The real story behind China’s alleged conquest of African farmland

The year is 2006. Deep in the African bush, drums beat while dancing women lead a delegation of Chinese officials to a set of soft armchairs lined in rows inside a large tent. Outside, a brass band strikes up the national anthem of Mozambique as newly elected President Guebuza steps up to a microphone to make a few brief remarks. Guebuza then turns the podium over to Mapito, the organizer of the meeting. “Listen carefully,” a Chinese businessman whispers to his sister. “This is what the future will look like.”

The year is 2006. Deep in the African bush, drums beat while dancing women lead a delegation of Chinese officials to a set of soft armchairs lined in rows inside a large tent. Outside, a brass band strikes up the national anthem of Mozambique as newly elected President Guebuza steps up to a microphone to make a few brief remarks. Guebuza then turns the podium over to Mapito, the organizer of the meeting. “Listen carefully,” a Chinese businessman whispers to his sister. “This is what the future will look like.”

After taking a sip of water, Mapito describes a planned helicopter trip along the Zambezi River. “We shall fly over fertile areas that are sparsely populated. According to the calculations we have made, over the next five years we will be able to accommodate four million Chinese peasants who can farm the areas currently lying fallow.”

That afternoon, with the thundering clatter of the helicopters drowning out the possibility of conversation, the delegation flies over what appears to be an enormous untouched wilderness. The sea of dark green is broken only by the winding route of a silver river and a scattering of settlements. Later, after dinner, another troupe of local women dance in the firelight. “I take it,” the sister says to the Chinese businessman, “that everything’s been prepared already.”

The scenes described above are fiction. They appear—far more elegantly—in a best-selling thriller published in 2008: The Man from Beijing, by the Swedish writer Henning Mankell. The meeting in the jungle never happened. Only in a novel would an elected political leader support a plan to import four million Chinese into his country. Mankell’s story reflected exaggerated Western fears about China in Africa, fears that took visual form in the famous March 15, 2008, cover of the Economist, with a Photoshopped picture of pith-helmeted Chinese men riding camels across the desert under the banner title: The New Colonialists.

A slightly less sensational story about the Zambezi valley surfaced in August 2007, when a website hosted by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology published a short article on China’s growing ties with Mozambique. Nearly a year later, the prominent Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC posted a second short article by the same author with the title, The Zambezi Valley: China’s First Agricultural Colony?

The websites appear to have provided no fact-checking, or editorial or peer review. Nevertheless, the two articles created a powerful narrative that would be picked up as fact by NGOs, think tanks, government agencies, and magazines. This story would ultimately become one of the key planks in the foundation of the West’s understanding of Chinese intentions in rural Africa. Yet, as we will see, this plank had some very large cracks.

Here is the story as sketched out on these two websites. The Chinese government was “aggressively” seeking large land leases along the Zambezi River valley, trying to “induce” Mozambican officials “to allow them entry into the valley.” The Chinese, “crude and rapacious businessmen scavenging for raw materials,” were able to “open doors otherwise closed to Western nations.” In 2006, the author said, China had given Mozambique a loan of $2.3 billion to build Mpanda Nkua, an enormous dam on the Zambezi River. The two governments, he said, had signed an agreement to allow “as many as 20,000 Chinese settlers” to “move into the valley to run large- to medium-scale farms destined to supply the ever more affluent Chinese market.”

These farms would be China’s “first agricultural investments in Africa.” However, the plan to import Chinese settlers “caused great outrage locally” because people in the Zambezi valley feared a return to the dark days of Portuguese colonialism. Indeed, reports of the deal caused “such an uproar” that the Mozambique government was forced “to dismiss the whole story as false.”

Nevertheless—the author wrote—the two governments were quietly proceeding with their plans. The government of Mozambique had even decided to make Mandarin a compulsory foreign language for all high school students. The Chinese government had pledged (the author said) to add another $800 million to the earlier loan—a commitment of over $3 billion—all focused on modernizing rice production in Mozambique. Chinese offers of finance for agricultural research and road projects in Mozambique were also “clearly designed to maximize production and facilitate the rapid export of foodstuffs to China.” The rice must be meant for China, the author argued, since Mozambicans do not eat much rice.

As further evidence of Chinese intentions, he wrote, China had abolished import tariffs on 400 agricultural products from Mozambique, including rice. “One thing seems to be certain,” he emphasized, “China is committed to transforming Mozambique into one of its main food suppliers, particularly for rice.”

