Ethiopia’s economy is roaring but its democratic process continues to whimper

Last Sunday Ethiopians went to the polls in the first general elections since the death of long-time strong-man Meles Zenawi.

Last Sunday Ethiopians went to the polls in the first general elections since the death of long-time strong-man Meles Zenawi.

Unlike the elections in fellow African nation Nigeria in March, there was no breathless anticipation with the Ethiopian elections, despite the potential historic significance of the vote. Whereas the outcome of the Nigerian elections was legitimately uncertain prior to the tallying of the votes, the results of the elections in Ethiopia, Africa’s second most populous country, were a foregone conclusion.

The official results will not be released until June 22 but the preliminary results seem to confirm the popular consensus that these elections would further consolidate the power of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (the EPRDF) with Hailemariam Desalegn returning as prime minister. The party has dominated the country’s political atmosphere since coming to power over two decades ago. Other than an AU delegation, no international observers were granted accreditation to observe the elections; in its final report the AU conspicuously avoided the terms ‘free and fair,’ instead describing the elections as “calm, peaceful, and credible.”

One of the most striking explanations for the EPRDF’s dominance is the state of Ethiopian civil society and media, which is too stifled to provide a check on the government’s power or call-out electoral improprieties. Ethiopia has done all that it can to stifle dissent and silence its critics. In 2009, the country adopted the Charities and Societies Proclamation 621/2009, which prohibits foreign NGOs from working on issues related to human rights, democratic governance, or conflict resolution. The law also classifies domestic groups that receive significant funding from foreigners as ‘foreign groups.’

Similarly, the country has used the innocuous sounding Anti-Terrorism Proclamation to stifle domestic media. Between 2011 and 2013, the law was used to prosecute eleven journalists; the Committee to Protect Journalists reported 17 journalists spent time in jail and 30 fled the country. In the 2010 elections, opposition parties garnered just one seat in the 547-seat parliament.

Reflecting on the 2015 electoral landscape, Professor Merera Gudina, of the opposition party Oromo People’s Congress notes, “No more than two to three parties are real opposition parties. The others don’t run to win. Their role is to dilute the vote for the opposition.” The country has also barred international observation groups from conducting electoral observations, casting further doubts on the quality of the 2015 elections. The result of the legislative and physical stifling of dissenting voices in Ethiopia is that “for most Ethiopians, these elections are a non-event.”

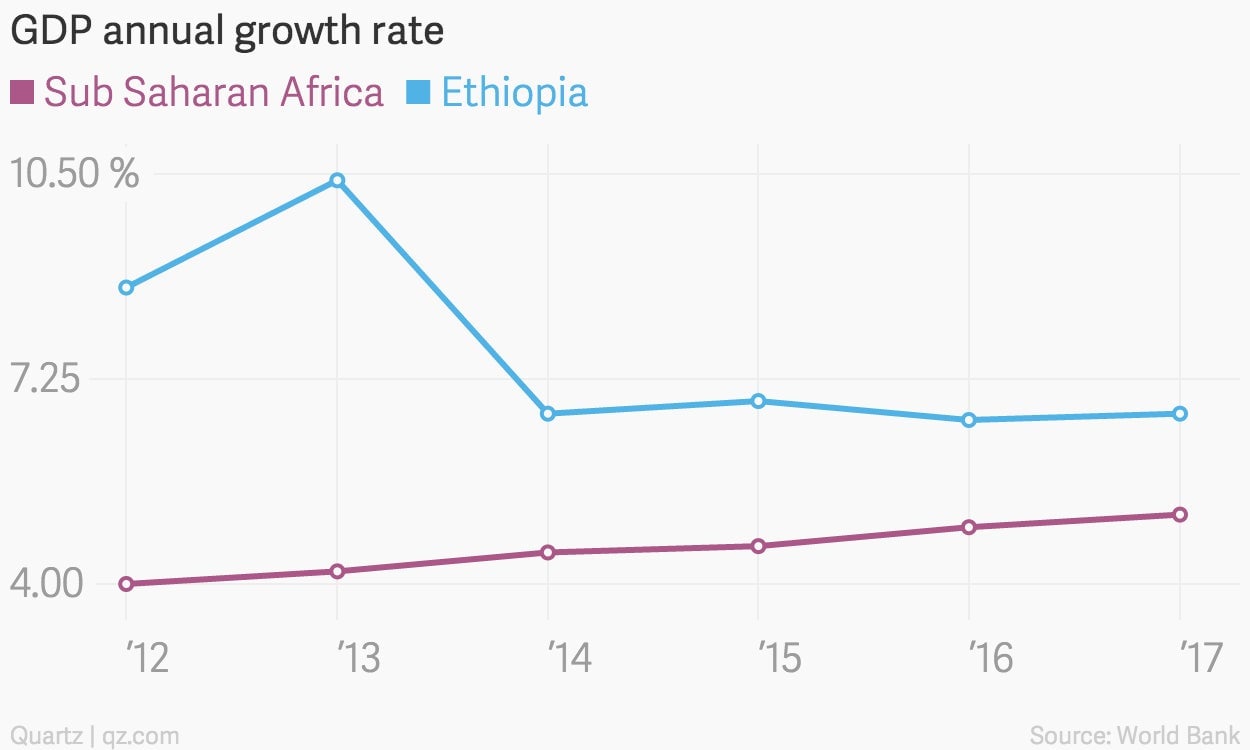

While civil society has been stunted in Ethiopia, its economic growth has charged ahead. Between 2003-2013, the country averaged a growth rate of 10.8% — more than twice the regional average of 5.3%. The country’s growth has been driven not just by agriculture, but also by industrial production and the services industry – a rare example of economic diversification in Sub-Saharan Africa. EPRDF has has been instrumental in brokering deals with international investors and directing government investment into productive sectors.

The IMF has classified Ethiopia as one of the five fastest growing economies in the world. Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, has been described as ‘the Dubai of Africa.’ The construction boom in Addis Ababa is a microcosm of the country’s overall transformation; Africa Business Pages writes “hotels, shopping centres, and office complexes rise from where small shacks once stood… tall incomplete buildings are visible as far as the eye can see.” Ethiopia boasts the African Union’s headquarters, housed in a flashy, new, 50,000 square meter facility built by the Chinese as a “$200 million gift.” Ethiopia is also partnering with Chinese companies to expand the Bole International Airport; a $300 million deal with China Communication Construction Company Ltd is projected to triple the number of passengers the airport can handle to 21 million annually, making it one of 30 busiest airports in the world.

Just as Rome was not built in a day, democracy is not constructed with the casting of ballots; the development and engagement of a robust civil society is a critical step in democratic consolidation. It is certainly not the case that international support alone can produce the sort of civil society that demands democratic institutions, but it would be foolish to disregard entirely the international community’s role in promoting the development of such groups and demanding legal protections for their rights to free speech. That President Obama plans to visit Ethiopia, rather than Nigeria, in his next Presidential visit to Africa, underscores the low priority given to democratic legitimacy in American foreign policy.