Why Kagame’s bid to serve a third term makes sense for Rwanda

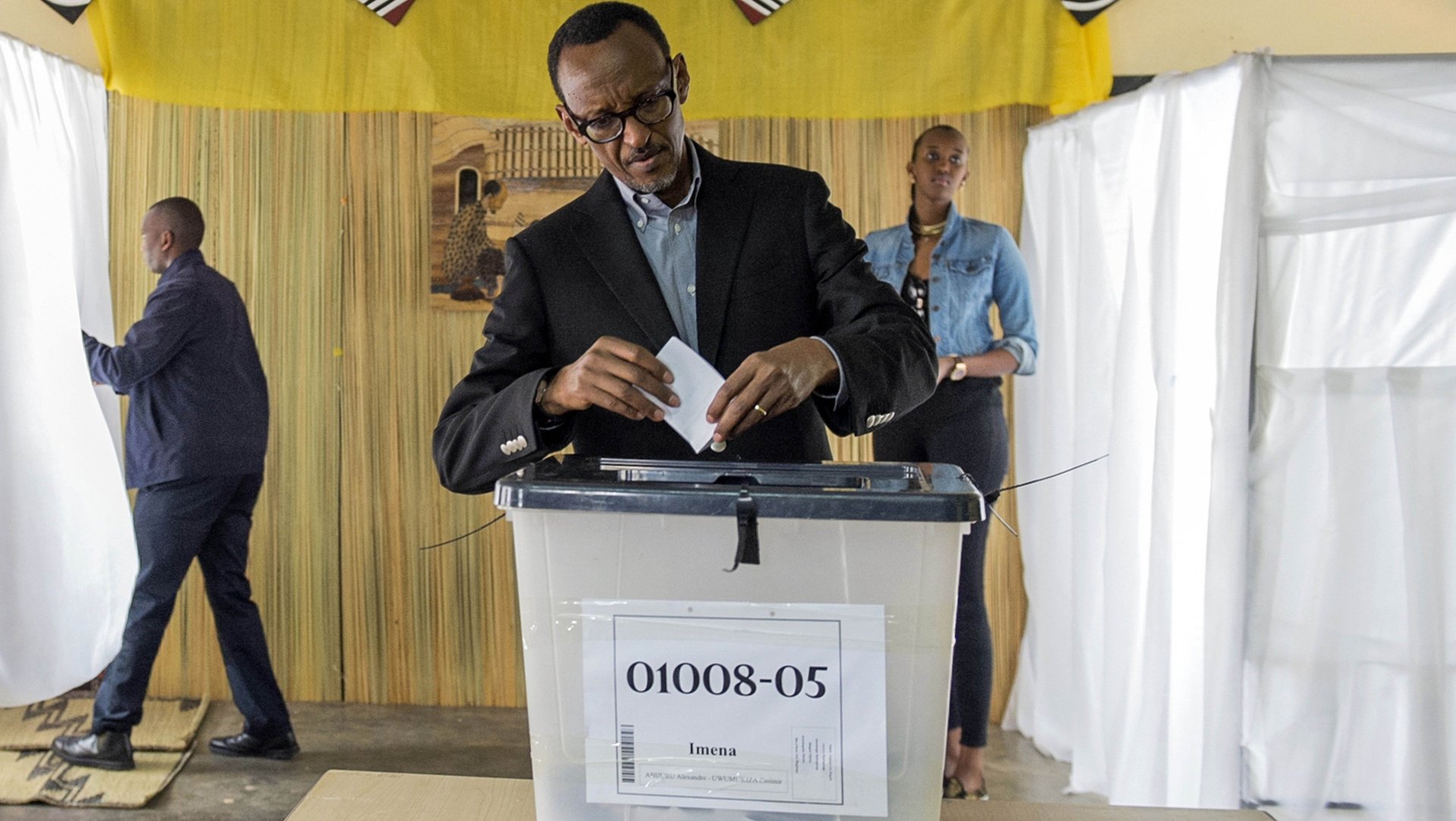

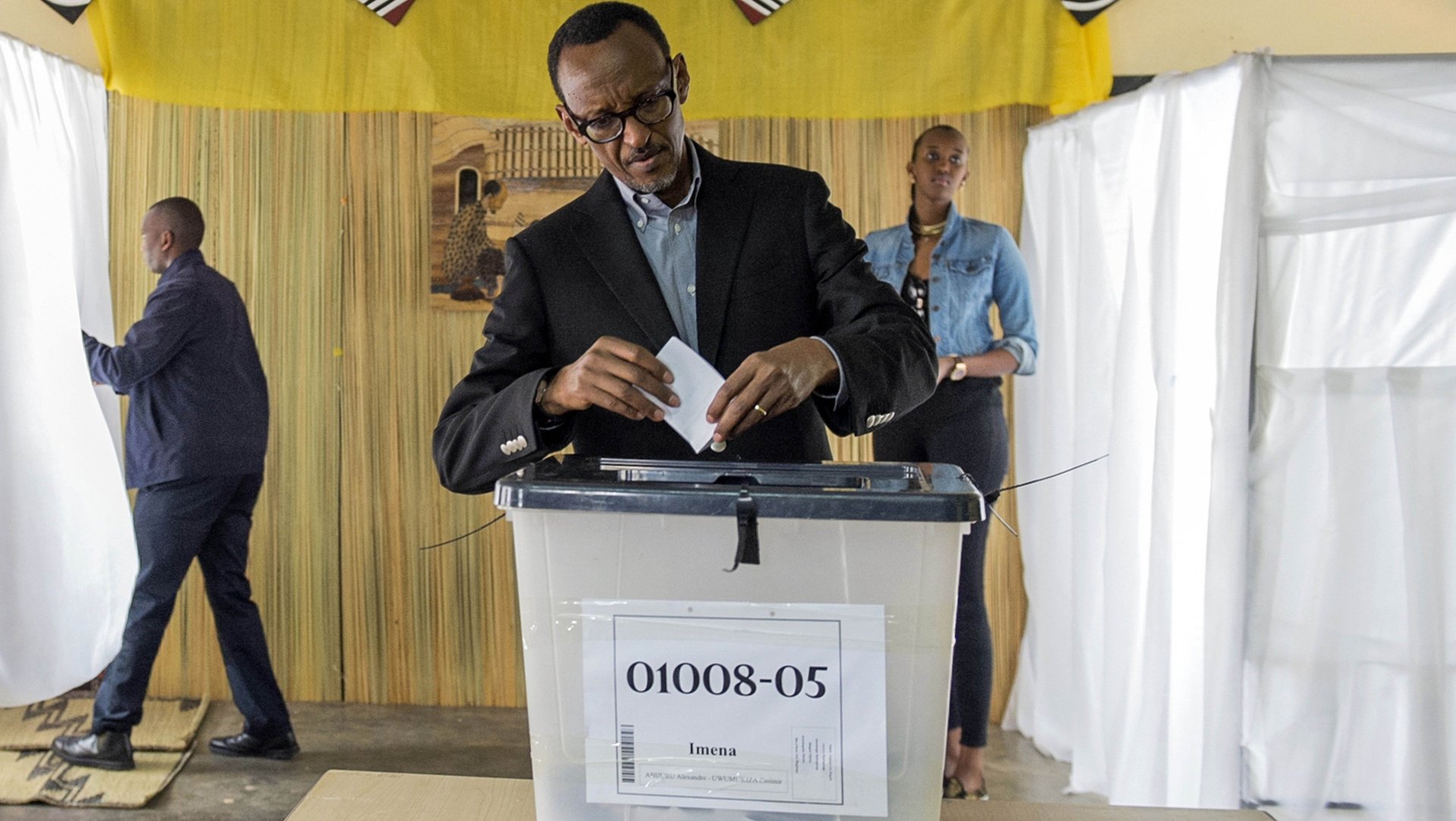

Rwandan president Paul Kagame recently confirmed that he will seek a third term in 2017 after more than 98% of Rwandans voted in a referendum to lift the presidential term limit.

Rwandan president Paul Kagame recently confirmed that he will seek a third term in 2017 after more than 98% of Rwandans voted in a referendum to lift the presidential term limit.

Kagame’s decision not to step down has prompted a barrage of criticism. Western governments, media outlets and human rights groups have painted him with the same brush as other central African “strongmen”.