Although it would turn out to be laced with errors, publication on the website of CSIS, one of the world’s most respected think tanks, gave the story credibility, while the timing, during the height of the world food crisis, gave it instant visibility. The argument that the Chinese government was leading an aggressive effort to acquire large expanses of land in Mozambique, hoping to settle tens of thousands of Chinese citizens there to grow rice to send home to China, was accepted nearly everywhere, without question. In Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute researchers wrote that “Mozambicans have resisted the settlement of thousands of Chinese agricultural workers on leased lands,” citing the CSIS story as their source.

The German development agency GIZ included the story in a list of reported foreign investments in land, noting that it was discontinued “due to political opposition.” It was cited by newspapers, think tanks, NGOs, and researchers, appearing in reports by GRAIN, the Land Matrix, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, and South Africa’s Standard Bank. Magazines, including the Atlantic, repeated the story. In August 2008, the US embassy in Maputo even quoted parts of the CSIS website story in a secret diplomatic cable sent back to Washington.

Only one report commented on the curious lack of evidence. The London-based International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) had done fieldwork on foreign land grabs in Mozambique and other countries while carrying out a major study for the FAO and the International Fund for Agriculture (IFAD), published in 2009. Citing the CSIS story on China and Mozambique, they noted pointedly that they had been unable to verify its claims. “A common external perception is that China is supporting Chinese enterprises to acquire land abroad as part of a national food security strategy,” the IIED researchers noted. “Yet the evidence for this is highly questionable.”

When I read these articles, I was intrigued but also puzzled. Many of the statements were simply wrong. For example, rice was not of minor importance in Mozambique. According to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), “rice is considered a strategic crop in Mozambique, where it is expected to contribute to ensuring food security in the country.” In 2007, according to FAO statistics, Mozambique—one of the world’s poorest countries—had paid over $145 million to import nearly 500,000 metric tons of rice.

It was also not true that Mozambique had made the Chinese language compulsory at any level of schooling. The stories had other errors. For example, in 2006 Beijing had offered to allow duty-free entry for 400 products from Africa’s least developed countries (including Mozambique), but fewer than 10 percent of the products were agricultural. The list included knitted bow ties, ballpoint pens, and leather jackets. Rice, a highly protected crop in China, was decidedly not on the list.

Although the Chinese had expressed strong interest in funding the massive dam at Mpanda Nkua (as long as a Chinese company carried out the work), they had never provided a loan. The author was also clearly not aware that Chinese agribusiness companies had already been investing in agriculture in Mozambique—and other parts of Africa—for over two decades.

These details could be easily checked, and this level of carelessness raised questions about the other claims. There were no references to interviews or fieldwork in Mozambique, or to primary sources that could confirm the more sensational allegations: a massive $800 million Chinese government pledge to modernize Mozambique’s rice sector; an agreement to import tens of thousands of Chinese settlers; public protests, expressions of outrage, or government denials of such a plan.

And so I resolved to visit Mozambique. There, a different story began to take shape, one we will return to at various points throughout this book. It is a story of China’s emerging global business ambitions and an African government’s active concern with food security in a context of weak institutions. It involves not just China but also many other players: Portugal and Brazil, for example. As we will see in chapter 3, the Chinese role in this story begins not in 2006, but decades earlier. This history shaped the present engagement.

“We can’t confirm this story”

I arrived in Mozambique’s faded colonial capital for the first time in June 2009 and was immediately charmed. Maputo was quite unlike the West African cities of Lagos, Freetown, and Monrovia where I had done extensive fieldwork. The warm Indian Ocean washes against the curved beaches that fringe the edges of the city. Acacia, purple jacaranda, and royal palms line its wide avenues, although its crumbling sidewalks covered with a lacework of sand present a hazard to pedestrians. Some prominent buildings are in ruins, cratered with bullet holes, trees branching through arched courtyards.

The bullet holes are a reminder of Mozambique’s violent recent history. In 1962, a group of Mozambicans in exile in Tanzania formed the Mozambique Liberation Front, known by its Portuguese acronym Frelimo. Within two years, the Portuguese colonial government found itself fighting armed guerrillas that attacked and then melted into the mountains and jungles.

For most of the next 30 years, Mozambique would be consumed by war: its own liberation struggle, and then a protracted civil war between Frelimo, and a rival group, the Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo), backed by white-ruled South Africa. The Portuguese would be gone by 1975—the year their own revolution ended decades of dictatorship. But nearly a million Mozambicans would die before South Africa’s political transition in the early 1990s brought an end to their conflict.

