Online shopping is taking hold in mall-loving South Africa

The pandemic has jump-started e-commerce in South Africa.

The pandemic has jump-started e-commerce in South Africa.

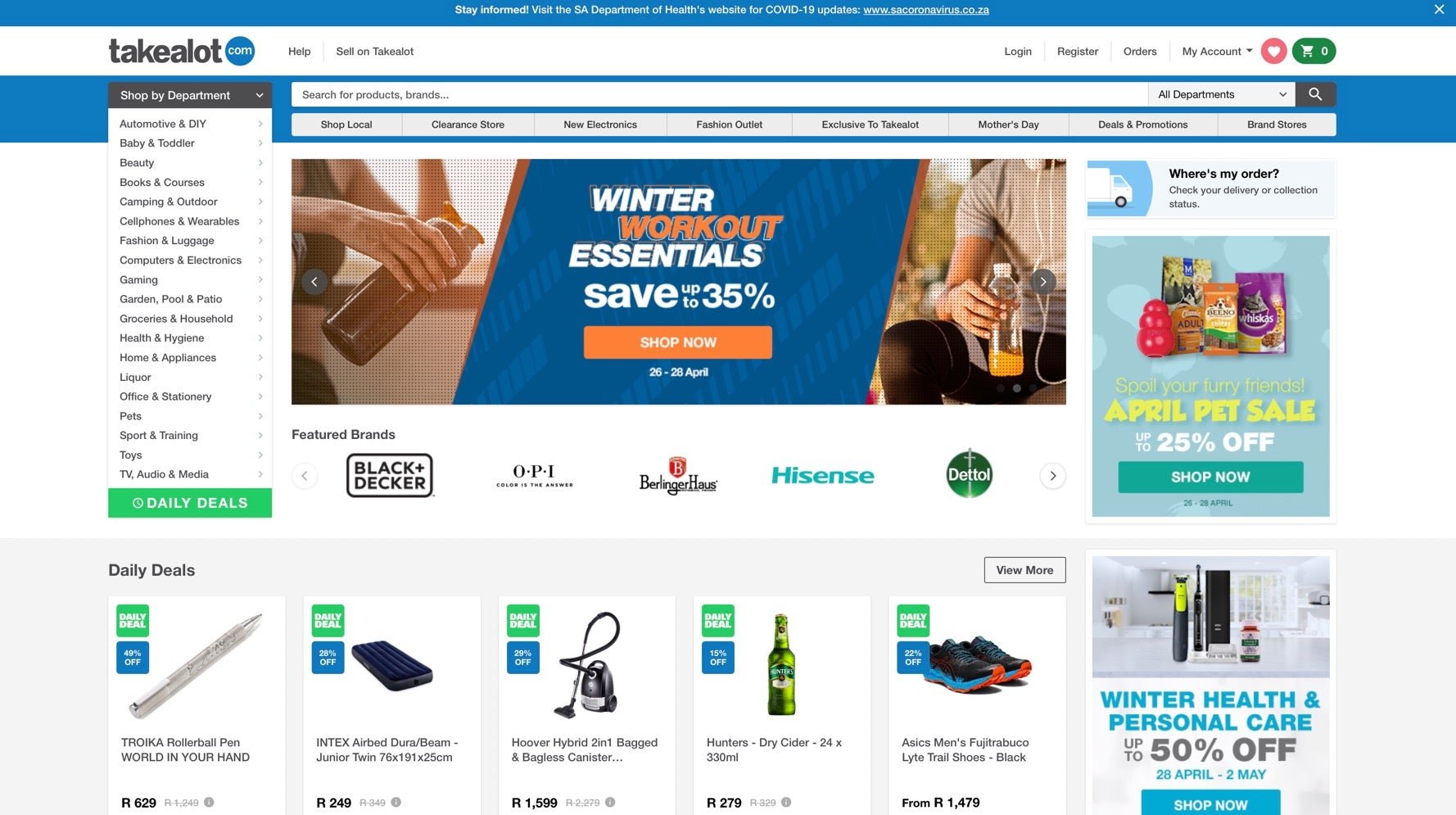

One of the biggest winners may be Takealot.com, a local e-commerce website that launched nearly a decade ago and later became part of Naspers, Africa’s biggest company by market capitalization. Revenue at Takealot reached $238 million in the six months that ended Sept. 30, its most recently reported period. That’s up 41% from the same period a year earlier.

