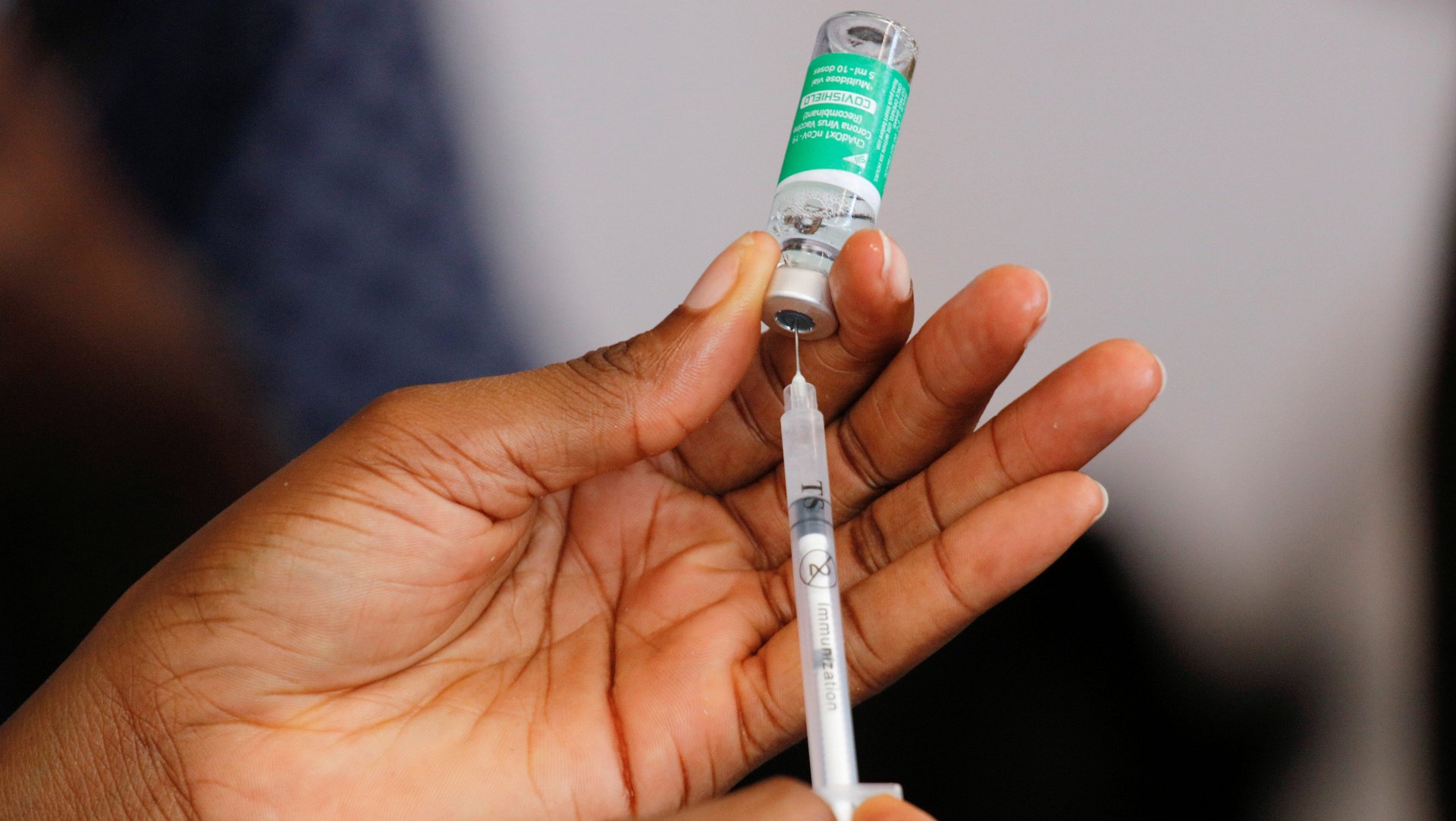

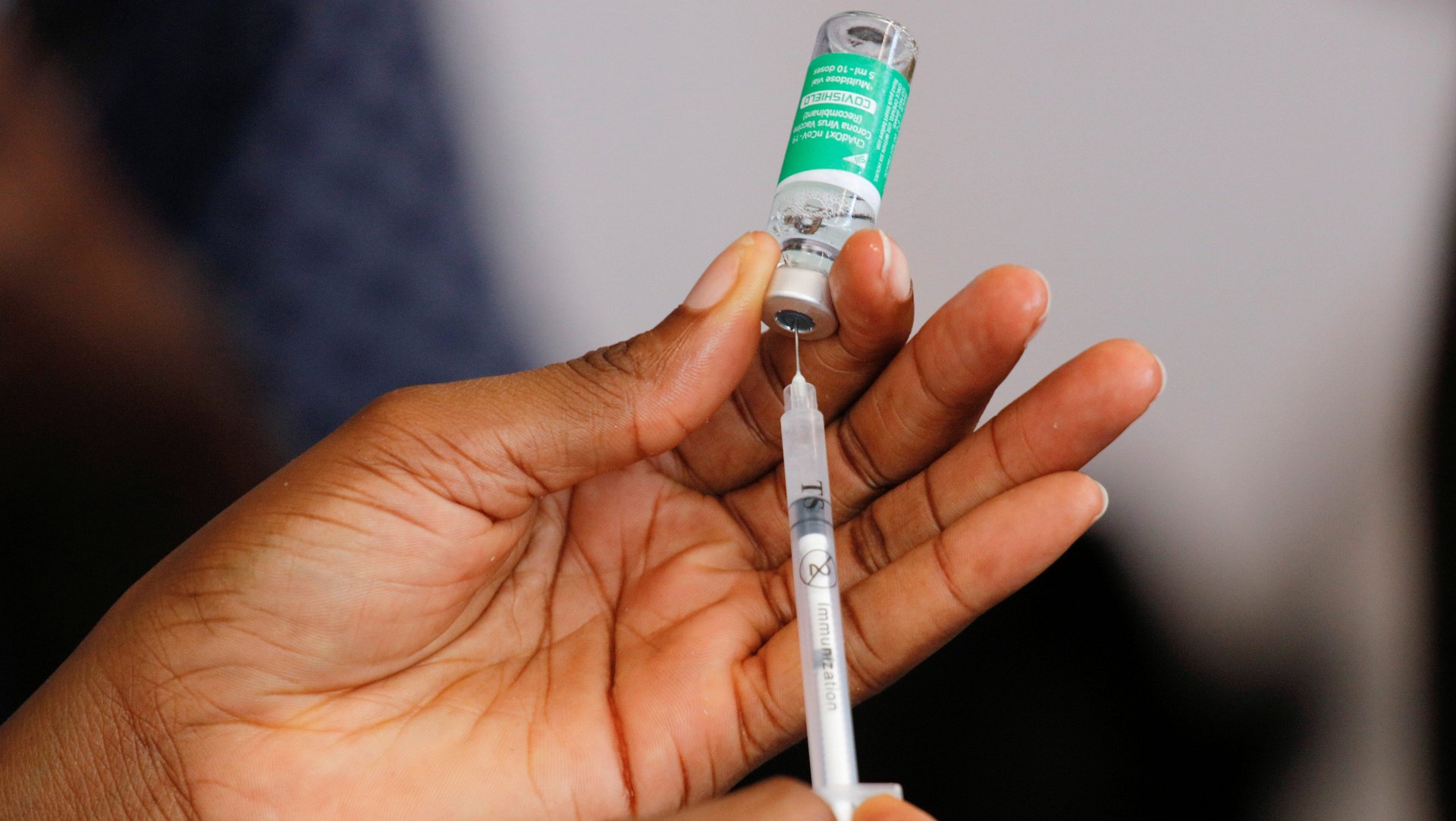

Since the first approval of a Covid-19 vaccine for use by China in June 2020, more than 526.8 million doses of different vaccines have been administered worldwide. But there is a striking divide between continents, with vaccination rates in Africa among the lowest in the world.

Since the first approval of a Covid-19 vaccine for use by China in June 2020, more than 526.8 million doses of different vaccines have been administered worldwide. But there is a striking divide between continents, with vaccination rates in Africa among the lowest in the world.

While the US has administered more than 136.7 million Covid-19 vaccine doses as of the end of March, only about 23.6 million doses have been administered in the entire African continent by mid-month, according to the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC).

Some African countries were gearing up to manufacture approved Covid-19 vaccines for the continents as a way out of this quagmire. But a proposal to temporarily lift World Trade Organization rules protecting intellectual property, which would have allowed countries to more easily manufacture vaccines domestically, was recently opposed by developed countries such as the US, the EU countries, Canada, and the UK.

African scientists believe that the Covid-19 vaccine access challenges experienced by African countries would have been avoided if a vaccine was developed in Africa.

“In the process of this pandemic, did people make an effort to make vaccines in Africa? The reality is, yes they did,” says Dr. Christian Happi, a molecular biologist and genomicist who leads the African Center of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) in Nigeria. “But were those vaccine candidates supported? The answer is no,” Happi says. “Africa didn’t invest in Covid19 vaccine development when we could have produced a vaccine for the African population.”

Medical scientists in Africa often struggle to get funding, with the continent’s expenditure on research and development at 0.5% of GDP lagging the global average of 2.2%. As a result, its healthcare systems are overly dependent on countries in other regions for new drugs and vaccines. Local pharmaceutical companies are also focused on manufacturing generic drugs. It usually takes many months, and sometimes several years, after a new drug or treatment is approved before it is accessible in Africa.

