Why the omicron variant isn’t sending South Africa back into lockdown

South Africa is refusing to order lockdowns to combat the new omicron coronavirus variant, labeled a variant of concern by the World Health Organization. Leaders in South Africa, where the variant was first sequenced, are instead calling for calm. “We…know that the coronavirus will be with us for the long term,” said South African president Cyril Ramaphosa in public remarks on Nov. 28. “We must therefore find ways of managing the pandemic while limiting disruption to the economy and ensuring continuity.”

South Africa is refusing to order lockdowns to combat the new omicron coronavirus variant, labeled a variant of concern by the World Health Organization. Leaders in South Africa, where the variant was first sequenced, are instead calling for calm. “We…know that the coronavirus will be with us for the long term,” said South African president Cyril Ramaphosa in public remarks on Nov. 28. “We must therefore find ways of managing the pandemic while limiting disruption to the economy and ensuring continuity.”

Ramaphosa, who criticized travel restrictions on South Africa and other countries in the region by the UK, US, and others, declined to tighten domestic lockdown measures. That leaves South Africa at “alert level one” of a five-tier lockdown strategy including mask mandates, a 12 AM-4 AM curfew, and ban on indoor gatherings of more than 750 people.

The latest variant comes after three earlier rounds of strict lockdowns in South Africa that crippled the country’s economy, especially for the urban poor and unemployed. South Africa’s politicians appear unwilling to bear the economic cost of another lockdown. The nation will now rely on vaccines and testing as their primary tools to fight the spread of the virus. The strategy may signal a new era in the fight against covid-19 globally.

As nations adapt to the pandemic, and the goal moves from defeating the virus to managing it, other leaders are following suit. US president Joe Biden and UK prime minister Boris Johnson have also spurned lockdowns for a combination of less disruptive strategies that protect public health.

The economic toll of another strict lockdown

Covid-19 hit the income of South Africa’s poorest citizens the hardest. While the country’s first lockdown slowed infection rates, it devastated a struggling economy suffering from 30% unemployment. By August of 2021, South Africa’s unemployment rate had risen to 34%, the highest in the world. The nation’s informal workers— the 18% of South Africa’s civilian labor force in jobs like street food vendors, market salespeople, and waste collectors—were especially vulnerable due to the in-person nature of much of this work.

In the eastern coastal city of Durban (pdf), for example, a quarter of people work in the informal sector. A survey of their experience during the pandemic found that during the first lockdown in April 2020, 74% to 95% were out of work. By July 2020, even after official restrictions eased, workers’ incomes had not recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Emergency cash and food assistance offered by the government failed to reach more than half of the city’s informal workers.

Talita Greyling, an economics professor at the University of Johannesburg, says that she believes no part of the economy—small businesses, tourism, restaurants—would be able to withstand another lockdown. These economic anxieties are reflected in public sentiment about pandemic policies; Greyling found that South Africa’s Gross National Happiness index, real-time data on personal well-being, dropped 5% on Nov. 26 when the omicron variant was announced by the World Health Organization and people awaited government action. When the president announced a couple of days later that lockdown measure wouldn’t be tightened, the index rebounded immediately.

