How Côte d’Ivoire’s president used an old autocrat’s playbook to turn his country around

Seeing the economic vitality in Côte d’Ivoire, you could almost forget that this country was ever embroiled in a vicious conflict with undercurrents of xenophobia and ethnic hate. Yet when Alassane Ouattara—the runaway favorite to win a second term in this coming weekend’s presidential election—took office in May 2011, it was after five months of post-election violence in which 3,000 people had died, and Côte d’Ivoire was still suffering the aftermath of its 2002-03 civil war. Ouattara took over a country awash in weapons and seething with recrimination.

Seeing the economic vitality in Côte d’Ivoire, you could almost forget that this country was ever embroiled in a vicious conflict with undercurrents of xenophobia and ethnic hate. Yet when Alassane Ouattara—the runaway favorite to win a second term in this coming weekend’s presidential election—took office in May 2011, it was after five months of post-election violence in which 3,000 people had died, and Côte d’Ivoire was still suffering the aftermath of its 2002-03 civil war. Ouattara took over a country awash in weapons and seething with recrimination.

Since then, four years of GDP growth above 8%, a foreign investment surge, a real-estate boom, and an aggressive program of roads, bridges, and power projects convey how much things have changed. So how did Côte d’Ivoire settle down so quickly?

The economy helped. So did the fact that much of the population was tired of conflict. But a key factor has been that Ouattara, a former IMF technocrat known for economic chops, has also shown exceptional political skill. He has neutered the opposition, held together his own fractious camp, and cemented public support like an expert.