Covid-19 vaccine development in Africa

After news emerged early last year that a new coronavirus was spreading across the planet, over 90 organizations across the world began developing and testing vaccines, resulting in a handful being rolled-out in record time. This was made possible with massive private and public sector investment. The US, for instance, invested more than $10 billion in 2020 to advance vaccine development.

As of September, 321 vaccines were in development, with 33 in clinical trials, according to an analysis by Nature. Around 40% of the development has happened in North America, compared to 30% in Asia and Australia, and 26% in Europe. Africa counts for only a few projects.

This is not just a question of wealth or capacity. Middle-income countries such as India, Cuba, India, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Thailand, and Iran all have vaccines in human clinical trials. Why hasn’t the same happened in Africa’s middle-income countries— Nigeria, Morocco, South Africa, Egypt, Senegal?

Efforts made by African scientists have been underway, but they have failed to get support from either the private or public sector.

Last September, Dr. Happi’s-led ACEGID, which is a World Health Organization and Africa CDC laboratory for genomic research in Africa, announced that it was developing a Covid-19 vaccine with Professor Jonathan Heeney, their partner at the University of Cambridge.

The developmental vaccine was said to identify a neutralizing antibody that could knock down up to 90% of the viruses in a preclinical trial, according to Dr. Happi. Unfortunately, the laboratory has not been able to get funds or support to carry out clinical trials.

“I made a lot of efforts, wrote many proposals and we reached out to many people but it never yielded fruit,” he said. The AU and the Africa CDC are aware of the project but people say they will do something about it and that is the end of it.” Despite this, Happi has plans to continue his research. “I am hoping that someday somebody will see the value in it—probably not an African or African government—and invest in it and sell it to Africans.”

African governments prefer ready-made vaccines

Part of the reason for the lack of funding is that African countries chose to focus on securing delivery of already-developed vaccines rather than creating their own. Led by the AU and Africa CDC, states responded to the pandemic as a common front, employing a strategy which enabled it to pool resources, including in the purchase of ready-made vaccines.

They were able to secure financing from Afreximbank, which is facilitating payments for Covid-19 vaccines by providing advance procurement commitment guarantees of up to $2 billion to the manufacturers on behalf of AU member states. For comparison, the cost of vaccine development, from preclinical testing through to human trials, range from $8 million to $350 million.

There is no report of such financing for the development of a Covid-19 vaccine in Africa (The Africa CDC and the AU did not respond to comment for this article). The AU’s current vaccine development and access strategy has been limited to supporting clinical trials and accelerating post-trial product regulatory decisions, roll-out, and uptake. So far, Covid-19 vaccine clinical trials done in Africa have been through foreign organizations such as Novavax, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

“We have the human resources, we have the know-how; we have the intellectual capacity, but we don’t have the political will to mobilize the resources to make it happen.” Dr. Happi said. He believes that a preference to buy imported vaccines rather than develop and produce them is a legacy of colonization. “For Africans, anything that comes from overseas is best.”

The current structure of research funding doesn’t help, says Gerald Mboowa, a bioinformatics researcher at the Makerere University in Uganda and infectious disease specialist.

“Many research facilities across Africa are funded majorly by the western countries and this means that most of the research agenda is dictated by these countries and not African countries,” says Mboowa. “African researchers generate data for these funders which is then used to manufacture value-added innovations [and] products that again get sold back to the continent.”

Mboowa explained that due to African research being dictated by western agenda, local institutions will not be able to address local health and technological challenges. “African technological innovations are being undermined or discouraged while creating a market for western-led innovations/products.”

Lack of political leverage

This geographic imbalance of vaccine development has naturally manifested in unequal distribution. Africa accounts for the lowest number of doses that has been administered per 100 people (only 0.7 doses), compared to 5.0 doses for Asia, 8.0 doses for South America, 16 doses for Europe, and 27 for North America. At the current rate, the continent is expected to only reach herd immunity in 2023 at the earliest.

Efforts to vaccinate the global population have been marred by “vaccine nationalism” and “vaccine apartheid,” where wealthy countries developing and producing the vaccines have prioritized their populations, and have been accused of undermining efforts being made to increase access for other countries.

That’s left most African countries relying on donations from countries like China and India, or the global vaccine-sharing arrangement COVAX, which has promised enough vaccine doses to cover 20% of the country’s population by the end of 2021. The African Union announced in January that it has secured a provisional 270 million Covid-19 vaccines for about 10 to 15% of the continent’s population. African governments are currently faced with the daunting challenges of figuring out how to fill in the gaps.

African scientists have the expertise and experience to deal with fast-moving infectious diseases and have made efforts to develop solutions such as a Covid-19 vaccine. Imagine how the fight against the pandemic would have looked if African governments were as nimble, and had funded a local vaccine instead of solely relying on vaccines made elsewhere.

The successful development of Covid-19 vaccines in Africa would not only have given African countries more political leverage to access more vaccines. It would have also encouraged more investment in local innovations and products for other diseases and healthcare challenges in the continent.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation in your inbox.