MoMA celebrates a ground-breaking Ivorian artist who drew a new language

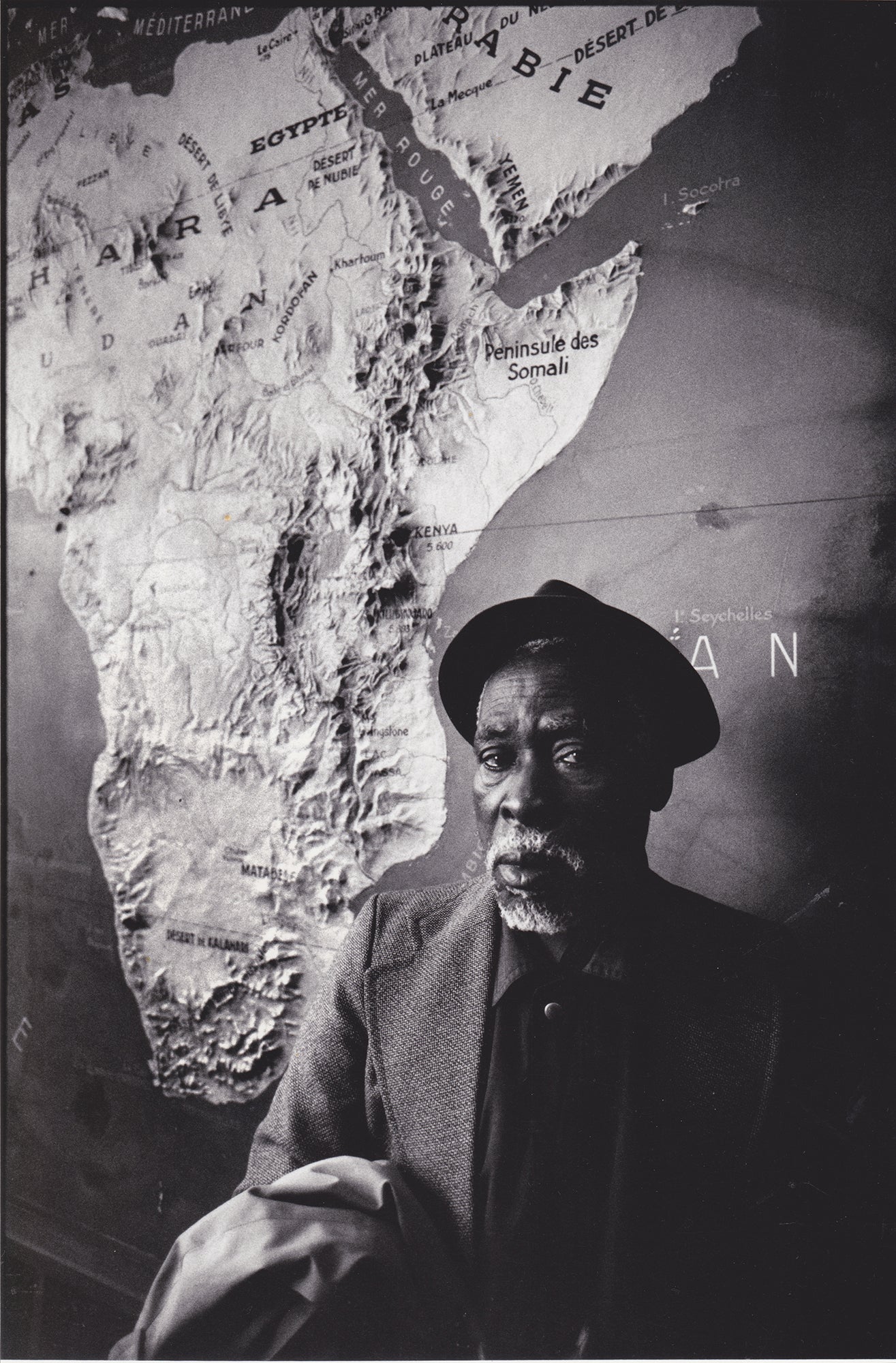

In 1948, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, a young Ivorian former colonial navy officer, living in Dakar, Senegal—then the capital of French west Africa—had a vision. The skies opened up, revealing seven suns dancing around a central star. Bouabré changed his name to Cheik Nadro, “the Revealer,” and dedicated his life to inventing a new writing system for his people, the Bété.