Under the Portuguese, Mozambicans had acquired a strong taste for rice. Satellite images of Mozambique’s major rivers clearly show the ghosts of Portuguese canals marking out rectangular plots of land—drainage and irrigation systems built with chibalo (forced labor) starting in the late 1930s. The Portuguese fostered settler agriculture and also disrupted the subsistence practices of local farmers, compelling them to cultivate rice for delivery at low prices to privately owned mills, by threats of beatings and fines. The practice of chibalo and the coercive cultivation of rice ended only in the early 1960s. By then, dozens of Portuguese settler farms in areas like the Lower Limpopo had transformed parts of Mozambique into a bread- basket, producing over 10,000 tons of milled rice per year.13

As Mozambicans began moving to the cities, the demand for foods like rice accelerated. Local rice yields were extremely low, averaging just over one ton per hectare, compared with over six in China. Yet, as a 2005 study of Mozambique’s rice industry funded by the Italian aid agency, Cooperazione Italiana, noted, “The government of Mozambique sees significant potential to reverse this situation and ultimately produce a surplus of rice to sell both regionally and internationally.”

To become an international rice powerhouse, Mozambique would require new investment on multiple fronts. For example, while paddy rice production costs were comparable to those in Thailand, Mozambique’s rice-milling costs were up to six times higher, pushing down farmers’ profits. Modern rice mills would be essential to the expansion effort. Weak agricultural research was also a critical constraint.

