Cancer is on the rise in Africa just as some of the few radiotherapy centers fall apart

Over the past two months, Carol Atuhirwe has become the face of Uganda’s broken cancer treatment facilities. The 29-year-old, was diagnosed with throat cancer five years ago, and has spent the years in and out of the country’s only cancer treatment facility. You could say she has received aggressive treatment for the disease. She says she has had 36 surgeries. Her blog documents many rounds radiation and chemotherapy. The radiotherapy left her right shoulder and neck burnt. That was before the radiation machine itself completely broke down in mid-April, breaking news that sparked public outrage throughout the East African country.

Over the past two months, Carol Atuhirwe has become the face of Uganda’s broken cancer treatment facilities. The 29-year-old, was diagnosed with throat cancer five years ago, and has spent the years in and out of the country’s only cancer treatment facility. You could say she has received aggressive treatment for the disease. She says she has had 36 surgeries. Her blog documents many rounds radiation and chemotherapy. The radiotherapy left her right shoulder and neck burnt. That was before the radiation machine itself completely broke down in mid-April, breaking news that sparked public outrage throughout the East African country.

“The machine broke down, yes. It was old. It should have been replaced much earlier,” Chris Baryomunsi, the country’s deputy health minister, tells Quartz. He says, that while it was the only one of its kind, an external beam radiotherapy machine, the country owns two other functional radiotherapy machines of the brachytherapy kind. External beam radiotherapy machines treat patients for whom radiation has to be administered from outside the body. Brachytherapy machines treat those for whom the radiative material has to be inserted into the body.

The machine that burnt Atuhirwe’s skin was the old, now dead, Cobalt 60 external beam machine. It had been installed in 2002 and should have been decommissioned after 10 years. A 2013 inspection by Uganda’s Atomic Energy Council found the machine was exposing patients to direct radiation but the cancer institute continued using it. Atuhirwe needs reconstructive surgery for the extensive radiation burns. In addition, her trachea got displaced following one of the surgeries. She now eats through a tube and is no longer able to speak.

The state of cancer treatment in Uganda symbolizes a continental problem. The health systems of most African countries are not equipped to treat diseases like cancer. For decades, the continent struggled with communicable diseases like malaria and HIV/AIDS. Doctors were trained to respond to these. Hospital facilities were skewed to contain these epidemics. Now, when the World Health Organisation is warning that non-communicable diseases are sharply rising ( as Africans become wealthier), the continent isn’t well prepared for the double disease burden.