In 1948, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, a young Ivorian former colonial navy officer, living in Dakar, Senegal—then the capital of French west Africa—had a vision. The skies opened up, revealing seven suns dancing around a central star. Bouabré changed his name to Cheik Nadro, “the Revealer,” and dedicated his life to inventing a new writing system for his people, the Bété.

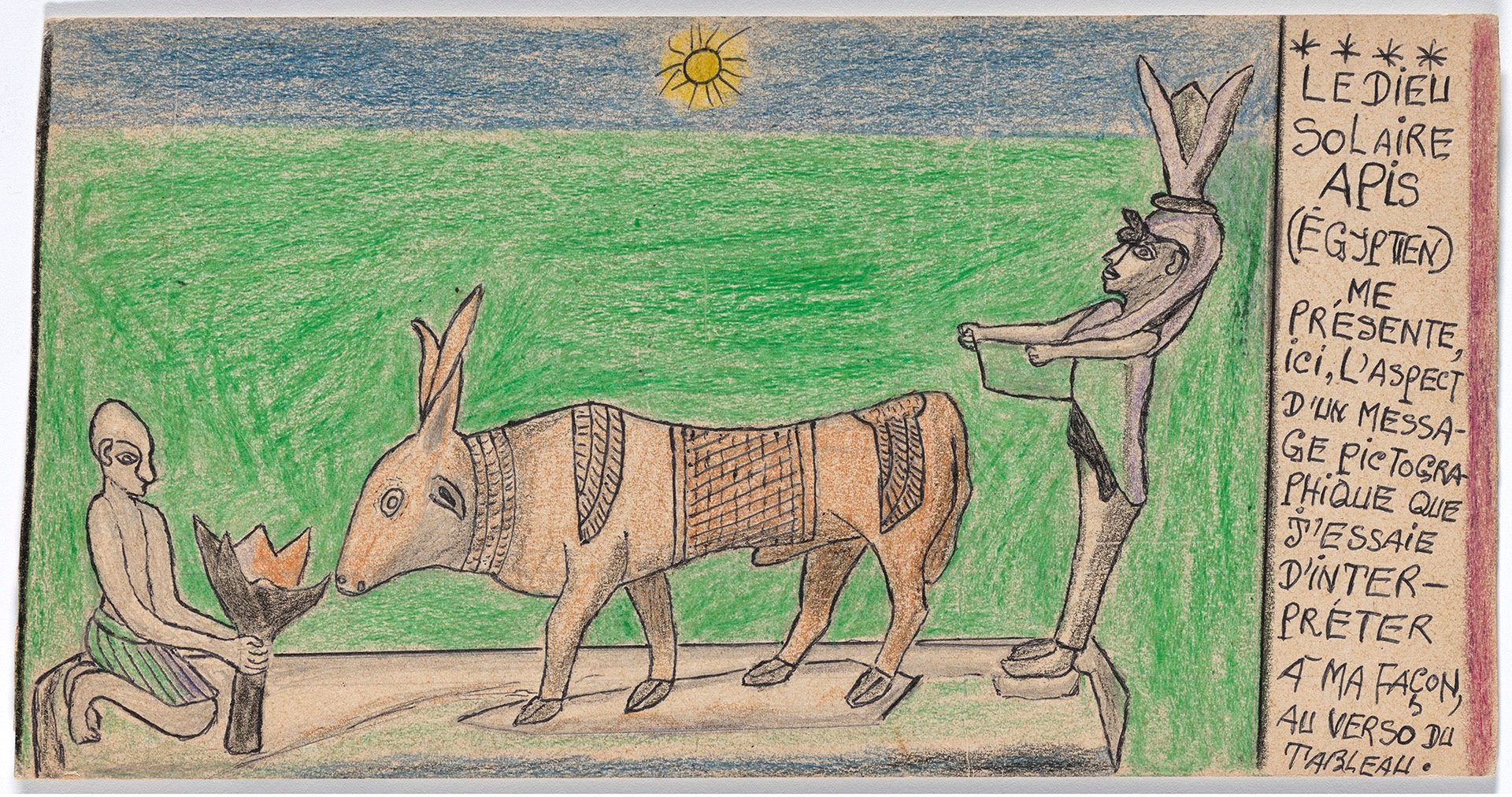

Bouabré is the first Ivorian artist to have his work showcased in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which will be on display through Aug. 13, 2022. The exhibit pays homage to Bouabré’s decades-long career, showcasing 11 series of drawings totaling more than 1,000 individual works, including his two best-known bodies of work, Alphabet Bété (1990-91) and Connaissance du monde (1987-2008.)

“Frederik’s work transcends discussions around fluidity versus balkanization. He shows language to be a living, breathing, evolving thing,” Uzodinma Iweala, the CEO of the Africa Center in New York (formerly known as the Center for African Art) told Quartz. “It forces us to ask the question, who is the arbiter of what is taught and what we see as knowledge?”

Language in Africa is a complicated topic

Language and the written word is something that dominates African literary discourse. The continent has a complicated relationship with the various lingua franca in wide use, which has been a rich source of artistic, and political inspiration.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Kenya’s world-renowned author, shuns writing in English and instead writes in Kikuyu and then has that translated. Ousmane Sembene—the godfather of African cinema—chose to focus on films rather than novels to reach the illiterate masses, because he understood that the written word in Senegal was the preserve of the few who had received a colonial education.

In 2004, Joaquim Chissano, then the president of Mozambique, had government officials scrambling to find translators when he decided to give his farewell speech as the chairman of the African Union in Swahili. At the time, the AU was only using English, Portuguese, Arabic, and French as its official languages.