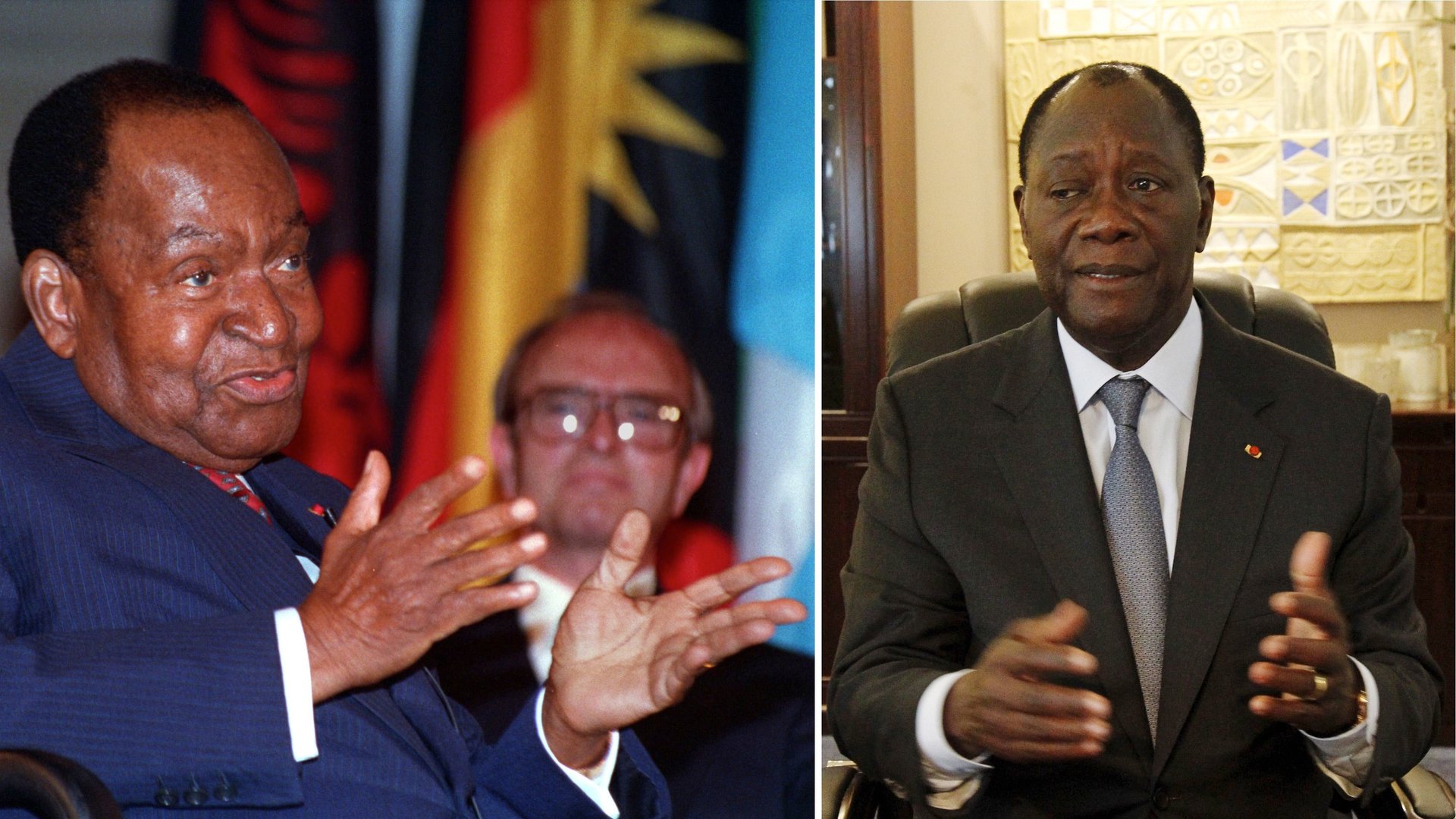

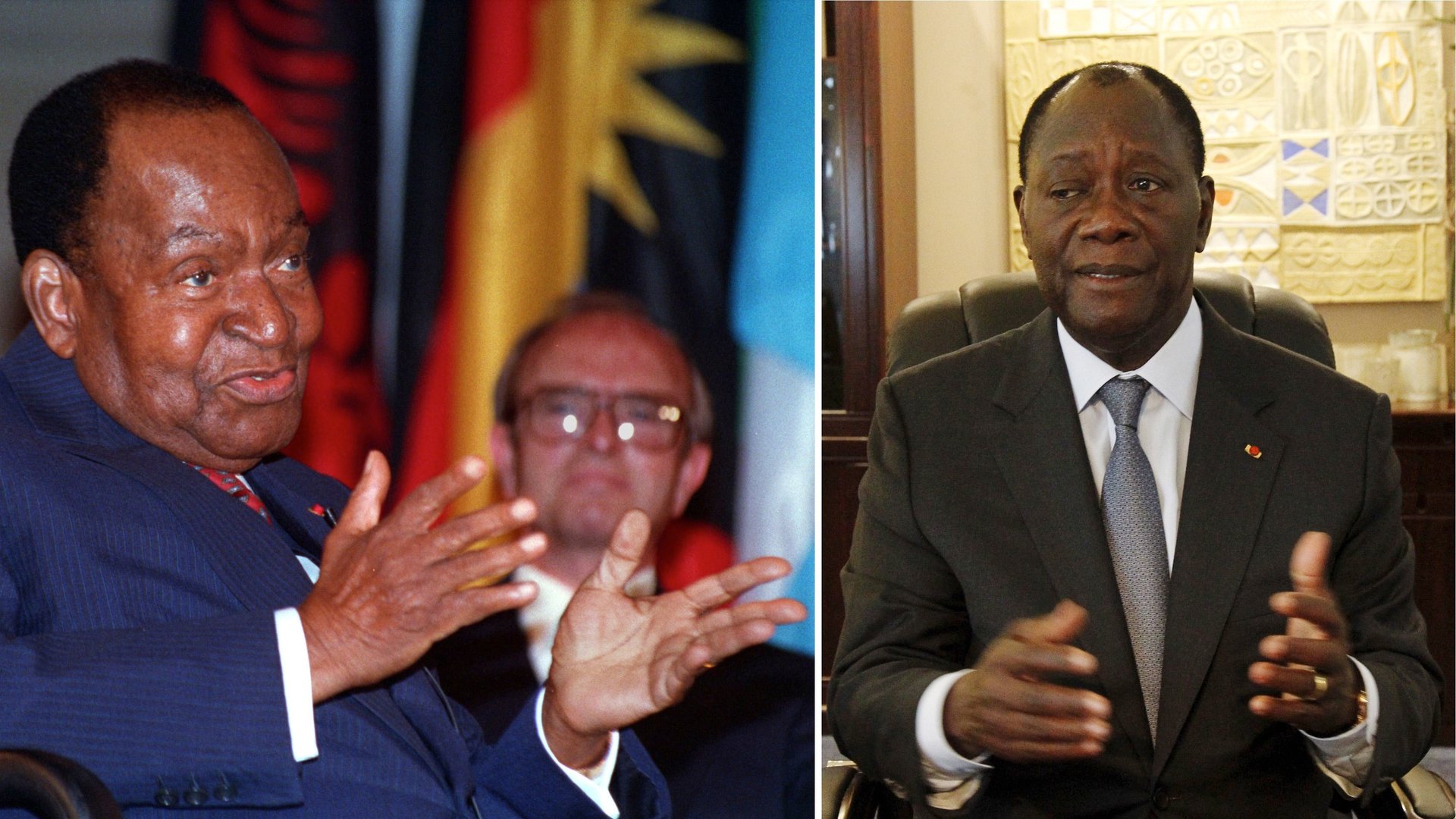

And connoisseurs recognize his playbook: It comes from the master, Félix Houphouët-Boigny (on the left in the image above), who ruled the country from independence in 1960 to his death in 1993, with Ouattara as prime minister for the final three years.

Houphouët was an autocrat, but not quite a dictator. Though he didn’t allow multi-party elections until 1990, his Parti Démocratique de la Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI) held internal primaries. He made sure that high offices—and thus patronage opportunities—were spread across regions and communities. He cultivated “dialogue” and “pardon,” bringing chastened opponents back into the fold after a few years. A pragmatist, he kept close ties with France, and welcomed immigrants from Burkina Faso to build the Ivorian economy. He kept farm incomes high—at least until commodities collapsed in the 1980s—and invested in infrastructure. At his death, Côte d’Ivoire had West Africa’s best roads and electricity.

It worked well enough then, and now Ouattara is reviving Houphouët’s principles. He has conducted grand “state visits” around the country, holding cabinet meetings in provincial towns, shaming state agencies and private contractors into speeding service delivery, and prompting rituals of allegiance from local dignitaries. The technique is pure Houphouët: For years the old president rotated the celebration of the national holiday around the country, each time bringing roads and rural electrification to the chosen region.

Like Houphouët too, Ouattara has been expert at co-opting rivals. The party of his ousted predecessor, Laurent Gbago, has split between hardliners who are boycotting the election and moderates who are running a candidate, Pascal Affi N’Guessan. The moderates have cut deals with the government, and seen assets unfrozen and court cases evaporate.

But Ouattara’s masterstroke has been his embrace of Henri Konan Bédié, who succeeded Houphouët as president (1993-99) and is now head of the PDCI. The two once hated each other; it was under Bédié that the xenophobic doctrine of ivoirité emerged, aimed at discrediting Ouattara on the grounds that his father may have come from Burkina Faso. Now, Ouattara has killed Bédié with kindness—deferring to him as his elder, even naming the fancy new lagoon bridge in Abidjan after “HKB.” In return, Bédié has thrown the PDCI’s support behind Ouattara, clearing the field.

What Houphouët did poorly was prepare his succession. Ouattara has that to deal with too: He will be 78 in 2020 and does not intend to seek a third term. His camp is full of ambitious people—patronage barons, technocrats, ex-rebels—and the opposition will regroup. Even before he secures his second term, Ouattara must already be thinking of how to make sure Côte d’Ivoire stays stable and prosperous after it ends.