A Zimbabwean architect builds for the “forgotten economy” by letting people design for themselves

When Zimbabwean architect Maxwell Mutanda set out to make life easier for street hawkers in his hometown of Harare, he realized his guidance wasn’t all that needed. ”We thought, ‘Okay let’s design for them.’ But as we entered that space we realized that they usually design for themselves,” Mutanda says.

When Zimbabwean architect Maxwell Mutanda set out to make life easier for street hawkers in his hometown of Harare, he realized his guidance wasn’t all that needed. ”We thought, ‘Okay let’s design for them.’ But as we entered that space we realized that they usually design for themselves,” Mutanda says.

Zimbabwe’s street vendors are creative, selling everything from phone cards to four poster beds and tombstones. They operate from roadside stalls, the boot of their cars, or in between cars stuck in traffic—but they lack basic necessities like access to water, clean toilets, or electricity.

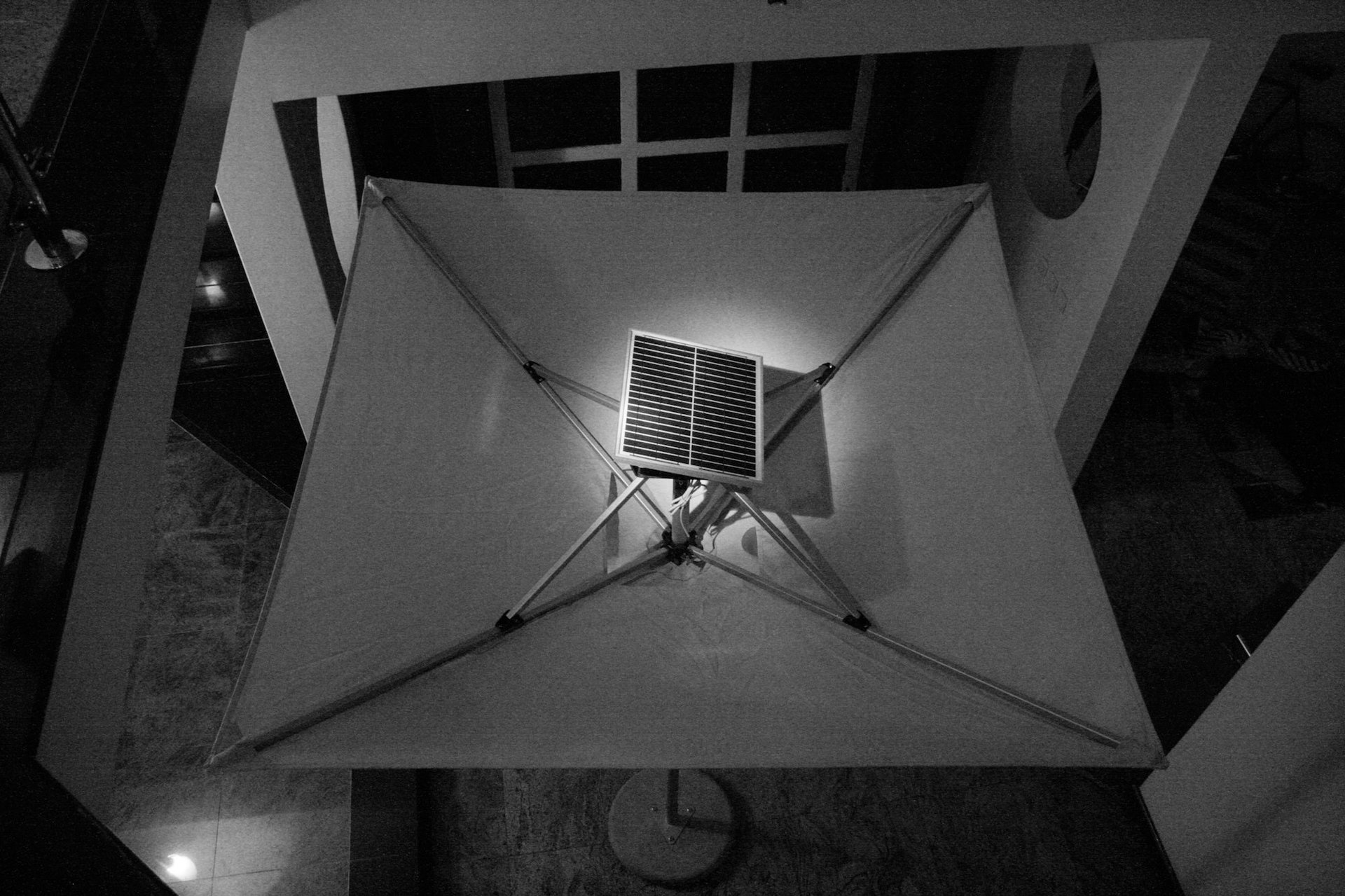

With that in mind, Mutanda and his partner Safia Qureshi at Studio [D] Tale, based in London, came up with a “menu of options” for sellers to choose from and adapt as needed. Vendor stalls, often slapped together using cheap slabs of wood, could now be upgraded with pallet flooring, composting toilets, umbrellas that purify rainwater as well as capture solar energy, and display shelves for their wares.

So far, the project has kitted out five street vendors, with most of them opting for simple things like the shelves and the umbrellas. The studio hopes to introduce the modifications to more sellers.

The idea behind the project, first started in 2014, is to improve the built environment—the infrastructure and resources available— for those in the “forgotten” or informal economy, according to Mutanda. Like many countries on the continent, street vendors and others involved in informal trade account for at least 60% of Zimbabwe’s economy.

More broadly, Mutanda’s project echoes a philosophy that architects working in Africa are increasingly turning to—that design should build on the resourcefulness and life hacks that communities have long relied on.

Another project, the “Empower Shack,” employs this principle in a South African township where residents in informal settlements have been cobbling together their own homes for years.

Urban Think Tank, a design practice in Venezuela, Ikhayalami Development Services, a South African NGO, and other partners have developed a prototype of a two-story home that residents can expand to include a third story. Made with concrete and other more permanent structures, these houses are adaptable, but also fire resistant and offer better sanitation and privacy than the traditional township home. A total of 90 “Empower shacks” will be built in Khayelitsha in Cape Town, the country’s second largest township, according to Urban Think Tank.

Building on existing resourcefulness also means borrowing ideas from elsewhere. Inspired by space-strapped Catholic churches in the Philippines that have begun holding mass in empty shopping malls, Mutanda says his studio is also looking into how to design for the “pop-up church.”

One potential focus are the pilgrims who journey to one of South Africa’s largest churches, the Zion Christian Church in Moria, every year for Easter. More than 5 million visitors flood the city, camping out in tents or their cars in order to be there for the weekend, according to Mutanda.

“It’s really embedded in the culture on the continent that people create spaces for themselves,” Mutanda says. “It’s something that is being done by people who aren’t designers… like the slums in Kibera [in Nairobi] or the favelas in Brazil. They actively designed their lives. No one told them to do it.”