Africa’s economies are set to get a boost from tighter integration with or without Brexit

The African Union (AU) is holding its 27th summit in Kigali, Rwanda this week in the wake of the United Kingdom’s referendum decision to withdraw from the European Union. The outcome of last month’s referendum has sent seismic waves across Africa. Many observers have focused on the negative short-term damage to African economies.

The African Union (AU) is holding its 27th summit in Kigali, Rwanda this week in the wake of the United Kingdom’s referendum decision to withdraw from the European Union. The outcome of last month’s referendum has sent seismic waves across Africa. Many observers have focused on the negative short-term damage to African economies.

Others, however, suggest that Brexit is likely to unravel the African Union (AU). Even more extreme is the view that the AU should be dissolved because the continent has mindlessly mimicked western institutions.

These claims are as devoid of sound reasoning as they are historically unfounded. It is true that there are some analogies between the EU and the African Union. However, Africa’s regional integration is designed specifically to avoid the pitfalls of Brexit-like scenarios.

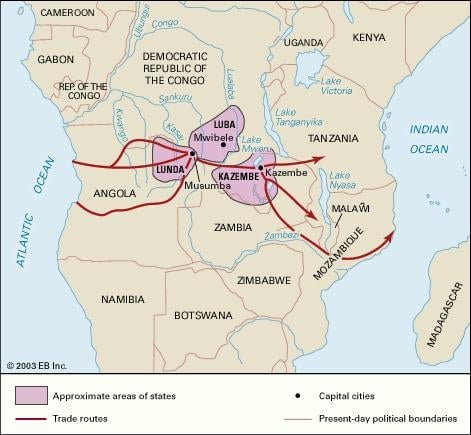

First, Africa has a much longer history of regional economic integration than Europe, some of which goes back to the colonial period. Africa’s first tripartite trade arrangement was the Luba-Lunda-Kazembe network that thrived between 15th and 19th centuries. It spanned central Africa and connected the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

Africa has also known and managed Brexit-like events. East African nations created a post-independence federation comprising of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. The European Economic Community in its early days endeavored to learn lessons from its successes. It collapsed in 1977 and was revised in 2000 as the East African Community (EAC) with new objectives adjusted to suit contemporary realities.

Those arguing that Africa’s fate is tied to European experiences have it backward. It is Europe that might in fact learn some lessons from Africa’s longer history of regional integration. The EU was founded on a negative agenda of seeking to prevent another war. It was a containment measure that was gradually adjusted to achieve other objectives.

Africa’s regional integration efforts have been shaped by the positive idea of pan-Africanism that recognizes the need to build on local and national identities while strengthening continental and global networks. This is illustrated by the creation of a single electronic passport to foster movement of Africans while retaining sovereign boundaries.

Africa has learned a lot from the last few decades of economic dogma. The continent stood firm against the excesses of neoliberalism when it rained havoc on nascent nations. Despite western bullying, Africa evolved its approach to regional integration with three planks: trade liberalization, industrial development and infrastructure connectivity. Underlying the three lay a moral claim to pan-Africanism that was expressed in the ability of regional economic communities to serve as the building blocs for a continental market.

Africa has also rejected the traditional view that economies grow in a linear way from agriculture to industry to services. To the contrary, Africa has adopted a system-wide approach that builds on agriculture and radiates horizontally to include other industries. This approach is based on the humanistic view that nearly 70% of the African population derives its livelihood from agriculture..

Agricultural development through increased productivity and infrastructure that links rural areas to national, regional and global markets will remain a priority for prosperity. Additional measures needed to achieve food and nutrition security include empowering women though access to farm technologies, relevant education and secure land rights. Economic integration in Africa is an intergovernmental process, leaving the decision-making powers in the hands of governments, exercised through policy guidance bodies such as the summits and the ministerial meetings. At face value this may resemble the unaccountable EU Commission in Brussels. But in reality it is shaped by the interest of nation states.

For example, the EAC and the EU negotiated an Economic Partnership Agreement that was meant to serve as the successor to post-colonial trade agreements. However, Tanzania has decided to withdraw from the pact saying that it undermined its aspirations to build its nascent industries. The move may be interpreted as Tanzania’s cautious approach to regional integration. But fundamentally, the withdrawal demonstrates Africa’s interest to shape its global economic diplomacy through industrial development and not the traditional focus on export of raw materials.

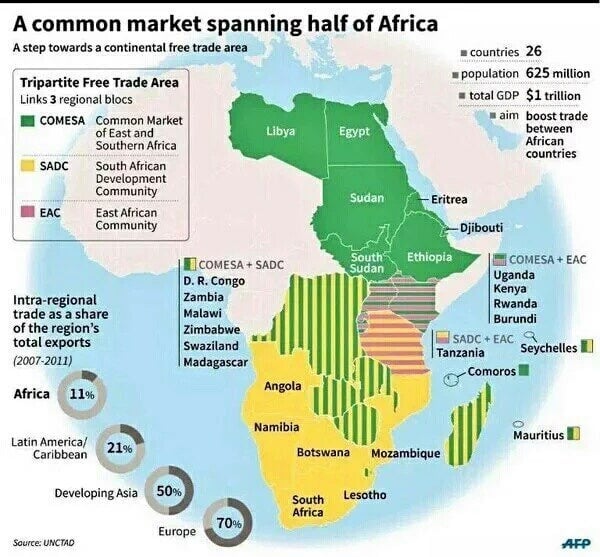

Africa’s economic integration is projected to be achieved by 2028 through a series of stages that are complemented with programs which address short-term revenue shortfalls arising from elimination of customs duties. They also include capacity building for governments and economic operators to enable them to participate effectively in regional trade and subsequently in international markets. Regional bodies such as the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) have set aside funds to support short-term adjustments by countries to long-term regional integration.

It is true that the turmoil arising from Brexit will affect African countries by virtue of their growing participation in the global economy. But doomsters are wrong to imply that this is because Africa has been aping Europe in designing its continental institutions.

Africa will continue to learn from the rest of the world as it seeks to shape its 50-year Agenda 2063 outlined by the AU. But as evidence shows, Africa is emerging as an important source of lessons on how to act locally and network globally. The continent is leading in defining a new age of glocalization.