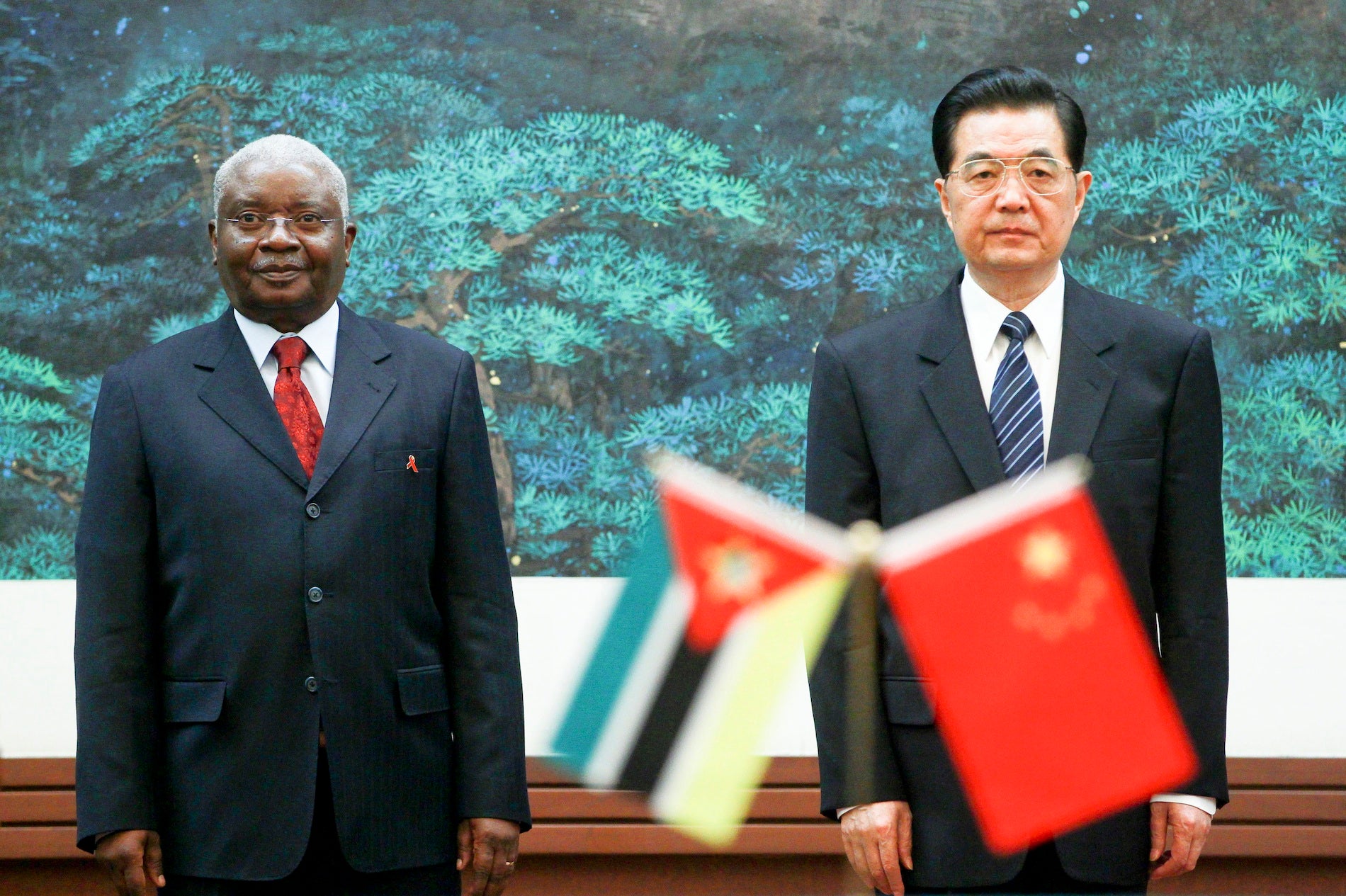

The Mozambique government identified 20 districts with high potential for rice production and stepped up their efforts to engage international partners. At the government’s request, IRRI opened an office in Mozambique. Japan, France, and Ireland provided funding to repair colonial-era irrigation works. In September 2005, President Guebuza met with Chinese President Hu Jintao at the United Nations General Assembly in New York and urged the Chinese to explore agricultural investments. Spurred by this high-level request, the Chinese commercial counselor’s office in Maputo translated Mozambique’s agricultural investment incentives into Chinese and posted them on the Chinese Ministry of Commerce website.

My first meeting in Maputo that June was with Justiça Ambiental, a local environmental activist group. I asked about the stories I had read. One of the members recalled hearing a rumor from a cooperative in the northern town of Quelimane about Chinese interest in the Zambezi valley, but they knew of no protests about plans to bring in Chinese farmers. “We can’t confirm this story,” they said.

I met with the staff in charge of agricultural assistance at the World Bank and other international aid agencies, but no one recalled hearing about a Chinese pledge to provide $800 million for rice production or any stories of public outrage or government denials of a plan to bring in Chinese settlers. At the International Monetary Fund’s Maputo office, a staff member who had been tracking Chinese investment in Mozambique told me, “Agriculture is a priority area for the Mozambique government. A group of prominent Frelimo people want to find investors for the Zambezi valley. They have offered special tax incentives. There is Chinese interest, but nothing firm.”

This story was consistent with a March 2006 notice in Chinese on the website of the Chinese economic counselor’s office in Maputo: “In recent years, our office has received a number of agricultural cooperation requests. The Zambezi River Basin Development Office has invited Chinese cooperation in growing cotton and rice.”

At the Ministry of Agriculture, a group of officials in the office of the permanent secretary, Daniel Clemente, told me: “We approached the Chinese to support our agricultural development.” The China Export Import Bank was providing a line of credit of $50 million to finance machinery imports and the construction of three Zambezi valley factories for processing cotton, corn, and rice. The Chinese government was also funding an agricultural research demonstration and training center near Maputo with a grant of about $6 million. “This is less than we had expected,” the Mozambican officials added. I asked if they had been expecting $800 million. They laughed, shaking their heads, no. “Where does this figure come from?”

I worked with several students to search Portuguese-language sources, including archives of the local independent newspapers. We found no media reports of an $800 million Chinese investment pledge, no stories of any intergovernmental agreement to bring in Chinese settlers, and no accounts of protests or outrage leading to the cancellation of any planned Chinese farming project. In dozens of interviews, I failed to find anyone who had even heard of these central pillars of the story. The narrative sketched shimmered like a mirage, until it slowly began to fade away.

In the office of Savanna, Mozambique’s leading independent weekly newspaper, an alternative story began to take shape. There, I was reminded that Portugal had returned its former colony of Macau to China in 1999, where it had the same kind of autonomy given to Hong Kong. I learned that Stanley Ho, the billionaire Macau gambling magnate, had an interest in Mozambique. In 2005, Stanley Ho’s investment company, Geocapital, had joined forces with several wealthy Mozambicans, setting up a local investment company called Zamcorp. “Zamcorp has $500 million worth of plans and projects for the Zambezi valley,” an editor told me. “They have been trying to bring in Chinese investors.”