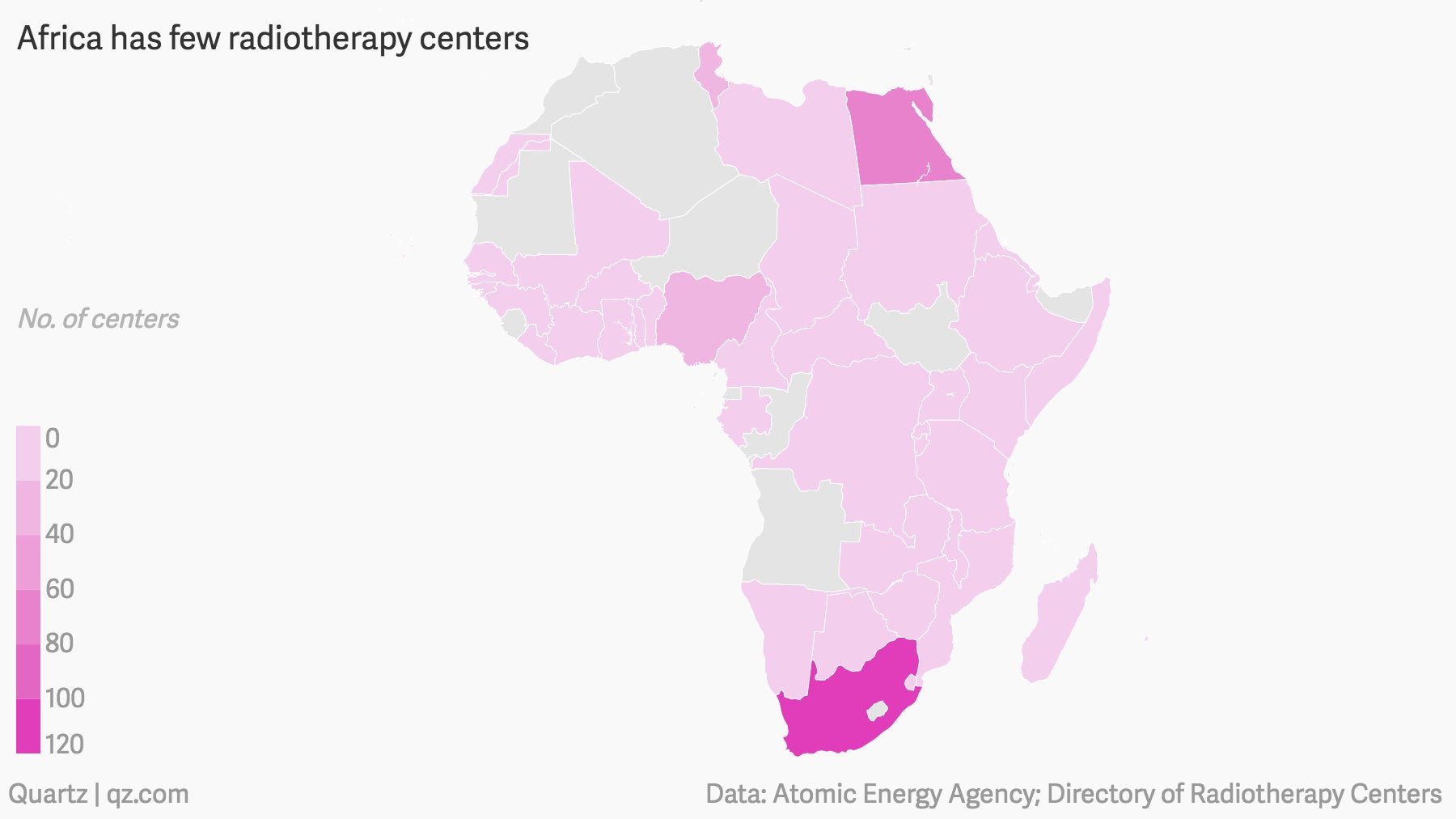

More than 20 countries on the continent don’t have even a single facility with working radiotherapy machines, even though about 63% of cancer patients need radiation. Even in countries that a machine or two, “it is a really sorry state of affairs when you look at the cancer load patients they have,” says Professor Niloy Datta, an oncologist who has worked as a consultant of the Atomic Energy Agency (AEA). He has travelled through middle and low income countries, surveying their radiotherapy needs on behalf of the AEA.

“Uganda has one radiotherapy treatment unit. Tanzania has two. Namibia has two but it is better than others because it has a low cancer load because of its low population.” There are 385 radiotherapy machines on the continent of 54 countries and 1 billion people. About 60% of the machines are found in just three countries: South Africa, Egypt and Morocco. The next 20% are also in just three countries: Tunisia, Nigeria and Algeria.

Given the poor state of treatment facilities, Africa has the highest death rate among cancer patients even though it still registers a lower number of cases compared than most parts of the world. Data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, a program of the World Health Organisation shows 71% of the people diagnosed with cancer in Africa die.

Yet, the number of cancer cases themselves are going to get only bigger. Datta, quoting WHO predictions, says that even though communicable diseases still dominate by 2020, it will be a nearly half and half split with non-communicable ones. “One fifth of the deaths from non-communicable diseases are going to be from cancer,” he says.

African public health officials like Baryomunsi are aware of this. “The disease burden is now a mixed picture,” the Ugandan health minister agrees. He says the country has as a result increased funding to its lone cancer treatment facility from around $600,000 a year five years ago to about $13 million currently. In 2015, the country got a $22 million loan from the African Development Bank to upgrade the facility, known as Uganda Cancer Institute, to what Baryomunsi calls, “a regional center of excellence.”

However, professor Datta could not be less impressed with this approach. “It is very easy for politicians to throw around big words for headlines. You don’t start with a regional center of excellence,” he retorts. Having seen the Uganda Cancer Institute, Datta doubts that it could be turned into a center of excellence even in 10 years. “Forget it. What we need are units closer to the patients’ homes. Travel in Africa is difficult. I am talking about centers that work as primary units linked to secondary centers which are connected to mentoring centers.”

As he sees it, African governments need to distribute access to cancer treatment rather than sink millions of dollars into centralized units. Even then, the AEA estimates that a small radiotherapy unit that would treat 500 to 800 patients a year costs about $5 million to set up and the machine would need to be replaced in 15 years.

In the meantime, patients grapple with the inadequate system, often falling through its cracks. Atuhirwe’s friends circulated a

video asking for funds to send her to the U.S for treatment. Outraged about the broken machine, members of the public responded with gusto. They sent mobile money contributions to her phone number. Supermarkets placed ‘Save Carol’ baskets at entrances for shoppers to drop contributions. School alumni associations pitched in. In some places, people donated cows for cash. Selfies behind a pink cut-out frame labelled #SaveCarol, #FightCancer, spread across Ugandan social media timelines.

In at least three Ugandan towns, charity car washes were held. Muhereza Kyamutetera, a communication strategist organized the largest car wash fundraiser in the capital city, Kampala on April 27th. “We washed 420 cars including a [road] grader,” he says of the event, from which over $16,000 was raised. A total $98,600 was raised from all the fundraising activities. But, it all may have come too late for Atuhirwe.

Last week, her doctors (both in Uganda and the US), ruled her too ill to travel. She is back to receiving indefinite palliative care at the Uganda Cancer Institute. Like so many other patients in Africa, she is bleakly stuck within a broken system.