Attempts to extend presidential terms by Blaise Compaore of Burkina Faso and Pierre Nkurunziza of Burundi have led to instability and violence in these nations.

Other leaders in the region—such as Denis Sassou Nguesso of Congo-Brassaville and Joseph Kabila of Congo-Kinshasa—are also considering changes to allow third-term extensions.

But Rwanda’s situation is unique. Unlike the third-term fever afflicting other countries in the region, Rwanda is not mired in corruption and economic stagnation.

During the past decade its economic growth has averaged around 7% per year, maternal and child mortality has fallen by more than 60% and near universal health insurance has been achieved. The country is also now considered one of the safest and least corrupt in sub-Saharan Africa. And in just the past three years, the percentage of people living in poverty has dropped from 44.9% in 2011 to 39.1% in 2014.

This remarkable list of achievements is attributed to the leadership of Kagame, who assumed the presidency in 2000.

Kagame’s agenda

Despite these accolades, Kagame is frequently criticised by human rights groups over Rwanda’s tightly controlled political space.

He has sought to place a strong emphasis on developing a new Rwandan national identity. He has done this in an attempt to sever connections to the primordial categories of ethnic identification that provoked the tragic events of 1994. Ethnic politics and discrimination have thus been outlawed in the country.

With the genocide against the Tutsi still in recent memory, Kagame has committed to power-sharing only among parties that are firmly aligned against a revival of ethnic sectarianism. Within this political settlement, it is the pursuit of development — not negotiation — that is seen as the principal path to national reconciliation.

Understandably, this strategy is based on the fear that a more adversarial style of policy-making and debate — one that could fulfil the West’s more exacting standards of democratic participation — would give voice to extremists.

This foremost includes the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, the eastern Congo-based rebel group led by former genocidaires. Indeed, it was largely multilateral Western agencies that thrust multiparty democratic institutions onto Rwanda in the early 1990s. This, it could be argued, provided a platform for extremist views held in the country.

Kagame has always claimed that Rwandans would decide on what they want to become. Not the UK, US or any other nation. Many Rwandans were fearful and anxious about what might happen after 2017. For them, Kagame is seen as a stabilising force for the country and its best chance for continued socio-economic progress.

His supporters have embraced his third term to ensure he is able to finish some important projects, recognising that such a capable leader is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They see Rwanda as following the lead of successful late industrialisers like Singapore, where significant socio-economic progress was achieved under the long-term leadership of Lee Kuan Yew.

Why striking a balance is important

Where a society is ethnically divided, it is difficult to ignore the need to strike a balance between the protection of the wider minority interests and the power of the central state authority.

It is clear that Rwandans require a constitution that can accommodate their fears of ethnic divisions, persecution and impunity. They also require one that would consolidate the socio-economic gains made thus far. Certainly, a path Rwanda would not want to follow is that of Kenya, where an ethnopolitical calculus plays out each election cycle and reinforces deep ethnic divisions.

For Kagame’s supporters, the controversy over a third term is a preoccupation of Western observers, not Rwandans. The terms of the debate, they argue, should instead focus on what the leader has already achieved for the country—the evidence of which is unequivocal for Kagame—and what his vision is for the future.

It takes time for any society to recover from conflict, especially a genocide. Two decades ago, Rwanda was a failed state. Kagame himself commanded the rebel force that ended the genocide. But the violence had decimated people and infrastructure.

Kagame then placed national reconciliation at the top of the political agenda, instead of ethnic exclusion. Under his stewardship, Rwandans have been given a taste of what peace, stability and development feel like—regardless of ethnicity.

For the people of Rwanda, Kagame’s record inspires trust in an otherwise uncertain future. For this reason, he may be the only person who can hold the country together. His vision to turn Rwanda into a middle-income country is on track. And it is a boat that most Rwandans do not want to rock.

Given the contextual and developmental realities faced by Rwanda, Western concerns over two, three, four, or more presidential terms appear obtuse. What matters for Rwandans is progress, stability, quality of life, good governance, and capable leadership. In short, when it comes to Rwanda, the West may not know best.

Thomas Stubbs, Research associate, University of Cambridge

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.