“What about Chinese farmers?” I asked. He laughed but then leaned forward and said, “Some Mozambican businessmen connected to Zamcorp have said privately that we should import Chinese workers to transform the Zambezi valley. These are business people. They would like Mozambique to have less restrictive labor laws. For example, they would like to be able to bring in Indian accountants. Local accountants here can get $4,000 to $5,000 a month! But there was no decision to do this.”

In 2010, Swedish-Norwegian researcher Sigrid-Marianella Stensrud Ekman, who speaks Chinese and Portuguese, came to Mozambique to dig more deeply into the same story. Her findings paralleled mine (we later wrote an article together for African Affairs). In particular, Ekman challenged the idea that “China” had been demanding large land leases in the Zambezi valley. Instead, the government’s Zambezi River Basin Development Office “tried hard to get Chinese investment and failed.”

Portuguese scholar Ana Cristina Alves elaborated on the strong Portuguese connection missing from the original story. The shareholders in Stanley Ho’s Geocapital included Portuguese political and business elites such as Almeida Santos (former president of Portugal’s parliament) and Jorge Ferro Ribeiro (former Minister for International Cooperation in Lisbon). By setting up Zamcorp, Alves argued, the private investors hoped to promote the valley’s development “through privileged access to Chinese capital.” Yet Zamcorp had been unable to develop a single project. Their efforts to pull Chinese investment into the Zambezi valley failed, Alves suggested, because they lacked “formal linkages to the Chinese state.”

Clearly, there had been Chinese interest in the Zambezi valley. Yet as the Chinese economic counselor in Maputo would later tell me: “The Mozambique government thinks the Zambezi valley is the best place for agriculture, but it is far from Maputo, from the port, there are problems with transport.” His assessment was reflected in a report from Sérgio Chichava, a researcher at the Maputo-based Institute of Social and Economic Studies. Chichava found that in 2010 the Zambezi River Basin Development Office worked with a Chinese group that had asked them to put together a 50,000-hectare concession. However, after conducting a feasibility study, the Chinese investors decided that the lack of infrastructure and problems with water made the Zambezi region too expensive.

As this suggests, had a Chinese company wanted to obtain a major concession of land in the Zambezi valley, they would likely have had little problem doing so. Indeed, an Oakland Institute study showed that between 2004 and 2009 Mozambique granted over one million hectares to foreign investors, mainly from Europe and South Africa; Chinese investors were conspicuous only by their absence. Instead of a one-dimensional China aggressively seeking land to settle tens of thousands of Chinese farmers in Mozambique, what I found was an active group of Mozambican and Portuguese elites trying to position themselves to reap what they hoped and expected would be a bonanza of Chinese investment.

Meanwhile, far from the Zambezi valley, a new Chinese project was taking root. In December 2005, China’s Hubei Province Department of Commerce led a study tour to Zambia, Kenya, and Mozambique. Since the 1970s, the state farm system in Hubei, one of China’s main grain-producing regions, had been sending multiple teams of agriculture experts to Africa under China’s aid program. (In 2007, while doing fieldwork in Sierra Leone, I met several of their experts in the small town of Bo, working with Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Agriculture on rice cultivation.)

When the Hubei delegation reached Mozambique, they visited Gaza province and the former Portuguese irrigation system near the town of Xai-Xai in the Lower Limpopo valley. The Gaza provincial govern- ment offered them 300 hectares to start a demonstration farm and transfer technology to local farmers. The delegation brought back samples of the soft, black soil for testing; the quality was excellent. In 2006, Hubei province signed a twinning agreement with Gaza province and asked the provincial bureau in charge of oversight for Hubei’s 53 state-owned farms to set up a company.

The bureau brought together a set of 19 investors from some of Hubei’s state-owned farms to establish a company called Hubei Lianfeng (United Harvest). The new farm, formally established in May 2007, would be called Gaza-Hubei Friendship Farm. Hubei Lianfeng was also tasked by the Chinese aid program to build a $6 million agro-technology demonstration center (ATDC) for Mozambique, just outside Maputo. “Hubei’s project fits very well with Mozambique’s national five-year plan,” the Mozambican ambassador told a reporter from the Yangtze Daily News, in June 2007. The team described plans to produce rice, but also flowers, and perhaps high value-added fruits and vegetables for direct shipment to Europe.

Surprisingly, despite all this activity, Hubei province’s very real investment project was not mentioned in the articles published on the Swiss and CSIS websites.

Excerpted from Will Africa Feed China by Deborah Brautigam. Copyright © Oxford University Press 2015. Excerpted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or reprinted without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press.