Developments such as same-day delivery of groceries and the ability to collect packages when and where convenient have paved the way for a growing number of South Africans to carry on from the comfort of home amid varying levels of a nationwide lockdown designed to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus.

The acceleration of e-commerce in the country highlights improvements in how retailers get goods to consumers. It also stands out for being largely homegrown. The US retail giant Amazon has no e-commerce in Africa despite serving thousands of cloud computing customers on the continent and recently receiving local approval to build an African headquarters in Cape Town. Jumia, Africa’s largest e-commerce operator, serves South Africa via its fashion retailing site Zando but pales in its presence there compared with local rivals.

Shaking a love for shopping malls

E-commerce in South Africa has had a slow start, in part because South Africans have long loved their shopping centers. The country ranks among world leaders in malls per capita, and South Africans flock to them for safe places to shop, to unwind, and to be seen.

Consumers across the world made more of their purchases online during the pandemic. And while malls still have their lure for South Africans—sales of luxury brands at malls such as the upscale Sandton City Shopping Center in Johannesburg boomed last year—moves by retailers to improve last-mile delivery suggest online shopping may finally be taking root. “We saw between 50 and 70% growth in e-commerce in South Africa in 2020,” says Arthur Goldstuck, managing director of World Wide Worx, a Johannesburg-based technology market research organization. “Originally, we had anticipated growth would be about 25%.”

Estimates of the number of South Africans who shop online vary by income and location. The lion’s share occurs among consumers who populate cities and larger towns such as Johannesburg and Cape Town, compared with those who live in the country’s rural areas, notes Goldstuck. He adds that the sharp growth in online sales over the past year also reflects a low starting point.

For its part, Takealot sells and delivers a variety of merchandise directly from manufacturers as well as on behalf of smaller retailers and other third parties. The platform now accounts for at least a quarter and possibly as much as half of South Africa’s online retail, according to Goldstuck. “They are essentially the Amazon of South Africa,” he says.

Analysts credit Takealot’s pre-pandemic investments in warehouses and distribution centers for readying the retailer to handle the wave of demand triggered by the coronavirus. The company’s initiatives have included the purchase of the food delivery service Mr. D Food in 2014 (think logistics), as well as the launch two years ago of pickup points located next to some of South Africa’s busiest highways, which let consumers collect and return online orders at their convenience.

“That’s quite a big shift in their model in terms of improving the customer experience, and in some ways the move from a pure delivery model to a collect model as well helps to reduce their costs,” says Neelash Hansjee, a senior portfolio manager at Old Mutual Equities in Cape Town. He adds that Takealot also has broadened the selection of merchandise for sale on its platform, which features 19 departments that include appliances, computers, electronics, fashion, health, sporting goods, toys and TVs. “It’s now, how do you leverage that growth post-Covid, and where do you go from here?” says Hansjee.

Walmart in the mix

Takealot’s rivals are intensifying their push to gain some of that market share. Chief among them is Massmart, which operates both physical and online retail stores chiefly under the Game, Builders, and Makro banners in South Africa and 12 other countries in the region. In its latest presentation of financial results, Massmart noted that online sales at Game, Builders, and Makro rose 77.5%, 111%, and 40.2%, respectively, in the year that ended December 27, though the company did not report online sales as a percentage of total sales at each business.