Africa’s literary tradition has long been undervalued

One school of thought says that oral history was the dominant form of collective memory in Africa for generations and unless we concentrate on written language now, we will always be the proverbial lion in stories told about us by the hunter.

The more recent line of thinking is that different literary forms have always existed on the continent, but have been complicated or erased by outside perspectives. The elaborate 10,000-year-old rock paintings in the Laas geel caves in Somaliland are barely spoken of as examples of early art. Proof of great ancient civilizations including the Egyptian empire, and the Great Zimbabwe ruins suffer from a long legacy of the erasure of Black Africans. Some—including Elon Musk—even prefer to credit their creation to aliens from outer space.

One of the world’s largest collections of ancient manuscripts are from Timbuktu in modern day Mali. In many instances, written tradition in Africa predates that of modern Europe. These are uncomfortable truths for many. Acknowledging the complicated legacy of the African artistic and literary tradition shakes the very foundations upon which our current global economic and social structures have been built, challenging racist assumptions about what constitutes both art and scholarship.

Moving the discussion forward, African thinkers are asking what now? Now that these are the languages we speak, shall we discard them, or Africanize them, or accept that they are now part of us?

“I don’t see French as a colonial language,” said Ivorian writer Renée-Edwige Dro in a Zoom panel discussion on the Frédéric Bruly Bouabré exhibition. “Me and my people have taken it and appropriated it for ourselves. We can speak French in front of French people and they will not understand what we are saying.”

Throughout the continent, there are examples of millions making languages that were thrust upon them and come with heavy colonial baggage, fully theirs. Frédéric Bruly Bouabré’s World Unbound exhibition allows the viewer to contextualize this through history and confront our own biases on what the continent’s literary journey is and has been.