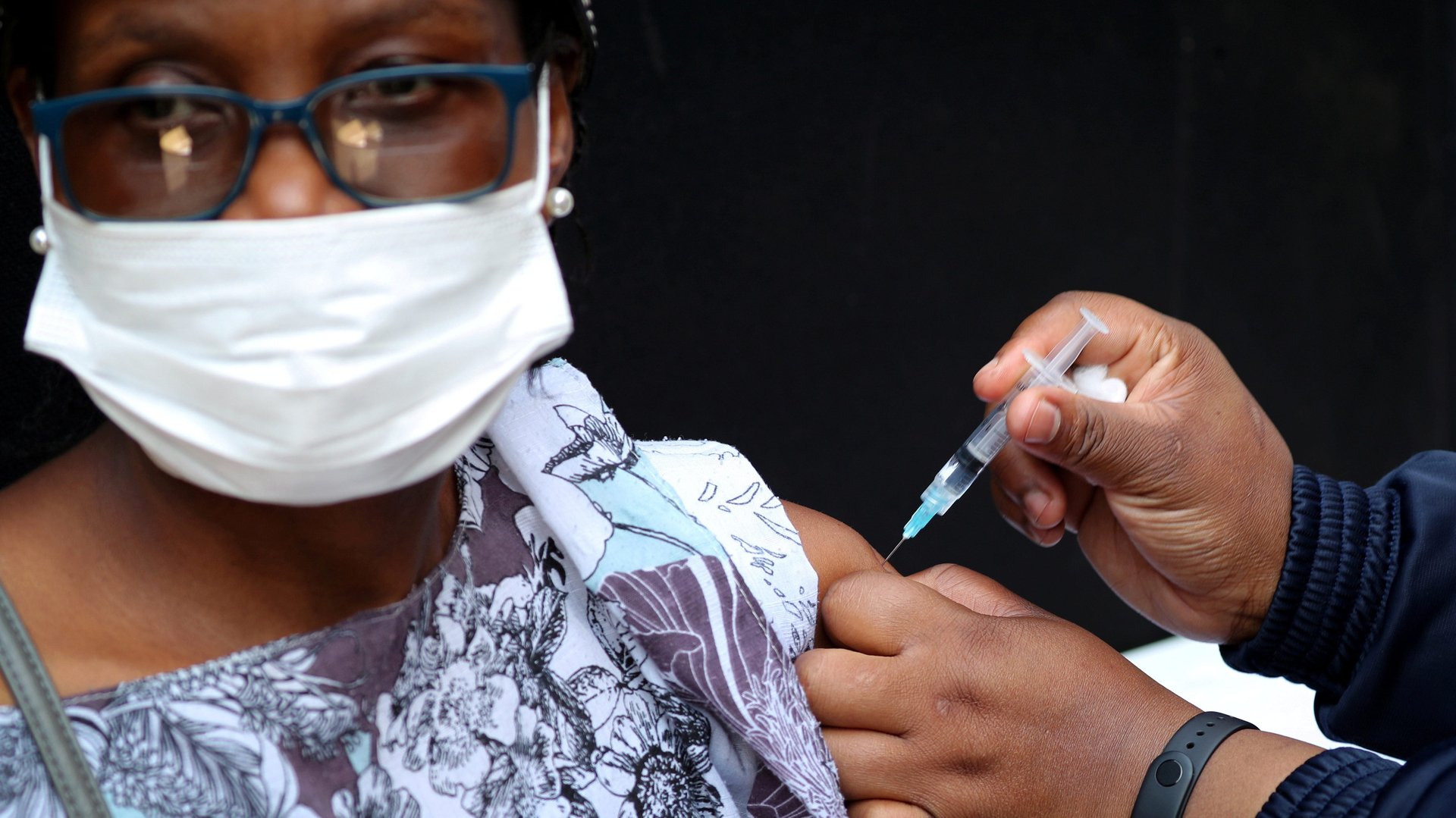

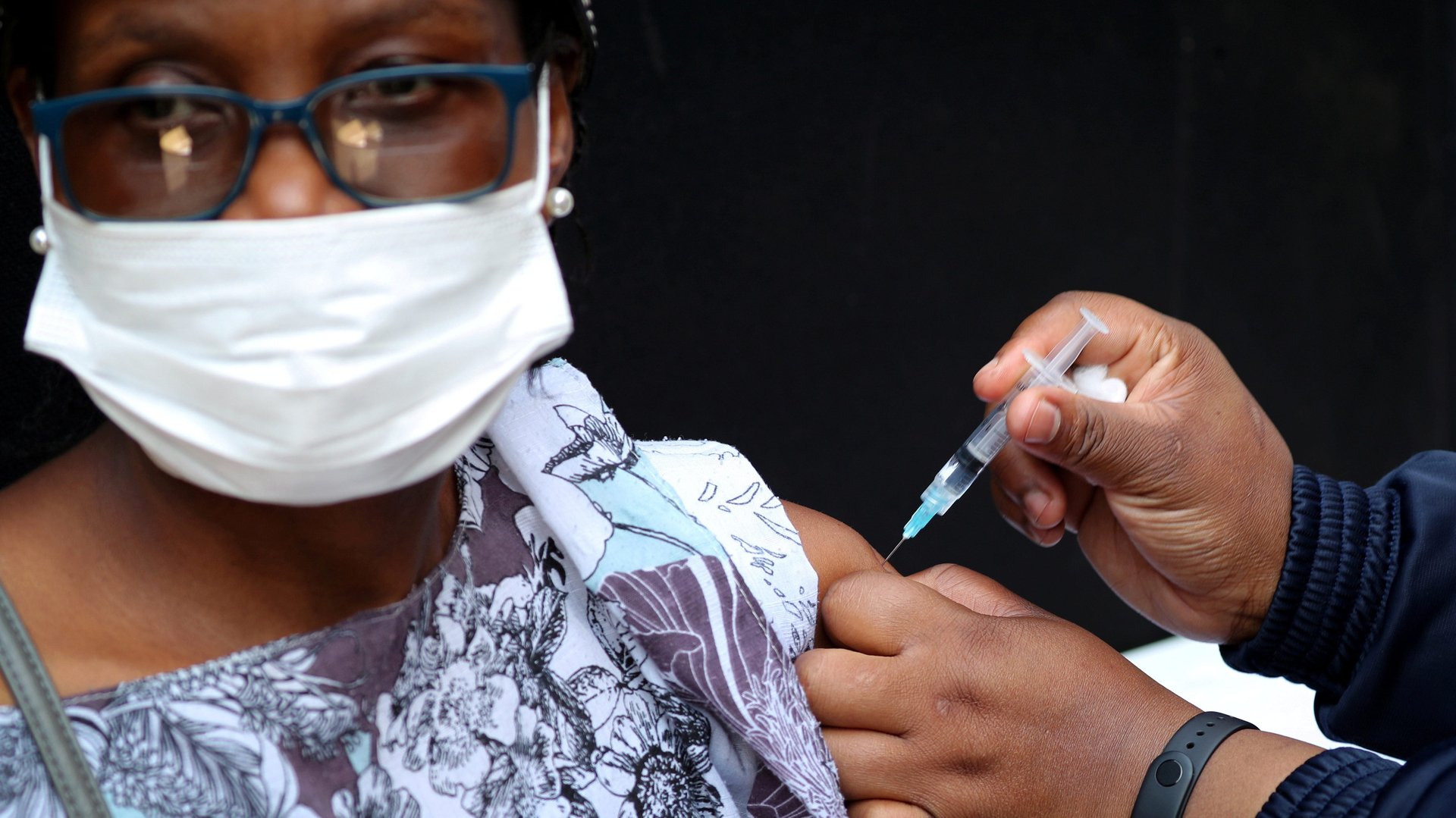

South Africa is betting big on vaccines

President Ramaphosa is counting on vaccines, previously unavailable during the first waves of the pandemic, to be the primary tool to fight transmission this time around. About 41% of adults in the country have been fully vaccinated according to government data, but officials are working to get that number higher. The president has established a task to explore vaccine mandates for certain public venues. Local jurisdictions are following suit; provincial governments have staffed up testing and vaccination infrastructure in hospitals, and city governments in Cape Town and Johannesburg continue to carry out vaccination campaigns.

South Africa’s vaccination push is also complicated by international inequality in vaccine distribution earlier in the pandemic. While the country currently has an adequate supply of doses, it only began widely distributing vaccines in May of 2021, six months after wealthier Western nations began protecting their citizens. South Africa, as well as other African nations, are now having to catch up as a new variant circulates.

Even as scientists work to figure out just how responsive this new variant is to existing vaccines, politicians in South Africa, as well as Western countries are still offering vaccination and testing as the best way to keep people safe. If travel bans and lockdowns are seen as unsustainable responses to a disease that is expected to remain with us indefinitely, these may very well become the only strategy going forward.