Massmart, which tops Takealot in sales thanks to the former’s brick-and-mortar stores (Game alone logged nearly $1.2 billion in sales last year), is about 18 months into a turnaround after losing money two years ago for the first time in its then 29-year history. It is drawing heavily on the know-how and experience of its majority shareholder, the US-based retailing giant Walmart, as it works to right its business and bolster its digital capabilities.

As a result, analysts are not counting Massmart out of e-commerce battles to come. Mitchell Slape, Massmart’s CEO, ran operations and e-commerce for Walmart in Japan before taking the helm last year in South Africa. In October, a month after Slape arrived, Massmart named a new head of e-commerce who previously oversaw last-mile delivery for Walmart in North America.

Walmart has battled Amazon for years in the US, where Walmart dominates brick-and-mortar retail. “Walmart knows how to compete in this world, and that’s something that the guys here locally can leverage,” says Hansjee. “They already have the big physical distribution in place. Now they have to leverage their online capability to get people to shop there.”

For its part, Jumia generated just about 14% of the revenue in South Africa and in four other eastern African countries ($32.6 million) last year that Takealot, which does not ship beyond South Africa, earned in its most recently reported six months. To avoid missing out on the country’s growing appetite for convenience, Uber Eats last year expanded its food-delivery service to handle deliveries of over-the-counter medications, packages, and groceries in some locations.

Supermarkets speed up

Though Takealot, Game and Makro all sell non-perishable groceries, South Africa’s supermarket chains also have doubled down on digital shopping and delivery in the past year as demand for online ordering skyrocketed.

Shoprite Holdings, which operates supermarkets across South Africa under the Checkers, Checkers Hyper, and Shoprite banners, has upped its investment in its “Sixty60,” service, which delivers groceries within an hour from 150 of its roughly 241 Checkers stores nationwide. The chain also offers scheduled delivery to customers in and around Johannesburg and Cape Town. In April of last year, Checkers teamed with Takealot’s Mr. D Food to deliver from 55 of the supermarket chain’s 90 pharmacies.

Rival Pick n Pay, which offers online delivery from 140 of its 295 company-owned supermarkets nationwide (the company also franchises stores) as well as so-called click-and-collect online-order, in-store pickup, has doubled down on speedy delivery as well. In October, the chain bought Bottles, an online liquor delivery service that Pick n Pay retooled for same-day grocery delivery from 95 stores. Last April, Pick n Pay opened an online store for its retail clothing business.

While neither Shoprite Holdings nor Pick n Pay break out online shopping as a percentage of total sales, Pick n Pay reported recently that online sales more than doubled over the year that ended on February 28. The company also said it intends to accelerate its investment in digital, starting with a move to unify its online services under the banner of PicknPay.com. “Customers will in future be able to shop seamlessly with Pick n Pay anytime, anywhere and in whichever way they choose,” said Richard Brasher, the company’s outgoing CEO, who agreed last year to stay beyond his term to lead the company through the pandemic.

Financial results at Woolworths Holdings, another rival, shed further light on the size of online grocery sales as they more or less stand. Woolworths, which operates roughly 348 food stores in South Africa, reported in February that 2.2% of its food sales and 4% of its sales of fashion, beauty and home items (the company has about 212 such stores) took place online in the six months that ended December 27, 2020. Click-and-collect service that Woolworths offers in 75 of its stores accounted for at least 25% of online food sales during the period.

To keep pace with rivals, Woolworths in December launched a trial of a same-day delivery it calls Dash at 18 stores in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban. The Cape Town-based retailer reported that the trial had been “operationally challenging” as capacity and on-time delivery fell short of both the company’s own expectations and demand but emphasized it plans to increase investment in selling via online channels.

Analysts say that trials like Dash highlight the significance of delivery networks as a differentiator. “Suddenly we have a new e-commerce world in South Africa in terms of deliveries,” says Goldstuck. “The old way of retailers being able to take their time and deliver in a week is history.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation in your inbox.